A new documentary follows the life and career of legendary motorcycle designer Philip Vincent, told by the people who were there. Alex Bestwick speaks to director David Lancaster about bringing the Vincent story to the screen.

David Lancaster grew up around Vincent motorcycles. “My parents toured Europe on their Vincent, my father did the same up until he passed away in 1990, so I’ve always known Vincents and been around them,” he tells me as we chat about his new documentary Speed is Expensive, which explores the life of legendary motorcycle designer Philip Vincent.

The documentary will be available to buy as a DVD and digital release on September 25th .

Vincent’s story has always been of interest to David. “He started off essentially very wealthy, from a very privileged background I guess you could say, but having made these wonderful motorcycles ended up pretty much in poverty, living in council accommodation.” In Feltham, in fact, not too far from where David lives now. What’s more, David’s father knew both Philip Vincent and Phil Irving.

The personal touch can be felt throughout the film, which is not just about the bikes, but also the people who made them. “Even at the early stages, we wanted it to be a story about human endeavour as much as the motorcycle itself,” says David.

Philip Vincent’s family worked closely with David and co-producer Gerry Jenkinson, including sharing home film shot by Vincent himself. It was also important to David to hear the stories of the men and women who worked on the shop floor.

“We thought it was a good way to tell the story of a machine through the humans who built the machine. We also wanted to get the voices from the shop floor as much as the two Phils, Phil Irving and Phil Vincent – both brilliant, driven, possibly you could say geniuses, but of course it takes a lot of people to build and design a motorcycle.”

The making of the documentary was clearly as much of a team effort as building Vincents, and David regularly makes references to the team behind the scenes throughout our conversation. “A lot of the people who helped with the film had come in because their passion is Vincents,” he tells me.

This passion comes through in every aspect of the documentary. Vincent motorcycles were relatively short-lived, yet have an enduring legacy. I asked David more about why he thinks this is, and the making of the documentary:

Why do you think it is that we’re still talking about Vincents today?

Vincent had a genius for design, but he was also a marketing genius. He gave them these really cool names: the Black Shadow, the Grey Flash. It certainly captured some people’s imagination. But also they are really good motorcycles, and if you ride a Vincent today, you can still ride along with traffic, you can sit on the motorway at 75mph, certainly the V twins, the 1000s. There’s not many British bikes – I’ll probably upset a load of people – but really only a Norton Commando could do that sort of long distance, 2 or 3 hundred miles a day. I mean stuff goes wrong with them, because they’re 70 years old…

Also, I think they’re just objects of beauty. Every time I see one I still think it’s the most beautiful motorcycle engine. I just think the flow of the exhaust, the way the two cylinders sit at the perfect 50-degree angle… And they’re fun to ride. For the time, they must have been amazing. The Series B Rapide came out in 1946 and the country had just won the war. The phrase is ‘they lost the peace’ because rationing endured until the early 50s, food, petrol. So I just admire the ambition of Vincent and Irving to launch a 110mph motorcycle into a country that was really on its last legs, everything tired and worn out, including the people. Most manufacturers put a lick of paint on a pre-war model and they carried on roughly as they were. Vincent came out with a completely new design – obviously the Series A V-twin was just before the war, but there were only 78 or so made.

You’ve just got to admire the vision that they thought ‘this is what the world needs. It doesn’t need a plodding, go-to-work 350. It needs a 1000cc motorcycle that costs a lot of money and does over 100mph’. I think the world needs people like that.

So what went wrong for Vincent?

The more people we spoke to, the more it emerged there was this pivotal motorcycle accident which he had in the winter of 1947, which was a really bad winter in terms of weather. He fell off testing a Rapide at about 80 mph without a crash helmet. As I think perhaps generations post-war were prone to do, it was rather ‘well, I lost my sense of balance and took a couple of months off…but brush yourself down and press on’ but it turned out he was in a coma for quite a while. So the more people we spoke to, particularly John Surtees, said there was a personality change, that he wasn’t quite the gregarious evangelist for his motorcycles, he became a bit more withdrawn; less collegiate.

Then Phil Irving left a year or so later, and the later models were quite controversial, as you may know, the enclosed models with the fairings. So you could see this peak of engineering and design with Phil Irving and Phil Vincent working together, in some ways it didn’t actually last that long, and the factory stopped producing bikes at the very end of 1955. They produced more motorcycles than people think, 11,000 were produced.

Then talking to Philip Vincent’s daughter and his grandson Phil, who’s quite a big part of the film, we began to look at his later career, which was really one of frustration. He never got another vehicle put into production, but he had this amazing creative mind and he was always thinking of things. He developed a rotary engine which seemed to have a lot of potential but he couldn’t quite raise the money to get it put into production or get a larger manufacturer interested. And rotary engines are really interesting, but Mazda have sort of ploughed their own furrow, there aren’t that many on the market, there’s been a couple of motorcycle ones, the Suzuki RE5… But because Vincent could complicate his designs, it was a complicated rotary engine, and he wanted it to be made out of ceramics.

Anyway, this was all quite sad. At first, on leaving his own company, he ran a garage in Lincolnshire, then they moved to London and he did some constultancy work for British Rail, he did some journalism, but essentially his creative life peaked in the late 40s and 50s. Then after a series of strokes they moved to this council flat out in Feltham, which is quite near me, because he couldn’t get up the stairs in the flat they were in.

It was quite sad, and I thought this is really interesting. Then in 2018 – so we’d been working on the film for a good while – a Black Lightning, which was the Australian land speed record machine, sold at Bonhams for 1.2 million Australian dollars. I started, as you’re constantly doing on a documentary, trying to join the dots: that Vincent died in ’79 pretty much penniless, and here we are 30 odd years later and one of his machines has become the most expensive motorcycle ever sold.

Ewan McGregor narrates the documentary. How did that come about?

During lockdown, our American producer, James Salter, who’d been on board since the early days, said ‘I think I’ve found a way that we can put this project in front of Ewan McGregor.’ Which he did, and then because the emails went in to my SPAM folder, I just got a phone call from Ewan McGregor at about three in the afternoon, completely out of the blue, because I hadn’t checked the emails.

He said, ‘this sounds great, I’d love to be involved.’ It was one of those phone calls where you stand up to answer the phone and go, ‘oh, it’s Ewan McGregor.’ And I said, ‘the script’s all ready’ but of course it wasn’t quite.

He said, ‘send me the script next week’, so Gerry Jenkinson and I spent a very intensive period doing the voiceover script. I’d done items on television and written items for TV, but it’s really different when you’ve got this longer form narrative. It’s kind of like writing a novel. Anyway, luckily he liked the script – he wasn’t going to do it if he didn’t like it, I think that was pretty obvious.

Then a week or so later he recorded the voiceover from his home studio, and James Salter, our American producer, was in the recording studio in Los Angeles and I was in West London on FaceTime video, directing Ewan McGregor, which was the most bizarre experience of my life.

Did you have to narrow down what you could fit into the documentary?

Inevitably. There’s so much that we had to leave out. I sort of regretted what we left out, but you really have to focus on the story. One guy said to us, ‘I would have thought you’d done more about the pre-war Vincents’. Obviously, they’re in the film, but I think he still had the idea that it was going to be a model guide to Vincent motorcycles with some talking heads and I tried to say, ‘no, we want to tell the story of this man and Phil Irving.’ So in the DVD that’s coming out there’s an hour of extra content, and then we’ve got loads of other content as well. But after a while you have to focus on getting the film released, you’ve got to go through the Film Censors Board, get certification. There’s so much involved, you can’t keep going back and looking at what you could have done or what you left out.

Vincent bikes broke a lot of world records – which to you is the most iconic?

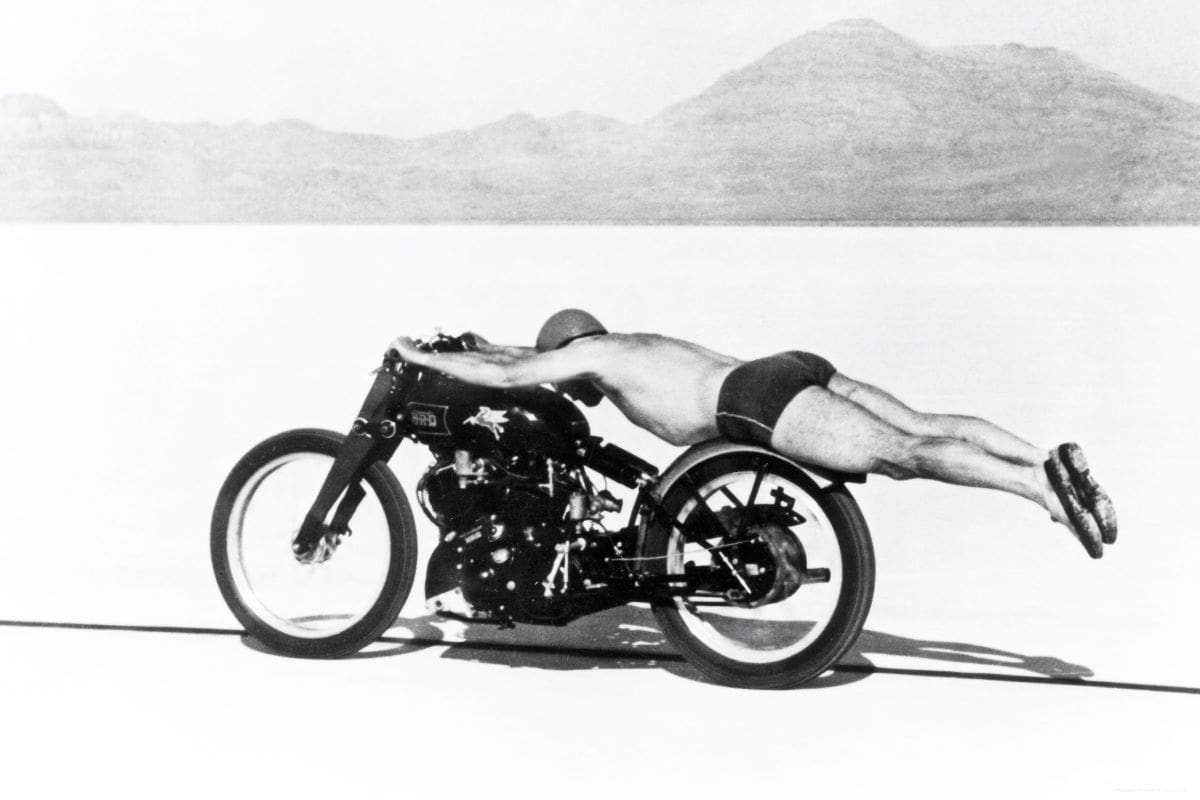

They’re all great because going those sorts of speeds on motorcycles, it’s really difficult, you really have to hang on. But the most iconic one is the Rollie Free record bike, as you saw in the film. We didn’t know there was actually cinefilm of the event until the chap who owned the bike let us know about this. So as some people know, he got very near to getting to 150 mph on a Black Lightning prototype at Bonneville Salt Flats, but he decided his leathers, which had been ripped a week or two before, were flapping around. So he decided to do the runs basically in swimming trunks and a pair of trainers. And you think ‘what on earth is going on in that guy’s head?’ Lots of motorcycle fatalities, they can very often be infections of the skin rather than broken bones, so if he’d have come off at any sort of speed on salt, he would have died almost immediately or he certainly would have been in danger of losing his life because your skin is your biggest organ, isn’t it? So the bravery of the guy, the foolishness… I mean that’s what I wrote in the script, nobody had done more before or since or was more committed to a record than Rollie Free on that afternoon. And I was lucky to meet him years later, he was at a Vincent rally in Canada and he was great fun, he was really interesting. I was only 11 or 12, but I sat and listened to him talk about these adventures, and you just think ‘wow’. Even at that age, I thought, ‘this is amazing.’

What impact have Vincents had on the motorcycle scene?

I think they do have an enduring legacy, because if someone sees one, it’s evidently more than an old bike. I think anyone who is interested in vehicles in any way, not in any deep way, you just look at it, and I see this when I’m out on my bike, people do turn their heads and they do with lots of old vehicles. So I guess there’s a sense in which is it the ultimate classic bike? I think it probably is. Because of the performance, because of the individual endeavour. It wasn’t designed by a committee, it was designed by Phil Irving and Phil Vincent, and they pushed through a motorcycle that BSA or Triumph just would never have put into production with. They would have said ‘we don’t need to do that, the market doesn’t need it’ whereas Vincent and Irving were of the opinion ‘we’ll build the best motorcycle possible and we’ll find some buyers afterwards.’

John Surtees makes the point that he worked for Vincent and that was his first job, and then he drove for Honda and he drove for Ferrari and he rode for MV Agusta. So it occurred to me, where does Vincent come in that pantheon? And it was great, John Surtees said, ‘well, he’s up there with those pioneers.’

Even though one could speculate on the value and the prices of these things, the fact that they’re still sought after and they still sell for 30, 40 thousand pounds for a basic model, is sort of testament. And that’s the same with Ferraris and MV Agustas and all of those stand-out manufacturers, many of which haven’t lasted. Bugatti would be another example, and Bugatti possibly is a closer parallel to Vincent because these were driven individuals and both of them wanted to make the best vehicle for the road, which was different with Ferrari who was obsessed with racing and to a degree MV Agusta.

If you could own or ride any Vincent, which would it be?

Well, I really like the one I’ve got, because it was my parents’ bike in the 50s and I tracked it down. That’s a very early post-war bike, a 1947 bike.

The Grey Flash is a really interesting model, it’s the racing 500cc. There’s not many of those; about 30. I’ve always liked those, and they were built with this very beautiful palette of grey. As I say, Vincent was great, he would give them these kind of Boy Own names: Grey Flash, Black Knight. They’re all nice, actually. All Vincents have got something going for them. The later ones, the enclosed ones, are very comfortable, they’re very good in the rain. They’re not light and nimble motorcycles, but they’re what my dad had for the last 30 years of his life, which he really loved because he just liked to sit on a bike, go long distance, and it was a bit like being in a Rolls Royce, just cruise along.

You mentioned tracking down your parents’ Vincent. What’s the story there?

The Vincent Owners Club have access to the factory records and I’d been asking my mother about it after my father died and she said, ‘oh, I don’t know what the engine number was or anything’ and then I found the registration in a picture. And I did find the engine number, it was a bit of detective work, in an old handbook of my father’s. So I looked at the engine number and I thought ‘oh, maybe that’s the Rapide which they used in the 50s.’ And then I got through to the registrar at the Vincent Owners Club and he very kindly said, ‘I think the bike’s in Germany.’ He wrote to the owner. I went to see the bike, it was in a museum.

Then it came up for auction at Bonhams, and I managed to raise the money in order to buy it. I sold a couple of other things, but I’m very glad I did because it’s a bike that means a lot to the family, and it’s also one of my favourite models, the early post-war Rapides. In some ways, they’re the purest example of it because that’s what they launched in 1946 and, like most automotive trajectories, the bikes got heavier and taller and the early Rapides are quite nice and quite low and a bit old-fashioned, but it’s an old bike. I don’t see the point in changing this and changing that, you might as well go and buy a ten year old BMW if you’re going to do that.

Are there any other stories in the motorcycle world you want to tell?

I think there are. I’ve started another documentary – foolishly – but it’s not about motorcycles, it’s about a food writer. I mean there are some great stories in motorcycling. Joey Dunlop lived an interesting life, multi-TT winner. At the Bonneville Salt Flats every year there’s some very compelling people building their own bikes and going at 2 or 3 hundred miles an hour, they’re really interesting.

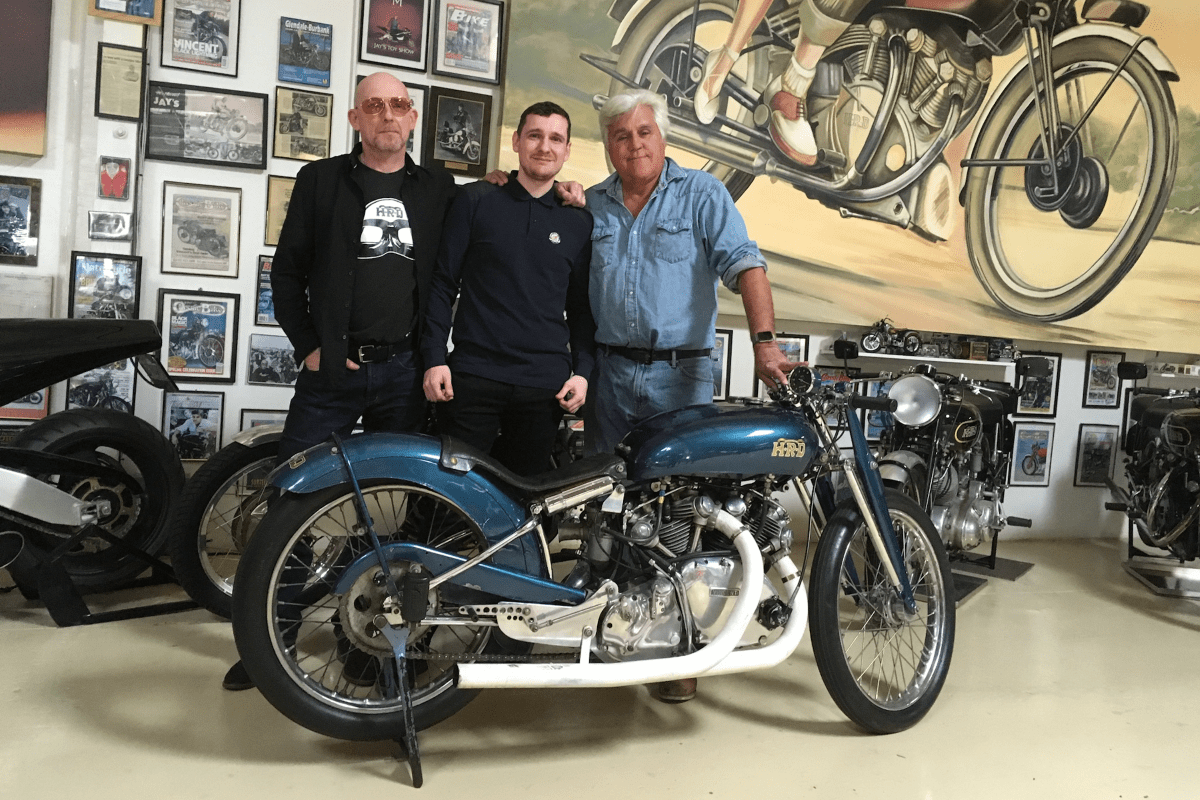

I think like all of these things, the vehicle is what runs through the film, but the human stories behind the vehicle, that’s where the interest is. Somebody giving up a job to build something or sacrificing nearly everything – sacrifice is always quite an interesting human endeavour, and Vincent made sacrifices. He could have worked for a big automotive manufacturer, but he went his own way. He never really worked for anybody, Vincent. He had his own motorcycle manufacturer at the age of 18 or 19, and maybe that was his downfall. Maybe 6 or 7 years working at Triumph or Norton would have taught him more about costing and building something to a budget. But as Jay Leno says in the film, the legacy is the fact that they didn’t have bean counters all over the motorcycles, especially in the early post-war years, and this is to our benefit. The bikes were built to be as good as they could be rather than built down to a cost.

Where can our readers watch the documentary?

The documentary will be available to buy on DVD and Digital Download from September 25. That’s got a 24-page booklet with some of the interviews we’ve done, some extra information. Also there’s an hour’s extra content, which is all good stuff, it’s more interviews with the factory people, extra footage of Jay Leno who talks brilliantly about the bikes more on US racer Marty Dickerson and the US-drag bike, The Barn Job.

On the same date, it will be on digital download, which will be on Apple, Virgin, Amazon. More news to come soon too on other activities – keep an eye on our Facebook and Instagram accounts, and main website www.speedisexpensive.com

Anything else to add?

There’s a lot people who helped make the film happen. Our financial supporters have been wonderful. They’ve supported us, they’ve helped us with flights, they’ve helped us with filming, so I need to do a shout out to those people. A documentary like this, you really do it because you want to see the story told, and they’ve been as important a part as myself or Gerry our co-producer or Russell Icke and Liz Deegan, our brilliant editors. So thanks to the people like Kris, Harvey, Peter, Tim, Colin and others who supported us. Plus some stand-out moments and great people such as Peter Bender (owner of the world’s most expensive motorcycle) who transported the bike hundreds of miles across Australia, so we could film it back on the same road it set the Southern Hemisphere land speed record on, in Gunnadah, in 1953. With Peter, we managed to track down, and film, two elderly gents who watched Jack Ehret set the record, when they were young schoolboys, 70 years ago now.

Speed Is Expensive will be available on Digital Download from 25th September.

Pre-order your digital copy here and your Collector’s Edition DVD here.