Few will be aware that John Alfred Prestwich, the founder of the north London company that made the famous JAP engine, was at first a pioneer of cinematography. His contribution to the early days of the cinema was substantial, as will be evident to anyone who visits the Barnes Museum of Cinematography in St Ives, Cornwall. Scott's ill-fated expedition to the Antarctic was filmed on one of his cine cameras, as was Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee.

Exactly why he later had an all consuming interest in the internal combustion engine is by no means clear, but when he redirected all his energies in that direction he forsook completely his other interest.

The first JAP engine was advertised in the June 17, 1901 issue of The Motor Cycle, a 2½hp automatic inlet valve engine intended to be clipped to the front downtube of a bicycle. For a short while he was able to offer a complete JAP motorcycle, using bought in components for the cycle parts, probably supplied by BSA. Initially the engines and the complete machines were made and sold from his home in 1 Lansdowne Road, Tottenham, but in early 1911 he was able to move production to a purpose built factory in nearby Northumberland Park.

By now he was making engines in considerable numbers, both singles and twins, and had even ventured into aviation by making ohv vee-eight engines, both air cooled and water cooled. One of these engines was used to power a Willows airship during its record breaking flight from Cardiff to the Crystal Palace in 1910, and another to power the JAP monoplane to be seen suspended from the roof in the Science Museum, South Kensington.

Needless to say, J.A. Prestwich & Co had to face up to fierce competition from other proprietary engine manufacturers such as Precision and later, Blackbume. Somehow, JAP managed to keep the upper hand, largely on account of the quality of their engines and their many racing successes that included numerous world records. It was not until 1925 that a hint in the change of the company's fortunes became evident when they closed their Racing Department. It meant that they lost the person who, arguably, was Britain's foremost motorcycle engine designer, Val Page. With him went Bert Le Vack, a development engineer and rider of outstanding ability. Page went to Ariel and Le Vack to New Hudson, both of them to make an impression with their new employers in a very short period of time.

Needless to say, J.A. Prestwich & Co had to face up to fierce competition from other proprietary engine manufacturers such as Precision and later, Blackbume. Somehow, JAP managed to keep the upper hand, largely on account of the quality of their engines and their many racing successes that included numerous world records. It was not until 1925 that a hint in the change of the company's fortunes became evident when they closed their Racing Department. It meant that they lost the person who, arguably, was Britain's foremost motorcycle engine designer, Val Page. With him went Bert Le Vack, a development engineer and rider of outstanding ability. Page went to Ariel and Le Vack to New Hudson, both of them to make an impression with their new employers in a very short period of time.

The situation that prompted this action had come about because most of the leading motorcycle manufacturers were now designing and making their own engines, leaving only the smaller fry as JAP customers. Fortunately, the decline in the company's business was slow to begin with and offset by further diversifications later on that included the manufacture of pencils at a rate of 1,500,000 a week by 1951 through their subsidiary, Pencils Limited. By the early 30s they had also commenced the manufacture of a comprehensive range of stationary engines for industrial use, using their expertise to good purpose.

Another business opportunity

It was at the 1929 Motor Cycle Show in Olympia that another business opportunity presented itself. Speedway racing had come to Britain during February that year and had created a tremendous initial impact. Within a very short period of time almost every motorcycle manufacturer was keen to make what was then known as a dirt track model in order to break into a market that seemed to offer good prospects. They needed all the business they could get as Britain was in the grip of a recession.

Almost from the start of dirt track racing as it was first known, Douglas virtually dominated it, that is until the dirt track Rudge came along to challenge it and encourage a different riding style. Some of the leading riders thought it was about time JAR showed an interest in view of their long standing record of competition successes. Bill Bragg, at that time the Captain of the Stamford Bridge team, was determined to do something about it and in company with several other riders he visited the JAP stand at the show. It was fortunate that Vivian Prestwich, one of John's five sons, happened to be on stand duty at the time. A keen competitor himself in sprint and other racing events, he was sympathetic to their approach, even though his father had already decided speedway racing would be no more than a 'flash in the pan' and short lived. He prevailed upon him to think again and was successful in getting a speedway engine development programme started under the control of Stan Greening, their Chief Technical Advisor.

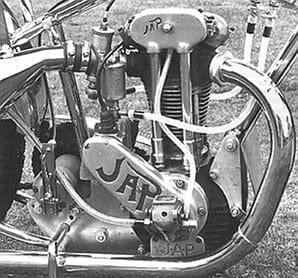

Stan's initial move was to take the 350cc engine with which he and Teddy Prestwich had set up a number of world records at Brooklands. He substituted a 500cc cylinder barrel from which the cooling fins had been cut back to reduce weight, and fitted a twin port cylinder head from a 'roadster' engine after the combustion chamber had been reshaped. Although the overall weight of the engine had been reduced by 11lbs, it was still too heavy and was well down on power compared with the four valve Rudge. In the search for more power and a further reduction in weight, Stan experimented with cam design as well as port shapes and angles. He also skimmed the flywheels to achieve a useful weight reduction. A small number of modified engines were made available to three leading riders of the day, and installed in Harley-Davidson 'peashooter' frames.

Stan's initial move was to take the 350cc engine with which he and Teddy Prestwich had set up a number of world records at Brooklands. He substituted a 500cc cylinder barrel from which the cooling fins had been cut back to reduce weight, and fitted a twin port cylinder head from a 'roadster' engine after the combustion chamber had been reshaped. Although the overall weight of the engine had been reduced by 11lbs, it was still too heavy and was well down on power compared with the four valve Rudge. In the search for more power and a further reduction in weight, Stan experimented with cam design as well as port shapes and angles. He also skimmed the flywheels to achieve a useful weight reduction. A small number of modified engines were made available to three leading riders of the day, and installed in Harley-Davidson 'peashooter' frames.

Sadly, they were not much better, being something like 2bhp down on the Rudge engine. With their nightly takings threatened the three riders pulled out and went their own way, refusing to co-operate any further.

It was then that salvation came in the form of Wal Phillips. Wal had previously worked for JAP in the days when his uncle, Bert Le Vack, was also employed by them. Already a proficient speedway rider he had just swapped his Douglas for a dirt track Rudge and when the news of this reached Stan Greening, he asked if Wal could borrow the machine. Wal agreed and in a very short time it was stripped down completely in Stan's workshop so that he could fmd out for himself why it performed so well. Working in conjunction with Wal, the two of them set to in their own time, after the factory had closed for the day, to modify the JAP engine in accordance with all the data they now had available. There would remain, however, one significant difference between the two engines – the JAP design persisted with a two valve cylinder head. They worked late into the night on more than one occasion and became so absorbed in what they were doing that they overlooked the noise the engine was making when running flat out on the dynamometer.

Those who lived close to the factory however, didn't, and the complaints came rolling in! The transformation of the engine did the trick as it now put out 33bhp against its earlier reading of 27. Furthermore its weight had been reduced from a staggering 97 to 53Ibs! Amal came up with a track racing carburettor to suit it and Lodge with a sparking plug that would withstand the heat.

Stamford Bridge

At its first try-out at Stamford Bridge the following Saturday Wal lapped at over 46mph according to unofficial timing, and was inside the track's record, despite handling problems. A prototype Wallis frame had been used to house the engine and after that had been modified in accordance with Wal's instructions, the Wallis-JAP made an impressive debut during the 1930 season.

In its heyday the JAP speedway engine was the world's most powerful unsupercharged engine of its kind, with a power output equivalent to that of a 490cc Manx Norton. It was an awesome beast to ride too, with an incredible amount of torque and a throttle that operated like an on-off switch. As veteran speedway rider Lew Cain says today "if you can ride a JAP you can ride anything."

Of all the speedway bike manufacturers Alec Jackson's Rotrax JAP was probably the most popular, although quite a few riders achieved good results using a frame of their own design and manufacture. The ultimate JAP was the four valve dohc version with which the late Mike Erskine was involved, after JAP had ceased to make these engines. ![]()

See also When was it that? contents