One of this country’s most noted female trials and enduro riders, Olga Kevelos was, to put it mildly, quite a lady, as John Milton relates.

Enjoy more Old Bike Mart reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Olga Kevelos was born into an affluent Birmingham family on November 6, 1923, the daughter of a Greek father who worked on the Birmingham Stock Exchange and an English mother. Two subjects at which she excelled at grammar school were astronomy and metallurgy and, after school, the latter led her to a job at the laboratories of William Mills, manufacturers of the Mills Bomb. But she was soon offered a post at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich; however, this was now war time (Olga would later say she was grateful for the war, otherwise, she said, she might never have left home). She hadn’t taken up her new job long before air raids forced the observatory to close and the staff were evacuated to the Admiralty in Bath.

This didn’t suit Olga at all. She hated being mired in clerical work and her inability to do even the most basic mathematics frustrated her bosses. At some point in 1943, Olga saw an advertisement in The Times in which the Department for War Transport was seeking female trainees to man canal barges for the Inland Waterways. Desperate to get away from the dreariness of her everyday job, Olga applied and would spend the next two years with all-female crews ferrying vital war materials up and down the Grand Union Canal between the Midlands and London. The women wore badges bearing an IW insignia which officially stood for ‘Inland Waterways’, but which they nicknamed ‘Idle Women’, although they were anything but.

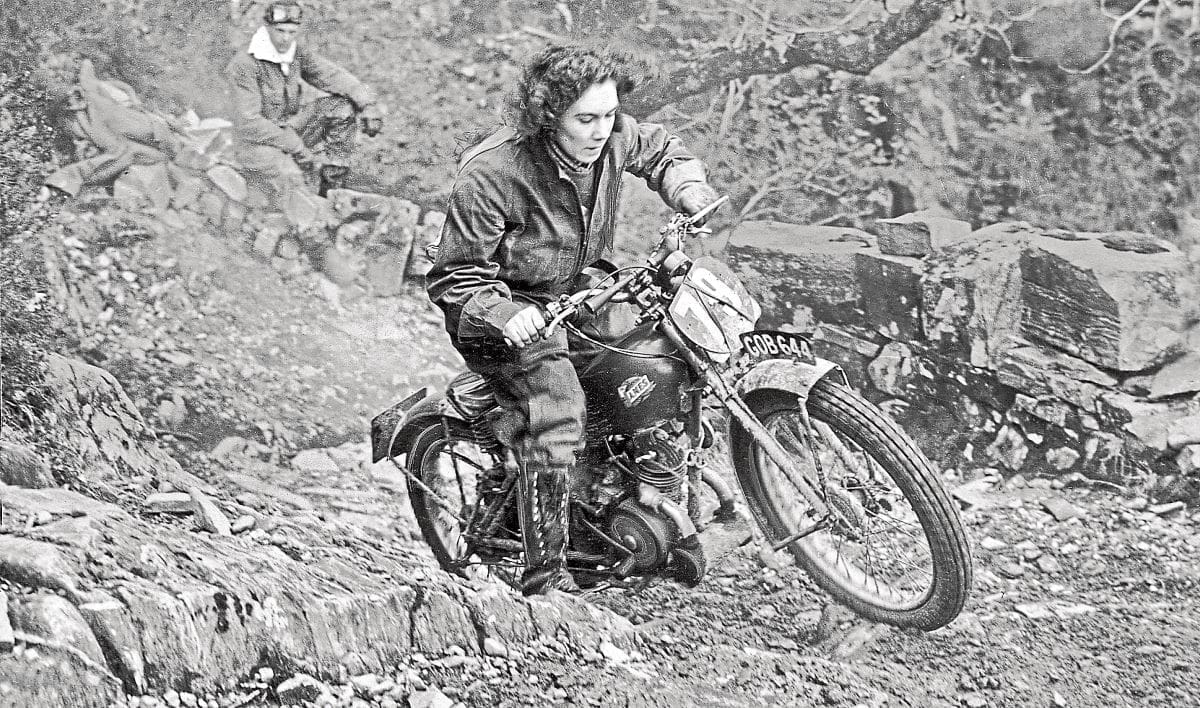

After the Second World War, Olga spent some time studying in Paris and then returned to Birmingham to help run her family’s Cherry Orchard Restaurant in Cherry Street. It was there she met and dated racer and restaurant regular Phil Heath. Heath was away racing so much that Olga decided if you can’t beat ’em, then join ’em, and at the age of 23 started to ride. At first she borrowed a motorcycle from a friend and then bought an ex-War Department Royal Enfield 350cc. Heath, a member of the Continental Circus, introduced her to the Solihull Motor Cycle Club. The president of the club was Arthur Kimberley, sales manager for the James Company which his father owned. He suggested she take up trials riding and provided her with a James 125cc. Olga proved her worth in her first events and she was then offered a James for the Scottish Six Days Trial.

Unfortunately, she failed to finished after the magneto failed on the James, but the experience was sufficiently satisfying to ensure she bought a 350cc AJS and set off for the 1949 International Six Days Trial which was being held in San Remo in north-western Italy. Unlike her fellow competitors who put their machines on the train or in works vans, Olga rode from the Midlands to the Italian Riviera with various adventures (adventure somehow always managed to find Olga!) along the way, which ended up in her arriving a day late. She still managed to make the weigh-in but her bike was then locked away with no chance for her to check it over.

Two days later she broke a wrist and an ankle in a crash with a car, but by then the crowds – and many of the competitors – were in love with her. Still with her limbs in plaster, she rode the Ajay back to England.

Just one of four women to compete in the 1949 ISDT, an article appeared under Olga’s byline in Motor Cycling magazine in August 1950. In it, she extolled the joys of trials riding, writing, “girls, this year is the golden opportunity to enter [the ISDT] and find out just how unique this trial of trials riding really is… you don’t need the strength or constitution of an ox to be able to ride. Disregard all the old wives’ tales about the horrible internal complications that occur to women who ride for sport. A girl of average physique, in good health, will find she has strength enough and will not harm herself.” Mind you, this was from a woman who had ridden halfway across Europe with two broken bones!

By the time the ISDT rolled around in 1950, Olga had acquired a 500cc Manx Norton and she subsequently won a Gold Medal. She is often cited as having won a second Gold Medal in 1953 on a CZ 125cc, but according to author Colin Turbett who wrote a biography of Olga, ‘Playing With The Boys’ (sadly currently out of print, if you ever see a second-hand copy do not hesitate to snap it up), that wasn’t so, even if she might have thought she deserved it.

Olga Kevelos was a very attractive woman and that, coupled with her sparkling personality and down-to-earth sense of humour, brought her much attention from the media, manufacturers and others in the same world. (Len Vale-Onslow’s son, Peter, reckoned that his father would do just about anything for Olga and, by many accounts, he was far from the only one.) But, however pretty a girl might be, motorcycle companies wouldn’t offer backing unless she could prove herself in competition. And Olga’s riding skills, not to mention her sheer bloody-mindedness and determination, led to backing from manufacturers and suppliers at home and abroad.

After riding a Parilla in the 1951 ISDT (during which she crashed, knocking out two of her teeth) Olga was then invited to Czechoslovakia by CZ; she would discover that its training regime was considerably more gruelling than any to which she had been used. She wasn’t allowed to go to a pub, riders had to be up at 6am to do a series of physical exercises after which they were expected to ride at least 200 miles over rough terrain. Then, in the evenings, they had to attend classes on how to strip down and rebuild their machines.

It seems that the Czech company was impressed with the lady from Birmingham. After the ISDT it gave her the motorcycle she had ridden in the ISDT, intending she use it in one-day trials. Olga reported that it wasn’t suitable for that and she was asked for her ideas and designs. Six months later two crates arrived for Olga, one a Jawa trails machine and one a CZ, built to her specifications. Olga was never shy of giving her opinion. When, as a works rider for the Essex firm in the late 1950s, Greeves lent her a machine, she reported back that it had promise but needed modifications. Bert Greeves was so incensed that he sent a telegram instructing her to send the bike back on the next train. A few months later, Greeves’ development engineer Brian Stonebridge had implemented all of Olga’s suggestions…

But Olga could turn her hand to four as well as two wheels, and on occasion in the early 1950s drove one of Cyril Kieft’s Manx-engined Formula Three cars. Kieft had asked Olga to join his Continental Formula Three team but this idea never got off the ground, possibly because Kieft was struggling to finance the racing operation. She went on to race another Manx Formula built by Rex McCandless, he of the Norton featherbed frame and with whom she was smitten. Like so many of Olga’s romances it seems to have come to naught and she never married.

In the late 1960s, Olga began to compete less and less although she continued to organise major trials and would take part in the Scottish Six Days Trial until 1966. She still took a keen interest in motorcycling and the riders she rated above all others were Sammy Miller, Ron Langston and the late Geoff Duke. She named those three because of their dedication and determination, qualities she both had and admired.

But now her life revolved around the village of King’s Sutton in Northamptonshire where, with her brother Ray, she ran the Three Tuns public house, served on the village parish council and ran her pub quiz teams with the same discipline she had experienced with the CZ team in 1953. In 1978 she took part in the BBC TV quiz programme, Mastermind, with her first specialist subject being Ghengis Khan. She made it to the second round where she answered questions on astronomy but didn’t go any further, although she would later appear on the Channel 4 general knowledge quiz, Fifteen To One. After she and Ray gave up the Three Tuns, she became involved in local politics, becoming vice-chairman of the parish council. One can imagine she would have been a formidable opponent.

Olga died on October 28, 2009 just short of her 87th birthday after suffering a massive stroke. It had been a remarkable life well lived.