The history of motorcycling is littered with ‘what might have beens’. John Milton takes a look at one of the more unusual of those.

While the name of Vincent conjures up visions of legendary machines still revered to this day, less well-known is the Stevenage company’s foray on to three wheels. Or, to be precise, ‘forays’, for it happened not once, but twice.

In 1932 Vincent introduced the Bantam some 16 years before the Birmingham Small Arms Company would introduce its widely successful model of the same name. In fact, the Vincent model has faded so far into the background of history that few people even realise that there was a Bantam of another feather.

Enjoy more Old Bike Mart reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

The Vincent Bantam was a three-wheeled machine which was powered by a 293cc side-valve JAP or a 250cc Villiers engine. It weighed in at 2.5cwt and was fitted with a car seat and steering wheel and was aimed at the delivery and trade market. At this time, with just a £4 road fund licence (half that of a conventional van), it was far cheaper for a tradesman to both buy and use a three-wheeler, not to mention the fact that it could be driven by a 16-year-old.

Initially priced at £49, it was cheaper than competitors such as the James Handyvan or the Raleigh Carryall (although a windscreen and a hood was an extra £5 10s) but was – as the name might suggest – a more lightweight machine than those rivals. In 1932, the Raleigh Carryall van, at twice the weight and twice the horsepower, was more than £20 more expensive.

Perhaps because they were designed to be a workhorse, very few if any Vincent Bantams exist, despite a four-year production run, ending in 1936. Twenty years later, Vincent would once again venture into the three-wheeled world, but with a very different machine.

Building a sports three-wheeler

In the early 1950s, realising that the post-war boom in motorcycle sales was inevitably decreasing, Philip Vincent turned his thoughts to capitalising upon the Rapide by way of using the parts of that motorcycle in another form. He said: “I decided to set about building a sports three-wheeler, embodying the Rapide engine with the minimum modifications possible.”

Although he had the constituent parts in mind – an independently sprung front axle with rack and pinion steering, hydraulic car-type brakes and a rear wheel using a standard Vincent suspension assembly – Philip Vincent turned to Dick Shattock at RGS Atalanta to create the bodywork.

This was a company which had a history reaching back to the 1930s. Prior to the Second World War, one Alfred Gough had worked for Frazer Nash. A brilliant engineer, he had designed a sophisticated overhead camshaft engine which, while acknowledged to be a remarkable piece of work, suffered from reliability problems due to Frazer Nash’s lack of budget.

Frustrated by this, Gough left – with his engine design – to set up his own company. With backing from racing driver Peter Whitehead and Burma Oils heir Neil Watson, Gough unveiled the Atalanta in 1937 and it was immediately hailed as one of the most advanced cars of the time. It boasted features such as fully independent coil spring suspension on all four corners, adjustable damping front and rear, hydraulic brakes all around and an electric operated pre-selector gearbox, made of cutting-edge materials such as duralumin and hiduminium.

Just 20 cars were built before the company closed down car production in 1939, heavily in debt, and moved into making pumps as Atalanta Engineering.

As advanced as the Atalanta was (a later version featured the V12 engine from an American Lincoln Zephyr), buyers were unprepared to pay the asking price which was almost twice as much as a contemporary Jaguar SS100.

In 1949 Richard Gaylord ‘Dick’ Shattock, a chap who had previously built his own racing special using an original Atalanta chassis, bought Atalanta’s remaining stock of parts to provide an aftersales service for owners of the company’s pre-war cars.

Having also acquired the rights to the Atalanta name, he attached his initials and built around a dozen RGS Atalantas, although more were constructed by owners who bought his kits which would eventually offer glass fibre bodies in the newly available wonder material.

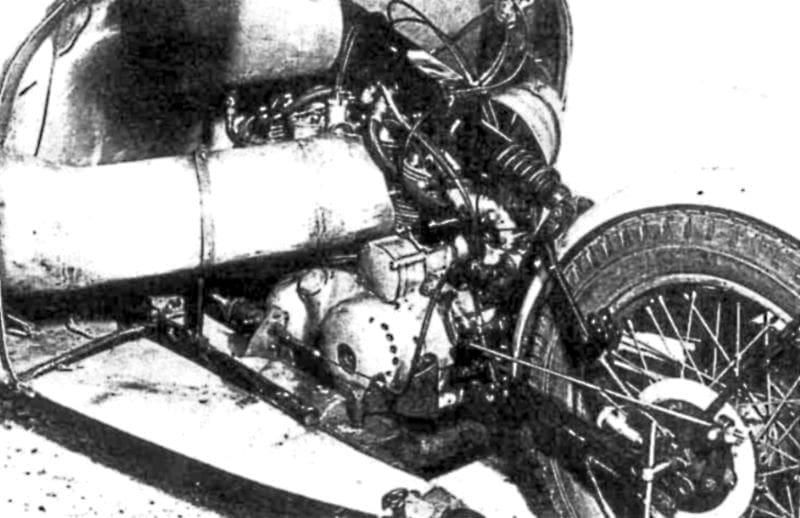

Like the plans Vincent had for a three-wheeler, the RGS Atalanta had a tubular steel chassis and an independent suspension set-up, so Vincent tasked Dick Shattock with the job of creating the bodywork for its new project. This Shattock did, making the body from hand-beaten 16-gauge aluminium.

An exciting maiden road test

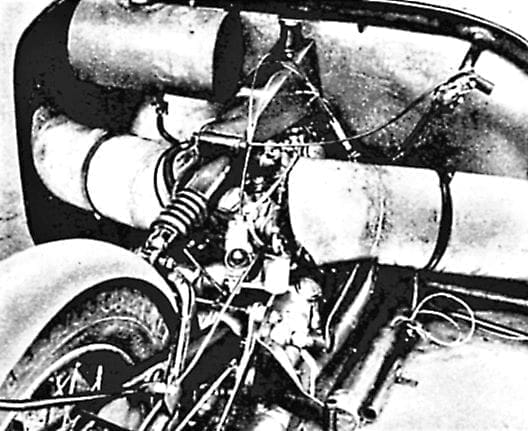

The engine was initially a standard 998cc Rapide motor, rubber mounted behind the seats, and which was cooled via the gap at the front of the car which flowed air straight on to the front cylinder and by two side air vents. A two-gallon petrol tank was fitted on the bulkhead and, above the engine was a Rapide Series C oil tank which acted as a frame member for the Series D Armstrong rear spring. The chassis was constructed from four-inch tubular steel; at the front, in the interests of economy, were two 14-inch Morris Minor wheels and at the rear an 18-inch wheel fitted with an Avon sidecar tyre. (This, Vincent’s chief tester and development engineer, Ted Davis, would admit was “totally inadequate, especially on wet roads.”)

The first road test of the three-wheeler was, by all accounts, somewhat exciting. A company mechanic who had been working on the car was enlisted to take the vehicle for a drive up the Great North Road. After a push start, he set off at a rapid rate of knots and return at a similar speed, careering through the factory gates and removing a drainpipe before finally stopping. It only transpired then that the mechanic had never driven a car before, but he did report that, although he found the pedals a bit confusing, he had thoroughly enjoyed his first ride in a car!

Now perhaps a little more cautious about to whom the prototype was entrusted, the directors handed the three-wheeler over to Ted Davis to further hone the project. Davis was well-known for his ability on three wheels, albeit in motorcycle outfit form, and had also been one of the team of Vincent riders which had taken eight new records in Montlhéry in France in May 1952.

It must be said that Davis was not above frightening his passengers with the three-wheeler, as he recounted: “Paul Richardson, then technical services manager of Vincent [was a passenger] who shared in a somewhat alarming incident when the steering wheel came completely adrift whilst we were doing some 90mph along the Great North Road (near Stevenage); fortunately, we were able to brake to a standstill without further incident.”

“The wind pressed our cheeks against our face bones”

Ted Davis was clearly not a man to hold back even with a passenger on board, as Bruce Main-Smith discovered when testing the prototype for Motor Cycling. Curiously, his report didn’t appear until the end of 1956 by which time Vincent had ceased motorcycle manufacture and was heading towards receivership. He wrote: “With Ted Davis at the controls … the Smiths speedometer read 60mph; time to change up. A gentle pull on the gear change lever on the driver’s right and the next cog was in; round the needle moved again. 75mph – scuttling and still picking up – 80 on the clock, then Davis changed up again… the wind pressed our cheeks against our face bones as 90mph came up…”

Ah, the days when the public highway was a test track for motorcycles and cars! Davis later wrote of an incident when he was testing the three-wheeler on the A5. “A group of Vincent Motorcycle Club members [were] heading North to the annual rally who, at that time, normally expected to be ‘Kings of the Road’ and usually were, when they came across what was to them probably another abortive Villiers or Excelsior two-stroke powered economy three-wheeler. Somewhat surprised to find it doing 60mph plus, they immediately roared past, only to be repassed at 70 plus; with no more ado they opened the taps to near full chat and repassed, only to be repassed again; by this time 100mph plus was showing on everyone’s clocks.

“The faster men of the group on their Black Shadows were really getting ‘steamed up’ now and had dropped into semi-racing riding positions. The sight of half a dozen Vincent Black Shadows apparently escorting this strange looking device from outer space, all doing well over 100mph, must have provided a local farmer, just cautiously creeping across the road with his tractor, quite a talking point for the pub that night. When the group of Vincent riders eventually saw the power unit in the little silver car, all was forgiven.”

Of driving the little Vincent, Bruce Main-Smith commented: “Straight ahead progress at high speed demands real knack – knack that I didn’t acquire on such limited acquaintance for, I was told, there is a tendency with [the] highly geared steering to overcorrect and until a driver has covered several hundred miles he doesn’t feel too much at home.” He did add that he also had ‘a slightly apprehensive Davis’ beside him!

Although this is mere speculation, it would appear that when Bruce Main-Smith was granted his test drive, the three-wheeler was still fitted with a standard Rapide engine for he commented that, with now down gradient, they were unable to ‘crack the ton’ and, when he was eventually allowed to get behind the wheel he refers to the “most detuned version of the 1000s that Vincent ever made”.

Fitting the engine from ‘Gunga Din’

But Ted Davis always felt that, with a more powerful version of the V-twin, the three-wheeler was capable of much, much more and he was finally able to prove this by installing the engine from the famous Vincent development test bike, ‘Gunga Din’. He did say: “At a top speed approaching 120mph, straight line stability, like the fast cornering, was bordering on the alarming” and that really 70bhp should be kept for four wheels. Eventually, while racing at Snetterton in 1956, Davis blew up the engine of the three-wheeler so comprehensively that only the heads could be salvaged.

That, allied with the closure of Vincent, seemed to be the end of the road for the three-wheeler. While it was indeed a futuristic machine, it was surprisingly heavy at 9½cwt (when the Mini was introduced in 1959 it would weigh just two hundredweight more), although no doubt a glass fibre body would have lowered that figure. But when the prototype was offered for sale, it had a price tag of £500 – which, again to compare it against that ubiquitous car, was more expensive than the slightly later Mini and the same price as a contemporary Morris Minor. It didn’t have a reverse gear and to start the engine (if there was no handy steep hill available) involved removing a panel on the driver’s side of the car and kicking over the engine – without the aid of decompressors.

The three-wheeler languished at the Stevenage factory and in 1958, Ted Davis wrote to a gentleman who had been considering making a replica to tell him that the actual three-wheeler itself was for sale and could be his for £275. It had cost more than £2000 to build.

It appears that the recipient of the letter, a Mr Broughton, was not interested, for the three-wheeler was still in residence when the company was taken over by Harpers in 1959. Then it was sold although, for reasons unknown, it was later returned.

Rescue comes at last

Finally, it was bought by Josef Karosek, a former German prisoner-of-war who had settled in Britain and married a lady farmer. He read about the car in a magazine and contacted Harpers to see if it was still available. It was, and £100 later he had rescued the three-wheeler which would doubtlessly else have been broken up or fallen derelict.

Joe Karosek hired a car restoration company in Sussex near his home to restore it and paint the bodywork in British Racing Green. He then used it on the road and also raced it at various circuits. He also had fitted an outrider shaft extending from the original kick-start shaft which enabled the driver to kick-start the three-wheeler while standing alongside it. However, after a while, it appeared that he stopped using it and the little car became very careworn. Finally, it was purchased by Vincent historian and author Roy Harper, who had wanted to own it since first seeing the three-wheeler in 1955 – a time when he was doing his National Service and thus not in a financial position to offer the £500 that Vincent then wanted.

Finally gifted a name by Harper, ‘Polyphemus’ was restored to its former glory. It currently belongs to Vincent specialist Bob Culver. But the Vincent three-wheeler really is a case of ‘what might have been’. We will leave the last words to Bruce Main-Smith, who wrote in 1956: “I could enthuse about [the Vincent] for pages… The only real drawback, I imagine, would be getting through the crowds to it after leaving it parked for a while!”