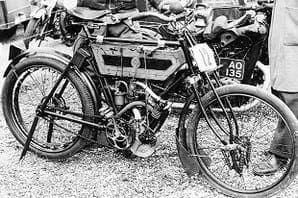

Sunbeam was yet another British manufacturer late to enter the burgeoning motorcycle industry, in 1912. Already renowned for the high quality bicycles they made in their Wolverhampton factory, their founder, John Marston, decided to manufacture a motorcycle of similar quality. To get the project started he took on John Greenwood, who previously had been employed by both Rover and JAP. It was a wise choice as he was actively involved with the design of virtually every Sunbeam motorcycle until his retirement in 1934. However, circumstances were such that the engine design for the new model had already been entrusted to Harry Stevens, another native of Wolverhampton, well experienced in this field. Harry was one of the four Stevens brothers, soon to be making their own motorcycles bearing the initials AJS. Indeed, the payment he received from John Marston helped meet the cost of their first production run, an interesting but little known fact that reveals this early link between the two respective companies.

The history of the Sunbeam company is already well documented in the now out of print book The Sunbeam Motorcycle by R. Cordon Champ, published by GT Foulis in 1980.

Suffice it to say that quite apart from making a very fine but expensive 'gentleman's' motorcycle, with a finish that was second to none, Sunbeam also enjoyed an enviable record of success in competition events of all kinds. They won the Senior TT in 1920, 1922, 1928 and 1929, with innumerable good placing, having riders such as Alec Bennett, Charlie Dodson, Tommy de la Hay and Graham Walker. Furthermore, although the legendary George Dancethad little success in road racing, he was virtually unbeatable in sprint racing events. There was even a Sunbeam dirt track racer and an overhead camshaft model, although sadly these latter models failed to make much impact on the sporting scene.

Suffice it to say that quite apart from making a very fine but expensive 'gentleman's' motorcycle, with a finish that was second to none, Sunbeam also enjoyed an enviable record of success in competition events of all kinds. They won the Senior TT in 1920, 1922, 1928 and 1929, with innumerable good placing, having riders such as Alec Bennett, Charlie Dodson, Tommy de la Hay and Graham Walker. Furthermore, although the legendary George Dancethad little success in road racing, he was virtually unbeatable in sprint racing events. There was even a Sunbeam dirt track racer and an overhead camshaft model, although sadly these latter models failed to make much impact on the sporting scene.

Like most other companies Sunbeam found the going difficult during the late 20s as the effects of the oncoming depression began to make themselves felt. Their immediate future was, however, assured when, in 1928, they were acquired by Imperial Chemical Industries. Initially, there was little evidence of this take-over, but by 1931 changes were implemented which meant the company no longer made every part used in their assembly. Inevitably this began to have its effect on the quality of the product and when it became obvious the old production equipment was virtually worn out, it was some time before the necessary reinvestment in the machinery to replace it took place. Design stagnated and by 1935 the company made their last racing machine, the model 95, outclassed by its contemporaries.

Further surprise

Although some of the more sporting models continued to be made, a further surprise during late 1936 again affected the destiny of the company. As the result of somewhat clandestine negotiations, Sunbeam was acquired by Associated Motor Cycles, who had already bought AJS after this latter company had gone into voluntary liquidation during 1931. AMC purchased both the motorcycle and bicycle activities of Sunbeam and set them up as two separate companies, giving as their registered address their main site address in Plumstead, south east London.

Initially, motorcycle production continued in Wolverhampton, but when ICI required the works for other activities, all motorcycle production was transferred to Plumstead. Although several of the older Sunbeam models remained in production, albeit with certain modifications, it was late in 1937 that an entirely new model was added to the range. Available in a range of capacities from 248cc to 598cc it had an engine of the high camshaft type, an arrangement that gave the outer appearance of an ohc model and had the name Sunbeam emblazoned in script across the timing cover. Although it was a very heavy model, a competition version of the 500cc model met with some success in the hands of Geoff GodberFord, who rode it in trials. But before it could make much impact, World War 2 intervened and Geoff had to be called back from Germany on the last day of the 1939 International Six Days Trial where he was putting up another good performance.

Yet another change of ownership took place during late 1943, at the time when BSA were beginning to think about what they should do after the war when armaments would no longer be a major requirement. Aware of the success of Raleigh in the bicycle world they decided to extend their own range of bicycles and approached AMC to enquire about purchasing the Sunbeam bicycle side of their business. They did so at just the fight time, as AMC had already decided to concentrate on making as many motorcycles as possible and terminate the production of bicycles. After agreeing to buy the Sunbeam bicycle name, as well as all their jigs and tools, BSA set up Sunbeam Cycles Limited so that they could produce bicycles under this name as soon as the war had ended. AMC were also anxious to get rid of the Sunbeam motorcycle jigs and tools, so these too were included in the deal, although they were never used and ultimately destroyed.

Yet another change of ownership took place during late 1943, at the time when BSA were beginning to think about what they should do after the war when armaments would no longer be a major requirement. Aware of the success of Raleigh in the bicycle world they decided to extend their own range of bicycles and approached AMC to enquire about purchasing the Sunbeam bicycle side of their business. They did so at just the fight time, as AMC had already decided to concentrate on making as many motorcycles as possible and terminate the production of bicycles. After agreeing to buy the Sunbeam bicycle name, as well as all their jigs and tools, BSA set up Sunbeam Cycles Limited so that they could produce bicycles under this name as soon as the war had ended. AMC were also anxious to get rid of the Sunbeam motorcycle jigs and tools, so these too were included in the deal, although they were never used and ultimately destroyed.

There was no question of BSA wishing to resurrect the overweight pre war high camshaft Sunbeam, or for that matter, any other of that marque's designs. Instead, they decided to start with an entirely new model and engaged Erling Poppe as its designer. Already BSA had acquired the right to make a mirror copy of the DKW RT125 as a result of war reparations, which resulted in them producing the machine we know today as the Bantam. They had also shown an interest in the R75 BMW, which had been used by Germany's armed forces during the war – a 750cc side valve flat twin sidecar outfit with sidecar wheel drive. Subsequent design studies had impressed them and it was an adaptation of the 'rolling chassis' of this outfit, less the sidecar, that was used for the running gear of the new Sunbeam model. Although not an exact copy, the family likeness was all too obvious. There was, however, no intention of using a horizontally opposed twin cylinder engine to power it. Instead, BSA rummaged through their archives and came up with a design for an in-line twin power unit that had reached the prototype stage during the early 30s. Appearing suitable for the proposed new model it was substantially updated and a gearbox designed that would provide the advantage of shaft final drive. However, therein lay a hidden disadvantage as the gearbox incorporated a bevel drive system so that a conventional kickstarter could be used. This, along with a number of other reasons, dictated the use of a worm drive for the rear wheel spindle, which was to prove the Achilles' heel of the new model.

Hemispherical combustion chambers

The original 487cc engine to be used in the new design was of the overhead camshaft type, with hemispherical combustion chambers and a cross flow induction and exhaust system, the carburettor being on the left hand side. It proved surprisingly lively during the early testing, so much so that it was possible to exceed 90mph. Unfortunately this was more than the worm final drive could take, which ran very hot and wore out after 5,000 miles! To eliminate the worm final drive arrangement would have necessitated almost complete redesign of the power unit, so Poppe had to revert to the only other option – to detune the engine by rearranging the top half of the engine. The now less efficient engine produced only about 25bhp, and had a reduced maximum speed not much above 70mph. It might have been an uneasy compromise, but it worked.

The front fork used on the early models struck new ground. Although of the telescopic type and similar in appearance to the BMW original, it was undamped. Rather than have the springs contained within the individual fork legs, a separate central unit housed a single spring connected to the fork sliders by a substantially-made bridge piece. Provision was made for lubrication by grease gun. Although the prototype had a rigid frame in the expectation that there would be both rigid and spring frame versions available, only the latter went into production.

With it went another early post war BSA feature, the speedometer mounted in the tank top. The frame that went into production had conventional plunger type units, undamped as is usual with this type of suspension. One obvious continental feature remained in the form of the cantilever saddle, which needed no rear mounting points. Specially made by Terry, it hinged on a bonded rubber bush that connected with a long spring contained within the top tube of the frame, with provision for adjustment to suit rider weight. What may seem surprising is that the front fork spring unit, the rear suspension and the saddle tube were filled with cotton wool soaked in oil, in the pious hope that the oil would be distributed in the form of oil mist, a feature often relied upon by designers that so often proved far from satisfactory. The most prominent feature of the new Sunbeam was its large section tyres, which at first were of 4.75×16" section. These, and the fact that the engine was rigidly bolted to the frame, gave rise to handling problems, not helped by severe engine vibration.

Eventually, the engine had to be rubber-mounted, with 'snubbers' to limit its movement within the frame and a flexible section incorporated in the joint between the two-into-one exhaust pipe and the silencer. These modifications and the use of 4.50×16" section ribbed front tyre brought about some improvement, although the latter change meant the wheels were no longer interchangeable.

Eventually, the engine had to be rubber-mounted, with 'snubbers' to limit its movement within the frame and a flexible section incorporated in the joint between the two-into-one exhaust pipe and the silencer. These modifications and the use of 4.50×16" section ribbed front tyre brought about some improvement, although the latter change meant the wheels were no longer interchangeable.

Although prospective purchasers were attracted by the novelty of the design and the fact that it was the first entirely new design to emerge after World War 2, the Sunbeam S7 twin never achieved anything like the success intended. Even publicity stunts like getting George Dance out of retirement to ride it had little effect. By the time it appeared at the 1948 Motor Cycle Show, the first to be held after the war, it was already accompanied by its S8 version, which used a conventional BSA telescopic front fork and wheels and tyres of normal section. Many saw this as an admission of failure in the original design. Priced at £200, plus £54 purchase tax, the S7 failed to compare favourable with many of its contemporaries. The new Norton vertical twin, for example, retailed at a basic price that was £30 less, at a time when every extra pound counted. Perhaps surprisingly, the S7 and S8 remained in production until 1958, when both were discontinued. The Sunbeam dynasty had finally come to an end, discounting a short lived attempt to use the name on a Triumph-designed scooter or on bicycles and toys. One can only speculate on what might have happened if the four cylinder prototype had ever gone into production, based on a BSA car-type engine. ![]()

See also When was it that? contents