The recession of the late 20s hit the motorcycle industry particularly hard causing many of the smaller manufacturers to disappear almost overnight. Undercapitalised and often assembling in small numbers a machine that bore their name from a miscellany of bought-in parts, they stood little chance of survival. In the main most of the larger manufacturers somehow managed to weather the storm, even if they had to endure a particularly lean time and add to their range what today is known as an 'entry' model. Prices were cut to the bone and profit margins were reduced to an unbelievably low level. Yet even the 'big boys' were not entirely immune from oblivion. Who would have thought that AJS of Wolverhampton would be forced into voluntary liquidation towards the end of 1931? Run by the Stevens family, the company had a long and proud history, with a comprehensive model range and an enviable record of success in competition events. They, more than most of their contemporaries, should have been well able to hold out until better times helped restore their fortunes.

In point of fact AJS happened to be in a particularly disadvantaged situation when the recession struck because they had encountered financial difficulties several years before it began to bite in earnest. A precursor of what was to follow manifested itself in 1926 when the company was unable to pay its shareholders a dividend. This was due not only to a marked decline in motorcycle sales but also to an unsuccessful attempt at diversification into the manufacture of wireless sets. Still convinced that diversification seemed the only way in which to revert to full production, the company ventured into the manufacture of commercial vehicles and also secured a contract to make the bodywork for a Clyno lightweight car.

Sadly, these diversifications were also doomed to failure in the long term, leaving the company in a precarious position with a hefty outstanding loan from the Midland Bank. The end came in 1931 when shock waves from the Wall Street crash of 1929 worsened the already precarious UK economy. With so many businesses failing and AJS the bank manager got the jitters and called in the company's loan.

Sadly, these diversifications were also doomed to failure in the long term, leaving the company in a precarious position with a hefty outstanding loan from the Midland Bank. The end came in 1931 when shock waves from the Wall Street crash of 1929 worsened the already precarious UK economy. With so many businesses failing and AJS the bank manager got the jitters and called in the company's loan.

Although AJS were able to meet this in full, in doing so they placed themselves in a negative cash flow situation. Now the only option left was to go into voluntary liquidation, which they did in the knowledge that they would eventually be able to pay all their creditors in full. Their motorcycle business was bought by the Collier Brothers, who kept the AJS name alive by amalgamating it with their own Matchless trade mark and transferring manufacture to south London.

Aptly name Retreat Street

The Stevens family had one card left to play. They still owned the works in the now aptly named Retreat Street, where Joe Stevens Senior had founded the Stevens Screw Company Limited in 1906. Harry Stevens, the eldest of Joe's five sons, remained convinced the commercial vehicle market still offered good prospects, having in mind a light economic runabout that would appeal to tradesmen who needed to make deliveries within a short distance of their home base. During May 1932 he assembled a small workforce to make a three wheeled light commercial van powered by a 588cc water-cooled side valve single cylinder engine. With a load carrying capacity of 5cwt, low running costs and a maximum speed of approximately 45mph it seemed to fulfil his objectives admirably. Later versions had a fully sprung chassis rather than just the bodywork and an increased pay load capacity of 8cwt. As chain drive to the van's rear wheels had proved to be its Achilles Heel, shaft drive was substituted with beneficial results.

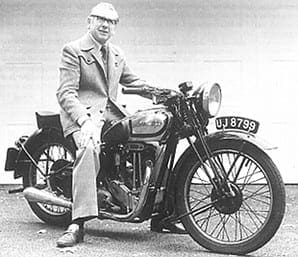

The success of the three wheeler inevitably led to thoughts about making a motorcycle. After supplying motorcycle engines under the Ajax name to OK Supreme and AJW, Harry Stevens tentatively re-entered the motorcycle market during early 1934 with a complete 249cc ohv model.

Subject of a road test

The new DS1 model was the subject of a road test in the November 14 issue of Motor Cycling in which it received favourable comments. Although it had to be marketed under the Stevens' name as the sole right to the use of the AJS trade mark had been included in the sale of the old company to Colliers, its allegiance to its predecessors was immediately obvious. Two versions were available, the DS1 with a downswept exhaust system, or alternatively the identical US2 model on which it was upswept. The overall specification of both models broadly followed that of the contemporary models of the era, featuring dry sump lubrication, a four speed foot change gearbox (Burman), and partially enclosed valve gear. First impressions were good. Despite the fact that the machine was brand new and still had to be run in, a speed of over 60mph was obtained in top gear.  Minimum non-snatch speed in the same gear was 20mph. Road holding and braking met expectations and fuel consumption averaged over 80mpg at 35 to 40mph. Points that received special comment from the tester related to the rubber-mounted handlebars, the large diameter headlamp, the robustness of the footrest assembly, and the adequacy of the toolkit. With regard to the last mentioned, routine maintenance was easy.

Minimum non-snatch speed in the same gear was 20mph. Road holding and braking met expectations and fuel consumption averaged over 80mpg at 35 to 40mph. Points that received special comment from the tester related to the rubber-mounted handlebars, the large diameter headlamp, the robustness of the footrest assembly, and the adequacy of the toolkit. With regard to the last mentioned, routine maintenance was easy.

Both models were priced at £51 fully equipped, although an extra £2.10s had to be paid for a speedometer, 18s.6d for a pillion seat and pillion footrests, and an additional £1.10s for a chromium plated petrol tank. Whilst no doubt the price structure had taken into account that production was in relatively small numbers, and also the build quality, it still represented a relatively expensive acquisition compared with many of its contemporaries.

A 348cc version followed in 1935, and soon after that a 495cc model completed the range, all of similar design. It would be pleasing to report that the Stevens family managed to regain a foothold in the motorcycle market, but sadly even this was denied them. Production of the three wheelers ceased at the end of 1936 and the motorcycles were no longer made after the summer of 1938. Limited sales meant that they could not be more competitively priced and because of the break in continuity they could no longer trade on the successes of their predecessors. The company's last involvement with motorcycle engines occurred during 1938 when George Brough asked them to make the horizontally-opposed four cylinder engine for his prototype 996cc Golden Dream model, which was to be displayed at that year's Motor Cycle Show. They had their own views about the design of this engine, which they kept to themselves!

Although part of the land that was once the home of A.J. Stevens & Co. (1914) Ltd., is now the site of a supermarket, it is pleasing to note that its past history has not gone unmarked. Its new owners have ensured a futuristic looking statue of a speeding motorcyclist takes pride of place in its grounds. ![]()

See also When was it that? contents