We often hear the main Japanese manufacturers referred to as The Big Four, with the occasional oblique reference to Bridgestone acting in the role of George Martin as the fifth member of The Beatles.

Holding on to that Mop-Top analogy for a moment, Steve Cooper takes a peek at another Japanese company that’s often overlooked and could, arguably, be described as the Pete Best of the Japanese bike world.

Masashi Ito, founder of Marusho, got off to a good start in the world of internal combustion engines when he began an apprenticeship working with Soichiro Honda at the latter’s car repair business in the early 1930s.

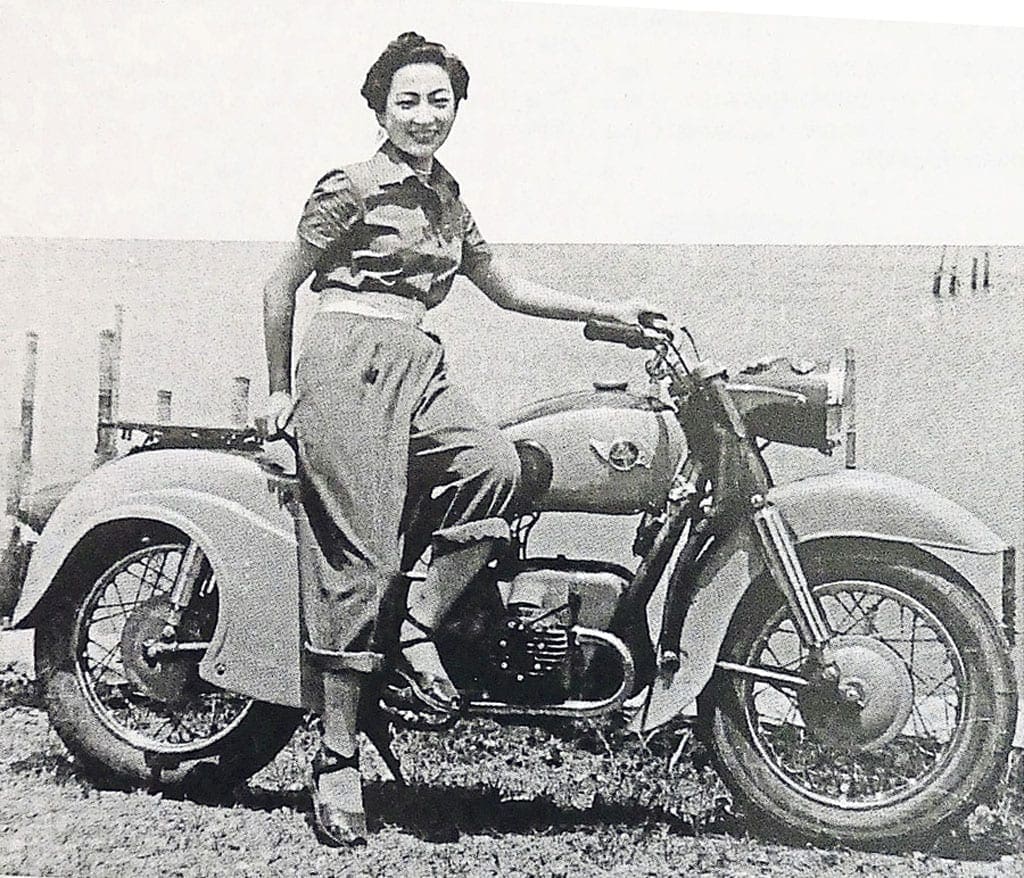

After the war, Ito and an older brother set up a car repair shop circa 1946 but, by 1950, Masashi Ito was making motorcycles loosely based around pre-war Zundapp singles. Variously named LB, ML and LC, most of the machines featured shaft drive, which would become something of a signature design on all future models.

Confusingly the brand name Marusho has historically often been swapped out for the rather odd title of Lilac as a marque name. The story goes that lilac was the favourite colour of Mrs Ito, so her husband opted to use it and probably gained some much-needed brownie points in the early, frantic days of his business venture…

The company’s progress was often chaotic, veering from feast to famine and back again. Quality control seems to have been a primary issue for production problems and sales successes, along with some occasionally very odd business decisions; one of the strangest has to be the scooter deal.

Industrial giant Mitsubishi Nippon Heavy Industries had moved into twowheeled transport and, initially at least, had done rather well with their Silver Pigeon scooters. However, as the 1960s loomed scooter sales nose-dived and, against logic and common sense, Marusho took on the Pigeon with a view to selling it as the Silver Pigeon Galepet.

It all went horribly wrong and left Marusho with debts and cash flow issues that almost closed the business. This was ultimately to become a recurrent theme with the company becoming a subcontractor to Honda in 1962, having to relaunch itself in 1963/64 before finally closing in 1968.

Ironically, many of Marusho’s designers and engineers moved on to Bridgestone, which would also close just three years later. Often perceived as little more than a dusty footnote in motorcycle history, the machines offered by the small firm deserve better recognition so we’ll have a quick look at some.

The 150cc Lilac ML/LB/LC, of 1950/1951/1952, utilised long stroke, sidevalve motors with two-speed transmissions, shaft drive, housed in chassis made of pressed steel; the styling was variously Gallic or Teutonic. The mid 1950s saw Lilac KD/KE/KH 150/200/250cc variants mostly carried in tubular steel chassis.

The engines by this period were mainly OHV units and, atypically for the time, were often over square bore/stroke arrangements. Plunger rear suspension and telescopic forks became standard features.

The Lilac SY 250 single proved to be something of a signature machine for the firm and ultimately ran for some six years. The general layout is said to have been influenced by BMW’s postwar singles and there is a definite similarity, something that would reappear at the end of the company’s life.

Singles would remain a constant throughout the 1950s for the firm with machines such as the 90cc DP Baby Lilac, 125cc PV Minna scooter and the 104 JF model that looked oddly like the Italian Rumi scooter.

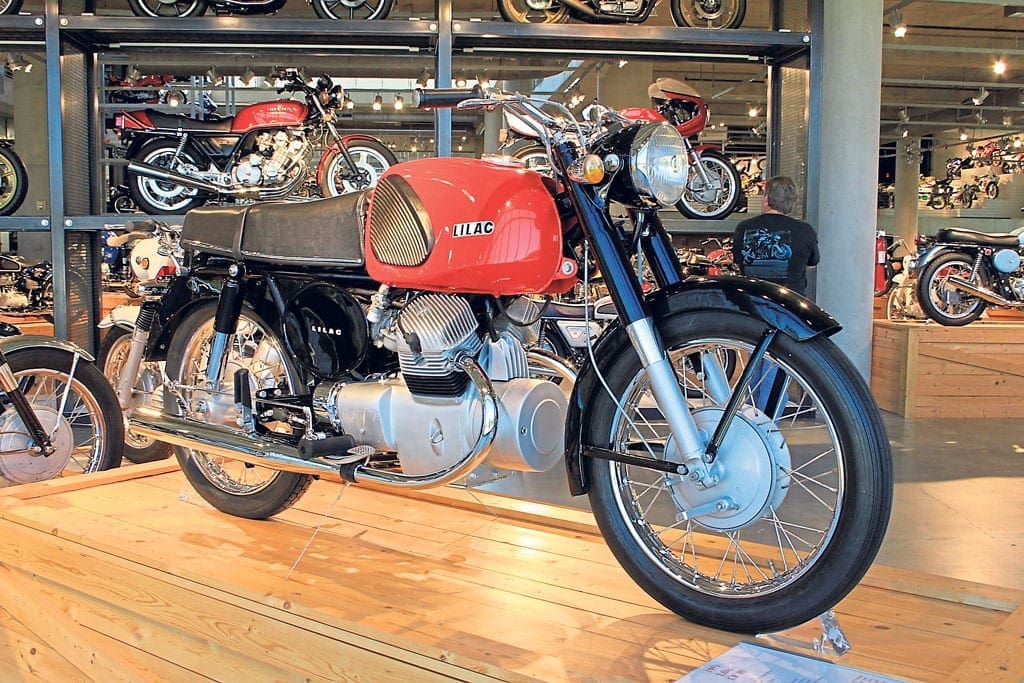

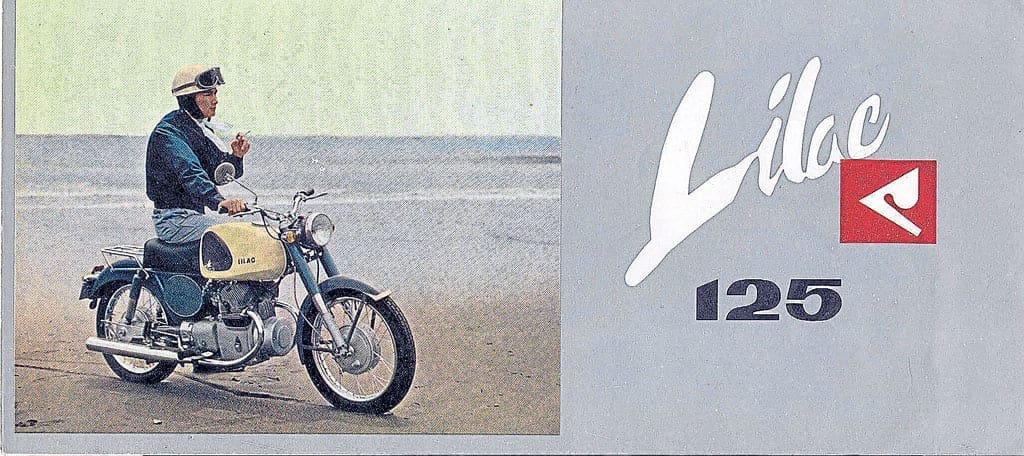

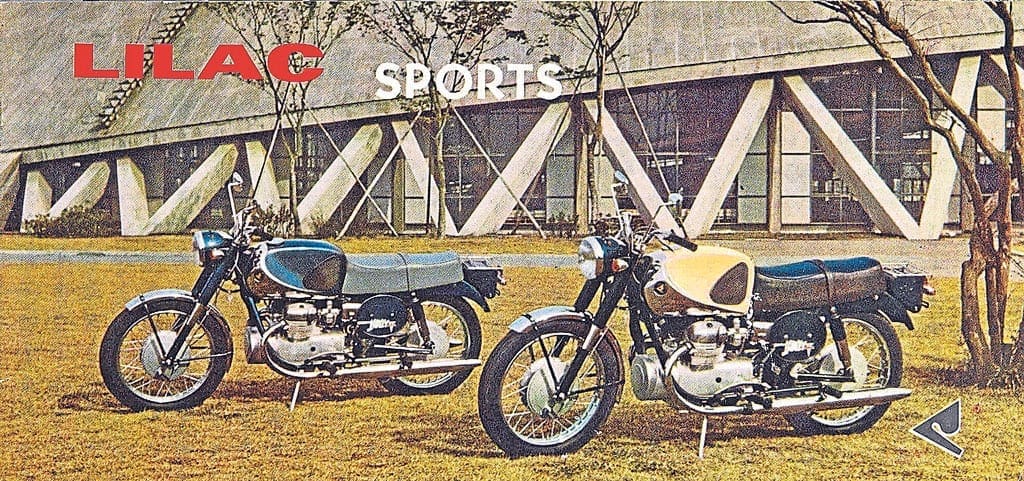

Some of the firm’s most iconic designs and creative thinking appeared in the late 1950s and early 1960s with a range of V-twins that made up the LS, MF, CF and CS series. The engines were mounted transversally across the duplex frames with an included angle of just 66 degrees between the cylinders of Marusho everything other than the 125s, which gave a remarkably narrow front profile. Equipped with telescopic forks and a rear swinging arm, the range encompassed capacities from 125cc up to 300cc, with a nominal 350 existing as a prototype.

The design was reminiscent of the West German Victoria Bergmeister but ran a conventional transmission of gears, not the oddball chain and cogs setup of the European machine. All the V-twins used a rotary four-speed transmission with shift pattern of Neutral-1-2-3-4–Neutral, which was relatively common at the time for the domestic home markets. The 125cc models ran compact 90-degree motors rated at 11.5bhp, which was as good as any four-stroke competitor of the time.

Long before small-block Moto Guzzis or pushrod Honda CX500s, Marusho’s engineering delivered one of the motorcycling world’s most considered all-round packages with a generator at the front of the motor and a shaft final drive. The V-twin range was uniquely styled with many models featuring heavily sculptured tanks that were half chrome-plated and equipped with triangular knee pads.

Dependent upon intended market and/or use, the bikes were either equipped with single carburettors on a Y manifold or twin units mounted direct to the cylinder heads. The final, 250/300, iterations of the V-twins were marketed as ‘Lancer’ models and the name is often erroneously attributed to all the V-twin models.

Despite troubled production, dubious business decisions and dire cash flow issues, Marusho as a company refused to roll over and play dead. The early to mid-1960s saw the firm give one last roll of the dice in a bid to gain significant market share and, crucially, break into the all-important American market.

In 1964 the ST was launched as a 500cc flat twin, remarkably akin to contemporary BMWs. Revised and updated in response to reliability issues, the bike was rebranded as the Magnum for 1966 but, again, failed to garner significant sales in the US.

One final push a year later saw the Marusho Magnum Electra launched with an electric starter said to be from an Italian car and proper oil filtration system but it was all too little, too late. Only 125 examples were built before Masashi Ito, founder of Marusho, had to call it a day but, in all honesty, he and his unique machines had run along for much longer than many had believed possible.

If further proof were needed that Marusho Lilac were innovators extraordinaire you only have to look at the prototype Lilac C-103/C-105 models. Who else would have dared to dream of sports-oriented 125 or 160cc flat twins with a pair of carburettors?