When Edward Turner launched his first Triumph twin in 1937 it marked the beginning of his plan to replace all the older single cylinder models by twins. Based on al Page's original design, Turner had completely restyled the singles, to form the imaginatively-named 'Tiger' range. Finished in silver sheen with blue lining, offset by a great deal of chromium plating, they had formed the centrepiece of the Triumph display at the 1936 Motor Cycle Show. But it was time to move on and when the Tiger 100 twin made its debut at the 1938 Show, the 497cc Tiger 90 single was dropped from the range. Had it not been for World War 2, the Tiger 70 and 80 singles would have suffered a similar fate, as the 350cc 3T twin was already on the stocks. To have removed the 249cc Tiger 70 without a replacement twin would have been no loss. It had proved an expensive model to make and as Turner had said: "Every model is sold with a £5 note in the toolbox!"

As luck would have it, the 349cc Tiger 80 remained in production much later than intended, albeit in military guise. When the Triumph works were destroyed during the Coventry 'Triumph blitz' on November 14, 1940, the first batch of 3TW twins designed for use by the armed forces were destroyed with it. When a new location had been found for manufacture to continue and still useable machinery salvaged from the ruins of the old factory, only one option remained open — to make the 3HW single, a military version of the Tiger 80. Everything that related to the 3TW twin had been lost.

Triumph would not have had a lightweight model with which to maintain a stake in the lightweight market after the war had not Jack Sangster, Turner's boss, acquired New Imperial in 1939 after the company had been declared bankrupt. Now everyone knew what the simple NI tank transfer on the 1938 models had meant — nearly insolvent! Sangster had originally intended to continue the manufacture of these excellent models along similar lines, but Turner would have nothing of it. Instead, he set about the design of an entirely new 200cc single to carry the Triumph name. A prototype was up and running within six months, intended as a cheap utility machine with disc wheels, but it was dogged with problems. The war halted any further development and when post war production resumed it had to be dropped as Triumph were selling every twin they could make. Just as well, perhaps, as even Turner later described his prototype as "very agricultural in concept!"

Triumph would not have had a lightweight model with which to maintain a stake in the lightweight market after the war had not Jack Sangster, Turner's boss, acquired New Imperial in 1939 after the company had been declared bankrupt. Now everyone knew what the simple NI tank transfer on the 1938 models had meant — nearly insolvent! Sangster had originally intended to continue the manufacture of these excellent models along similar lines, but Turner would have nothing of it. Instead, he set about the design of an entirely new 200cc single to carry the Triumph name. A prototype was up and running within six months, intended as a cheap utility machine with disc wheels, but it was dogged with problems. The war halted any further development and when post war production resumed it had to be dropped as Triumph were selling every twin they could make. Just as well, perhaps, as even Turner later described his prototype as "very agricultural in concept!"

Entirely new 149cc

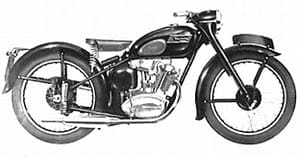

It was not until the 1952 Motor Cycle Show that Triumph sprang a surprise by unveiling an entirely new 149cc model to complement their 1953 range. The Triumph T15 Terrier had arrived, the first under 200cc model to be made by Triumph since their 150cc X0 series of 1934. Finished in the familiar amaranth red colour of the 5T speed twin it was indeed as their catalogue at the time proclaimed — a real Triumph in miniature. Suffice it to say it continued in production until August 1956, by which time it had been superseded by its bigger brother, the 199cc T20 Tiger Cub.

Manufacturers do not often ride their own products, but Turner was one exception. In his younger days he had been a very keen motorcyclist and pre war had won a race on the Crystal Palace path racing circuit on an ohc Velocette. Often he would take a bike out for test at Meriden to form his own opinions, to blast off down the road with his hat jammed tightly on his head. It mattered not that it had no number plates, or for that matter no trade plates either. As someone at the factory once said: "The police would not dare stop Edward Turner even if they could catch him", for on at least one occasion he had ridden off on a Grand Prix racer, megaphones and all!

Determined to find out for himself exactly how a Terrier would perform on a long distance run, he set out from Meriden on Monday, October 5, 1953, to ride from Land's End to John 0' Groats. He was accompanied by Bob Fearon, the Works Director, and Alex Masters, the Service Manager. All were mounted on identical T15 Terriers and kitted out with new Barbour suits and safety helmets. They were escorted by a car driven by John McNulty, with Eric Headlam as passenger. McNulty was observing the run to verify that it had not been 'rigged' in any way, and Headlam, Triumph's London representative, was there to ensure the pre-planned schedule was maintained. Following on a speed twin was Colin Swaisland, an Esso Cameraman filming the run.

They set out for the Imperial Hotel in Exeter where they would stay overnight before starting off on their long journey the following morning. Within the first hour of their departure all three riders had disappeared from the view of their followers whilst rounding a corner in what appeared to be a white cloud of cement dust. It was, in fact, liquid fertiliser shed by a lorry. This so-called 'fertilisation ceremony' later provided scope for no end of jocular comment!

They set out for the Imperial Hotel in Exeter where they would stay overnight before starting off on their long journey the following morning. Within the first hour of their departure all three riders had disappeared from the view of their followers whilst rounding a corner in what appeared to be a white cloud of cement dust. It was, in fact, liquid fertiliser shed by a lorry. This so-called 'fertilisation ceremony' later provided scope for no end of jocular comment!

They made their way to Roche the following morning so that they could call at the Victoria Inn, at which Alan Maclachlan, the former RAC motorcycle department manager was 'mine host'. Then they set off for their Land's End starting point. Their first overnight stop was to be at the Regent Hotel, Leamington, close to Turner's home. It was an eventful run and as Turner said on arrival "This is just the job — I needed it to jerk me out of the groove." Later he went on to say " Speaking purely as a rider I think this little Terrier has got something that's going to appeal to quite a lot of people." Bob Fearon was just as enthusiastic, claiming he had forgotten what fun motorcycling could be. He had found how much better he could view the countryside than from the inside of a car and smell it too.

The following day saw them in Carlisle, having travelled via Leicester, Doncaster, Scotch Corner and Penrith, stopping for lunch at Boroughbridge. They arrived an hour in front of schedule which caused Turner to say "Why aren't we scheduled to do more miles in a day? This is so easy it's just plain silly." He had, however, overlooked the fact that it had been prudent to make provision for rain, fog and other poor weather conditions that would hinder progress.

Friday dawned

As Friday dawned in Inverness they had only 158 miles still to cover. During their journey from Carlisle they had travelled a further 263 miles, passing through Lanark, Stirling, Perth, Killicrankie and Kingussie. The journey so far had been so easy such that it would have been easy for the riders to feel complacent. However, the weather forecast had not been favourable, suggesting the prospect of rain. Sure enough it was correct and rain began to fall soon after they had left Wick. It took its toll when Bob Fearon ran out of road when negotiating one of Scotland's never ending bends. Rather than drop his bike and stand a risk of jeopardising the run he hung on and ran wide on to the grass verge at the edge, to hit a hidden culvert that made his bike leap in the air. It was a heart stopping moment but somehow he managed to regain the road safely.

A mile further on his engine cut out. A battery lead had chafed, perhaps due to the incident. Rather than risk losing time making a repair it was decided to cover the remaining 50 miles with the ignition switch in the emergency start position. And so all three riders arrived safely in John O'Groats with time to drink a cup of coffee before they returned to Wick to take the official mileage over the four figure mark. It mattered not that it was now raining hard.

A mile further on his engine cut out. A battery lead had chafed, perhaps due to the incident. Rather than risk losing time making a repair it was decided to cover the remaining 50 miles with the ignition switch in the emergency start position. And so all three riders arrived safely in John O'Groats with time to drink a cup of coffee before they returned to Wick to take the official mileage over the four figure mark. It mattered not that it was now raining hard.

When the results were analysed it was found the riders had covered 1008 miles in a total running time of 27 hours 29 minutes. This represented an average speed of 36.68mph, a considerable improvement on their estimated average speed of 30mph. Fuel consumption had averaged an incredible 100.6mpg! To put this in its correct perspective the weight of the individual riders should also be taken into account. Turner weighed 14 stone 3 pounds, Masters 13 stone 7 pounds and Fearon 16 stone, 7 pounds. It had been a memorable run from the riders' point of view and as a public relations exercise it had given Triumph's new lightweight a considerable boost. The motorcycling press promptly dubbed it the 'gaffer's gallop' and each rider was presented with a memento in the form of a specially bound album of photographs taken during the run. ![]()

See also When was it that? contents