Before World War 2 British motorcycle manufacturers enjoyed a healthy export market, selling their machines all over the world. In the USA, however, the offtake was quite small in relation to the size of the country. The reason was not too difficult to see. Although their own industry had declined rapidly soon after Henry Ford's model T went into production in 1909 to bring cheap motoring within reach of the masses, the two major US manufacturers that had survived, Indian and Harley-Davidson, still had much to offer. Their rugged vee twins had more than enough power to cope with any long distance travel, whilst in sporting events they could comfortably hold their own against any foreign-made intruders.

After the war, the picture bean to change completely, when Britain's vertical twins began to be imported. In Triumph's case, a bridgehead had been established with Johnson Motors in Pasadena, California, largely through Bill Johnson's friendship with Edward Turner. A dealer network was set up for the distribution of Triumph motorcycles by Johnson, and in no time at all the Speed Twin and particularly the Tiger 100 were attracting a great deal of interest. American enthusiasts, brought up on the big twins from Springfield and Milwaukee (and latterly from Milwaukee only) were amazed to find these attractive lightweight (to them) machines of such pleasing appearance had a surprising turn of performance. Eventually, a nationwide Triumph dealer network was set up, with Johnson Motors inc handling the western states, and Denis McCormack the eastern states through the more recently formed Triumph Corporation in Baltimore. Triumph production in Meriden was stepped up to meet the increasing demand and Turner's once seemingly optimistic US sales target of 1,000 machines a year soon became a reality.

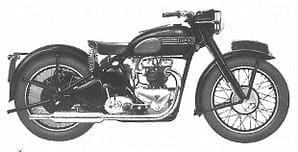

Not unexpectedly, a 500cc twin was regarded as a little on the small side by American standards, with the result that demands for even more performance began to arise. During his visits to the USA, Turner had become well acquainted with the situation and went about meeting the request in his own inimitable way. He knew he could easily increase the bore and stroke dimensions of the Speed Twin engine (63x80mm) to 71x82mm, and raise the cubic capacity to 649cc, which would give another 7bhp at 6,300rpm. Sharing the same cycle parts as the Speed Twin the oversize twin would cost little more to manufacture, yet its increased capacity would permit a greater profit margin. The Thunderbird was poised to make its debut, the first Triumph model to be made specifically with the US market in mind.

Not unexpectedly, a 500cc twin was regarded as a little on the small side by American standards, with the result that demands for even more performance began to arise. During his visits to the USA, Turner had become well acquainted with the situation and went about meeting the request in his own inimitable way. He knew he could easily increase the bore and stroke dimensions of the Speed Twin engine (63x80mm) to 71x82mm, and raise the cubic capacity to 649cc, which would give another 7bhp at 6,300rpm. Sharing the same cycle parts as the Speed Twin the oversize twin would cost little more to manufacture, yet its increased capacity would permit a greater profit margin. The Thunderbird was poised to make its debut, the first Triumph model to be made specifically with the US market in mind.

As far as the home market was concerned, most of Britain's new models had been earmarked for export only. The need to repay the heavy loans that had arisen from World War 2 was of paramount importance and export earnings would help appreciably. Whilst Triumph were selling every motorcycle they could make, some were now needed to fulfil orders from this country's own dealers. However, before any of the new models could be despatched from Meriden, irrespective of their destination, there was need to launch the Thunderbird effectively so that it could attract strong orders in both this country and the USA.

A demonstration of speed and reliability seemed to offer the best prospects, especially as the prototype models had shown it should be possible to cover 500 miles at an average speed of 90mph. This had been confirmed during the testing of the prototypes, which had been entrusted to Tyrell Smith and Ernie Nott, both former road racers of some repute. Whilst this approach to the launch conflicted to some extent with Turner's own views about the folly of getting involved with racing, it had its advantages especially for the American market.

Nowhere existed in this country at that time for such a demonstration, so the track at Monthlery in France was booked, a banked circuit in some respects reminiscent of Brooklands. The riders selected for the test were Alex Scobie, Len Bayliss, Tyrell Smith, Bob Manns, Allan Jefferies and Jim Alves. Sadly, Ernie Nott had to be excluded as he was recovering from an injured shoulder caused when a gearbox locked up on him whilst he was riding flat out. He went to Monthlery, none-the-less, to provide welcome assistance in the pits. Perhaps surprisingly, the four machines were ridden to France, fitted with panniers, to carry all the equipment and spares likely to be needed, including tyres! Turner had decided to use three machines for the demonstration just to rub it in, the fourth being taken as a reserve.

The demonstration, officially observed by the ACU, ran like clockwork. Each of the three machines achieved the objective and even covered a flying lap at over 100mph at its conclusion. Edward Turner, who had been in the Monthlery pits for most of the test, was there to congratulate them after a stage-managed finale ensured all three machines could be photographed crossing the finish line together. There had been no need to use the fourth.

Back to Meriden

Back to Meriden

On the following day all four machines were ridden back to Meriden, after a detour for them to be photographed (appropriately) in front of the Arc de Triomphe. On arrival at the factory their riders and Turner himself were interviewed by the BBC. It had been a very convincing demonstration, bearing in mind the machines were running on 72 octane 'Pool' petrol, which restricted the compression ratio to only 7:1. Furthermore, all had been fitted with a Triumph spring wheel.

The first models to arrive in the USA were received with some initial disappointment when their performance was found to be below par. This was ultimately traced to the size of the carburettor, later replaced by one with larger bore. Another problem was the colour chosen for the Thunderbird's finish. The somewhat drab blue-grey colour did not go down very well with potential US purchasers either. As the result of strong dealer representations, the colour scheme was changed to a more pleasant lighter metallic blue for the 1951 season.

Attributed to Edward Turner

It has often been asked how the Thunderbird got its name, its choice being attributed to Edward Turner. Only recently has its true origin been revealed in the book Triumph in America by Lindsay Brooke and David Gaylin. It would appear that when Turner was driving to the Daytona Beach races in 1949 he came across the Thunderbird Motel in South Carolina, which had a representation of a giant eagle-like bird mounted on a pole in its grounds. It seemed such an appropriate name for the new model, especially with its North American connotations, that Turner adopted it immediately, along with a symbolic representation of the bird itself.

It is also interesting to recall that when the Thunderbird logo was used on a Triumph tie, its wearers were often mistaken by flight crews as a British Overseas Airways pilot. Quite unexpectedly, they found themselves the recipients of priority treatment!

The Thunderbird continued in production in its pre-unit construction form virtually unchanged until 1955, when its rigid frame was changed for one with pivoted fork rear suspension. Other modifications followed, mostly those that applied to the other models in the Triumph range including the use of the 'Slickshift' gearbox in 1958. In 1960 further changes took place, including the use of 18" wheels, and a full skirt rear enclosure, later reduced to more acceptable mid-frame panelling. The year following an alloy cylinder replaced the cast iron one used until now and in 1963 the transition to a unit-construction engine and gearbox took place, accompanied by a reversion to a single downtube frame. A 12 volt electrical system was also adopted at the same time.

The Thunderbird continued in production in its pre-unit construction form virtually unchanged until 1955, when its rigid frame was changed for one with pivoted fork rear suspension. Other modifications followed, mostly those that applied to the other models in the Triumph range including the use of the 'Slickshift' gearbox in 1958. In 1960 further changes took place, including the use of 18" wheels, and a full skirt rear enclosure, later reduced to more acceptable mid-frame panelling. The year following an alloy cylinder replaced the cast iron one used until now and in 1963 the transition to a unit-construction engine and gearbox took place, accompanied by a reversion to a single downtube frame. A 12 volt electrical system was also adopted at the same time.

The Thunderbird's 18 year run came at the end of 1966 by which time its sales potential had fallen dramatically. Triumph enthusiasts had deserted it in favour of the more powerful T110 or its successor, the T120 Bonneville. ![]()

See also When was it that? contents