Sometimes the urge to travel far and wide presents itself quite spontaneously, as was the case when Robert Edison Fulton Junior came to the end of a year's study at the University of Vienna's School of Architecture in 1932. As his name suggests, he was a young American graduate, whose parents were well-known in the USA through their involvement with airlines, railways and long distance coaches. It was whilst he was discussing his plans for returning home with his fellow graduates that he startled them all by saying he would do so by motorcycle, following a route that would take him around the world on the way. In all probability it was only a spur of the moment statement, but the more he thought about it, the more the idea appealed. When his parents got to hear of his plans they were aghast and immediately offered to fund his return home in comfort, all expenses paid. Although he remained resolute in his intentions, they frequently sent him telegrams whenever they knew of his whereabouts, pleading with him to ditch his bike and get aboard a boat at the nearest port.

His first move was to acquire a motorcycle, in the hope he could find a manufacturer who would sponsor him. His first call was to Harley-Davidson, who had a London Office in Newman Street.

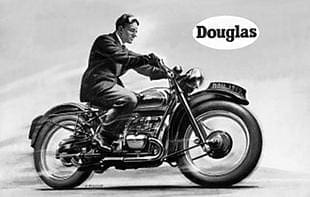

Politely but firmly they showed him the door. Fortunately, Douglas had their London Depot only a few doors away, so he called there next. As luck would have it Eddy Withers of the parent company in Bristol happened to be there at the time. After discussing his caller's proposition in some detail Eddy realised his intentions were sincere, so he suggested they adjourned to Bertorelli's restaurant to have lunch and sort out some of the finer details.

A visit to the Douglas works in Kingswood, Bristol, followed soon afterwards, when it was agreed a new 600cc model T6 Douglas and sidecar would be provided free of charge. It was a surprisingly generous offer because at that time the company was facing what proved to be the first of many financial crises that threatened its very existence.

To cope with such a long journey the machine needed to be specially prepared. An extra slab-sided petrol tank was fitted behind the saddle, which carried an additional four Imperial gallons to supplement the three gallon capacity of the machine's normal petrol tank. Two other containers were arranged either side of the rear wheel, to contain a comprehensive tool kit. Another box shaped container attached to the rear of the auxiliary fuel tank held 4,000 feet of cine film A luggage rack mounted over the front wheel, fitted with a leather bag, contained a cine camera and various items of clothing including the inevitable toothbrush. Above this was a windscreen with a special leather pocket for holding maps. Not so evident was a tray under the sump of the engine that concealed his sole means of protection, a .32 Smith & Wesson revolver. Both tyres were oversize and a spare wheel complete with tyre, brake drum and sprocket was attached to the rear of the sidecar. Quite by coincidence the engine number was RF69, his initials, and the registration number GF 1616, easy to remember as the numbers added up to lucky sevens.

According to plan

Robert's journey around the world went according to plan, although it nearly came to an end as he passed through France soon after he had started out. His sidecar was written off as the result of a traffic accident, so its remains were detached and from then on the Douglas was ridden solo. He eventually arrived home after covering 40,000 miles in seventeen months. Amazingly, he had suffered only six punctures in total, all of them in the rear tyre, hardly surprising as the overall weight of the machine plus what it was carrying was close to 7501bs. The front tyre never left its wheel rim. Only once did he run out of petrol, just outside Munich. As luck would have it he had only a kilometre's walk to the nearest filling station.

Many years later a detailed and well-illustrated account of his epic journey was published in the form of a book entitled One Man Caravan, of which a few copies can sometimes be found at auto-jumbles. Now a collectors' item and with a cover price to reflect this, it is still of all consuming interest to Douglas owners. It was published by George C. Harrap and Co. Ltd., in 1938 and runs to 272 pages. Written with a certain amount of author's licence it fails to mention the sidecar incident and gives the impression it had always been a bike only journey. Fortunately, a photograph of GY 1616 with its sidecar attached was published several years ago in the Western Daily Press to dispel this illusion.

After the publication of his book Robert Fulton Junior more or less passed into obscurity as far as this country was concerned until some enquiries about his round the world journey were published in New Con Rod, the bi-monthly magazine of the London Douglas MCC. Then, almost as if by magic, a letter from Robert himself arrived to say he intended visiting the UK during early 1991. Now 80 years old he hoped to take a brief look at Bristol as part of his itinerary, so members of the Bristol Section of the London Douglas Club made arrangements to act as his host to make his visit to the city all the more enjoyable. Foremost amongst them was the late Eric Brockway, a former Managing Director of Douglas, who made sure he visited some of the city's more historic sights. During one of their conversations he was most surprised to learn that not only had Robert brought with him a video made from his original cine film but also that he still had his Douglas, which had been partly restored in the USA.

Fully restored

Before he departed, Robert dropped yet another bombshell. He would like to have his Douglas fully restored. If he shipped it to the UK, could someone be found to oblige? It was all too good to believe, so a small group of London Douglas Club members agreed to handle the restoration themselves, each person to be allocated a job where their specialist knowledge would be put to good use. In due course the machine was shipped to Don Brown, who had built the quite unique four cylinder 'special', the 700cc Douglas Dragon Four, in his home workshop. It arrived in the UK during the middle of August 1991, only to be retained by HM Customs and Excise for much longer than expected. They had to be convinced it had been imported only temporarily and was to be returned to the USA, before they would release it. Eventually it was delivered to Don's home in Charfield, Gloucestershire, where a small group of Douglas enthusiasts gathered on the morning of Saturday October 26 to witness the opening of the packing case that contained it. No one knew what to expect so it was with relief that the old machine was found to be in much better condition than had been anticipated, and was complete with all its original fittings.

The only evident damage was a dent in the exhaust pipe, which could well have happened before the machine was crated up. If anything, the only disappointment was that the machine was no longer in its original colours. It had been painted a pearlescent steel grey, similar to one of the alternative colour schemes of the S8 Sunbeam.

The old Douglas still proudly bore its original front number plate, but of necessity an American license plate was fitted to its rear as it had been used there on the road. It also had an American headlamp and tail lamp, to comply with the different lighting regulations in the USA. Although an American speedometer had been fitted, thoughtfully the original Smiths instrument had been included, sadly now re-set to zero.

The old Douglas still proudly bore its original front number plate, but of necessity an American license plate was fitted to its rear as it had been used there on the road. It also had an American headlamp and tail lamp, to comply with the different lighting regulations in the USA. Although an American speedometer had been fitted, thoughtfully the original Smiths instrument had been included, sadly now re-set to zero.

The restoration work went ahead as planned and towards the end of May 1993 the Douglas had been restored to its former glory and was ready for Robert to collect. On May 29, representatives from the local newspapers, local radio and TV, and members of the London Douglas MCC gathered outside the old Douglas works to witness Robert being presented with his rejuvenated Douglas. Now in his 83rd year he enjoyed every minute of the occasion and looked as though he was about to ride off on it into the sunset. He must have found it difficult to believe that some 60 years earlier he had set off on the same machine, not knowing what lay ahead of him on his long journey back to his home… ![]()

See also When was it that? contents