Unlike some of the other motorcycle manufacturers, the Scott Motor Cycle Company did not supply motorcycles to the armed forces during World War 2. Instead, they became involved in war work of a different nature, some of which came from the Admiralty. Single cylinder models of rugged construction, needing only a minimum of maintenance to keep them in running order seemed to offer the best prospects, and it was their manufacturers that got the contracts from the War Department. As Scott owners will admit with reluctance, their beloved but often temperamental water-cooled two-stroke twins would hardly have met these requirements!

Production resumed

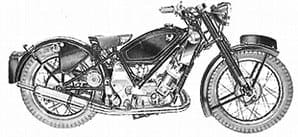

When motorcycle production resumed during 1946, the Scott continued much as before, retaining the Flying Squirrel name but now available with only a 596cc engine. The most noticeable difference was new full-width wheel hubs. Made of cast iron, with a ribbed exterior, they looked very fashionable. The front hub had a brake at either end and a built-in speedometer drive on the right, the brakes being operated via a balance box above the front mudguard. It contained a pulley over which ran the cable linking the two brake operating arms. Another cable from the handlebar-mounted brake lever was attached to a 'stirrup' astride the pulley, which caused it to rise when the brake was applied. It was ingenious and beautifully made, both halves of the alloy casting being held together by small bolts around its periphery.

Though very effective, the balance box must have been expensive to make, when a twin cable system from the handlebar lever would have proved simpler and cheaper. Yet for all that, the front brake showed no real advantage over its predecessor in terms of stopping power. The rear brake suffered the disadvantage of not having its alloy brake plate ribbed internally, to strengthen it. The first occasion on which the brake was applied fiercely would cause it to distort permanently and thereafter its efficiency was impaired.

Though very effective, the balance box must have been expensive to make, when a twin cable system from the handlebar lever would have proved simpler and cheaper. Yet for all that, the front brake showed no real advantage over its predecessor in terms of stopping power. The rear brake suffered the disadvantage of not having its alloy brake plate ribbed internally, to strengthen it. The first occasion on which the brake was applied fiercely would cause it to distort permanently and thereafter its efficiency was impaired.

The cast iron hubs added significantly to the overall weight of the post-war Scott, which was not disclosed in the manufacturers catalogue. Priced at £252.1s 11d inclusive of purchase tax, the Flying Squirrel was some £70 more expensive than a BSA A7 twin and £54 more expensive than a Triumph Tiger 100. You had to be an enthusiast to buy one! It is alleged the first six models to leave the production line were fitted with a Brampton girder fork, but at least one other surviving model is fitted with a Webb. Works records show almost 100 engines were made during the 1946 season, although the production figure for the year's output of complete machines was not disclosed.

Girder fork

It soon became obvious that the girder fork needed to be replaced by a telescopic front fork if the machine was to prove attractive to prospective purchasers. Scott, in company with Panther and Velocette, sought salvation in the propriety Dowty Oleomatic design. It was unusual in having no internal springs, relying solely on air as the suspension medium, with oil to damp its movement. It worked well, with the proviso that the seals were in good order. Compressed air is not easy to contain within a confined space, especially when subjected to constantly varying loads.

The original wheel hubs and twin front brake were retained when the Dowty forks were fitted, a larger diameter front wheel spindle being needed. Furthermore, the front wheel speedometer drive was transferred to the gearbox outrigger bearing assembly on the left-hand side of the machine. The old, familiar, rear stand was replaced by a centre stand.

The original wheel hubs and twin front brake were retained when the Dowty forks were fitted, a larger diameter front wheel spindle being needed. Furthermore, the front wheel speedometer drive was transferred to the gearbox outrigger bearing assembly on the left-hand side of the machine. The old, familiar, rear stand was replaced by a centre stand.

Many now required rear suspension in addition to a telescopic front fork. Using a plunger-type frame not unlike that of the pre-war Clubman's Special spring frame model, a prototype was constructed at the works with a view to making it available in 1950.

It never made its debut, however, as the money was not available for its further development. As may be imagined, it was also heavier than the rigid frame model, which reflected badly on its performance.

Lucas Magdyno

Further changes in the production model were made for the 1949 season. Gone was the Lucas Magdyno, to be replaced by coil ignition and a Lucas pancake dynamo mounted on the left-hand crankcase door, driven directly from the crankshaft. The familiar Pilgrim oil pump was still mounted on the right-hand crankcase door, but interposed between the drive and the pump was a skew gear, to drive a distributor located vertically behind the right-hand cylinder. No longer was there need for a long chain to drive the magdyno, the space vacated by the latter being used to advantage by a five-pint oil tank on the right-hand side. The petrol tank now had no need to incorporate a separate oil compartment, although it retained its characteristic shape. It was claimed the coil ignition made starting easier and gave better slow running, as well as improving acceleration. Despite all these modifications, the price had been reduced slightly to £247.0s.3d, but the company refrained from displaying their new model at the first post-war Motor Cycle Show.

During the first half of 1950 a brief notice in the motorcycling press stated the Scott Motor Cycle Company had gone into voluntary liquidation, following a meeting of creditors. Two shareholders had purchased the company's assets with the objective of forming a new company, and the services of the principal executives of the old company had been retained. The reason for the old company's demise became apparent when it was disclosed only 600 post-war models had been made.

During the first half of 1950 a brief notice in the motorcycling press stated the Scott Motor Cycle Company had gone into voluntary liquidation, following a meeting of creditors. Two shareholders had purchased the company's assets with the objective of forming a new company, and the services of the principal executives of the old company had been retained. The reason for the old company's demise became apparent when it was disclosed only 600 post-war models had been made.

Towards the end of 1950, it was announced the Flying Squirrel would continue in production unchanged, its manufacture being transferred to Matt Holder's Aerco Jig and Tool Company, in Birmingham. Matt had been a Scott enthusiast ever since a young man, so there was consolation that this historic marque remained in good hands. The old works in Shipley were subsequently acquired by Hepworth and Grandage, the manufacturer of Hepolite pistons.

The Scott saga was by no means over yet, but what followed is another story in itself. It may well be recalled in this series at a later date. ![]()

See also When was it that? contents