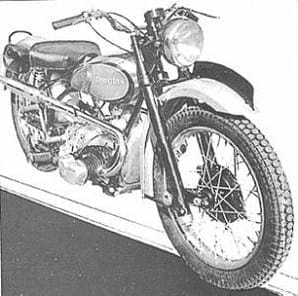

When Douglas released their first announcement about their post-war twin to coincide with the Bristol Engineering Exhibition in September 1945, it created quite a sensation. Although the company had remained faithful to their flat twin engine, it was now mounted transversely in the frame, and not in line with it as had been their general practice before.

Perhaps more intriguing was the fact that the new cradle frame used torsion bars for the rear suspension which, although undamped, gave no less than six inches of travel at the rear wheel. George Halliday, then working for the company under its old name of Aero Engines Ltd. had patented a number of torsion bar suspension arrangements towards the end of the war, and even intended using them for the front fork. Unfortunately, they failed to provide sufficient movement at the front end, which led to the design of the Radiadraulic leading link fork by Walter Moore, an old employee of the company who had returned to Douglas and Bristol, his home city, after the war. The new fork assembly was drawn up by a young draughtsman who was yet to make a name for himself in the British motorcycle industry – none other than Doug Hele.

The long rear suspension torsion bars were contained within the lower tubes of the cradle frame, and attached to the rear swinging fork by a bell crank arrangement. This has mystified many an onlooker who has looked in vain for the rear suspension units! The engine itself resembled the BMW layout in general terms, with the gearbox combined with the engine unit to form a massive alloy casting. The clutch was large in diameter and of the car type, providing the drive to the four-speed gearbox. Sadly, the company never had the money to include final drive by shaft. Instead, bevel pinions were used to turn the drive through ninety degrees for the time honoured-sprocket and chain arrangement. Each cylinder had its own Type 4 Amal carburettor and there was generous mudguarding, the front mudguard being attached high up the fork outers so that it did not move with the front wheel and resembled a parrot's beak in profile.

The long rear suspension torsion bars were contained within the lower tubes of the cradle frame, and attached to the rear swinging fork by a bell crank arrangement. This has mystified many an onlooker who has looked in vain for the rear suspension units! The engine itself resembled the BMW layout in general terms, with the gearbox combined with the engine unit to form a massive alloy casting. The clutch was large in diameter and of the car type, providing the drive to the four-speed gearbox. Sadly, the company never had the money to include final drive by shaft. Instead, bevel pinions were used to turn the drive through ninety degrees for the time honoured-sprocket and chain arrangement. Each cylinder had its own Type 4 Amal carburettor and there was generous mudguarding, the front mudguard being attached high up the fork outers so that it did not move with the front wheel and resembled a parrot's beak in profile.

Shipped overseas

The original T35 model had its limitations. Most of the early models which were shipped overseas to aid the export drive had their frames break, and had to be returned. Furthermore, the engine was none too lively either, and was inclined to prove somewhat thirsty. Erling Poppe, who had designed the Sunbeam S7, was by this time the Technical Director at Douglas. He did his best to resolve the engine problems, but without much success. It was then that another ex-Douglas employee came into the picture – Freddie Dixon.

Freddie worked wonders with the engine in a very short period of time, and as a result, the T35 model was replaced by the so- called Mark III version, which had a greatly improved engine. The engine differed externally by having rocker covers with a cut-out in the top surface to accommodate the sparking plugs, which were now mounted in the redesigned cylinder heads at a much shallower angle.

They no longer carried the cast-in Douglas name. The carburettors and inlet ports had rearranged so that they were now in the downdraught position. The cylinder barrels had a different finning pattern too. Internally, both valves were now of the same stem length and the pistons of the flat top variety.

They no longer carried the cast-in Douglas name. The carburettors and inlet ports had rearranged so that they were now in the downdraught position. The cylinder barrels had a different finning pattern too. Internally, both valves were now of the same stem length and the pistons of the flat top variety.

The cylinder barrels had different centres for the larger diameter cylinder head retaining studs, and the heads themselves a different shape combustion chamber. By this time (1948), the Mark III model had become the fastest 350 on the road.

Having shown its potential, it was now evident the Mark III was capable of being developed still further. In no time at all a standard road model was converted to provide a more sporting image.

This was accomplished by fitting mudguards that were less heavily valanced, having an upswept twin exhaust pipe system that terminated in separate Burgess "straight through" silencers, twin tool boxes, one each side of the sub-frame, upswept handlebars with a quicker action twist grip, and a comprehensive air cleaner arrangement. Cyril Quantrill of Motor Cycling was one of the first journalists to try out the new model, which he took over part of the Lands End Trial cours e during April 1948. He was impressed, and it is fair to say the Sports Model of 1948/9 is reputed to be the best of all the early post-war models. Although it shared the same engine unit as the standard Mark III model, it seemed so much more lively. Various theories have been put forward to account for this, but probably the most inhibiting factor on the standard models was the alloy `woffle box' silencer under the gearbox into which the two short exhaust pipes fed. It seems certain this latter arrangement would have proved more restrictive.

e during April 1948. He was impressed, and it is fair to say the Sports Model of 1948/9 is reputed to be the best of all the early post-war models. Although it shared the same engine unit as the standard Mark III model, it seemed so much more lively. Various theories have been put forward to account for this, but probably the most inhibiting factor on the standard models was the alloy `woffle box' silencer under the gearbox into which the two short exhaust pipes fed. It seems certain this latter arrangement would have proved more restrictive.

Further development led, in due course, to the evolution of the Plus models, and an even more specialised trials model with a rigid frame. Surprisingly, all this happened against a background of mounting financial problems, which always seemed to plague the company throughout its 50 year existence.

Yet despite the Official Receiver being called in during 1949, the company somehow managed to survive until 1956, with Eddy Withers taking their competition activities under his wing from his premises in West Norwood – virtually the London Douglas Depot.

One of the greatest accomplishments of the Sports Model occurred when Don Chapman, of the London Douglas MCC, entered one of these models in the 350cc Race at 'Motor Cycling's Silverstone Saturday Meeting' in 1950. Despite the fact that a number of the new 90 Plus Models had been entered in the same race, Don and his Sports Model had assumed a commanding lead by half distance, to continue to win, relegating R.A. Smith and his Gold Star BSA to second place. To prove that even the standard Mark III models were no slouches either, a team of three had been entered by the London Douglas MCC in the 1949 Junior Clubman's TT where, though outclassed, they performed with distinction. One of the trio, Jack Hill, finished in 32nd place at 66.39mph, whilst Franz Pados on a works-entered machine finished 16th, at an average speed of 70.28mph, just missing a free entry for that year's Manx Grand Prix.

One of the greatest accomplishments of the Sports Model occurred when Don Chapman, of the London Douglas MCC, entered one of these models in the 350cc Race at 'Motor Cycling's Silverstone Saturday Meeting' in 1950. Despite the fact that a number of the new 90 Plus Models had been entered in the same race, Don and his Sports Model had assumed a commanding lead by half distance, to continue to win, relegating R.A. Smith and his Gold Star BSA to second place. To prove that even the standard Mark III models were no slouches either, a team of three had been entered by the London Douglas MCC in the 1949 Junior Clubman's TT where, though outclassed, they performed with distinction. One of the trio, Jack Hill, finished in 32nd place at 66.39mph, whilst Franz Pados on a works-entered machine finished 16th, at an average speed of 70.28mph, just missing a free entry for that year's Manx Grand Prix.

As far as is known, no other motorcycle manufacturer took up torsion bar rear suspension, although a good many years later, Honda employed short torsion bars in place of valve springs on their CB450 model.

Whatever may be said about torsion bar rear suspension, it permitted the Douglas works testers to perform their party piece on a number of occasions. It was good enough to permit them to ride up and down a 4 inch kerb at 30mph, which would still be regarded as no mean accomplishment with today's systems. ![]()

See also When was it that? contents