Of The Big Four, it’s arguable that Kawasaki did the most with the least when it comes to early trail bikes. As Steve Cooper explains, while Kawasaki was never the largest or most prodigious of firms in its earliest days of two-wheeler production, it nonetheless had more than a dozen different quasi-mud pluggers under its belt by the mid-1970s.

Most of the machines offered were based around finely engineered disc valve two-stroke singles that reflected the firm’s ancestry of aircraft manufacture. Similar engines with less aggressive porting found themselves powering commuter and general purpose bikes, yet Kawasaki had also made in its name and established its reputation upon antisocial, frantic and ill-handling two-stroke triples so it was a moment of supreme irony that it would be the first firm to distance itself from 2T oil and everything that it represented.

However, the signs were already there in late 1972 if anyone cared to look closely enough – the all-new Z1 900 wasn’t a logical step on from the H2 750, it was an open commitment to a totally different type of technology… with poppet valves.

Enjoy more Old Bike Mart reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

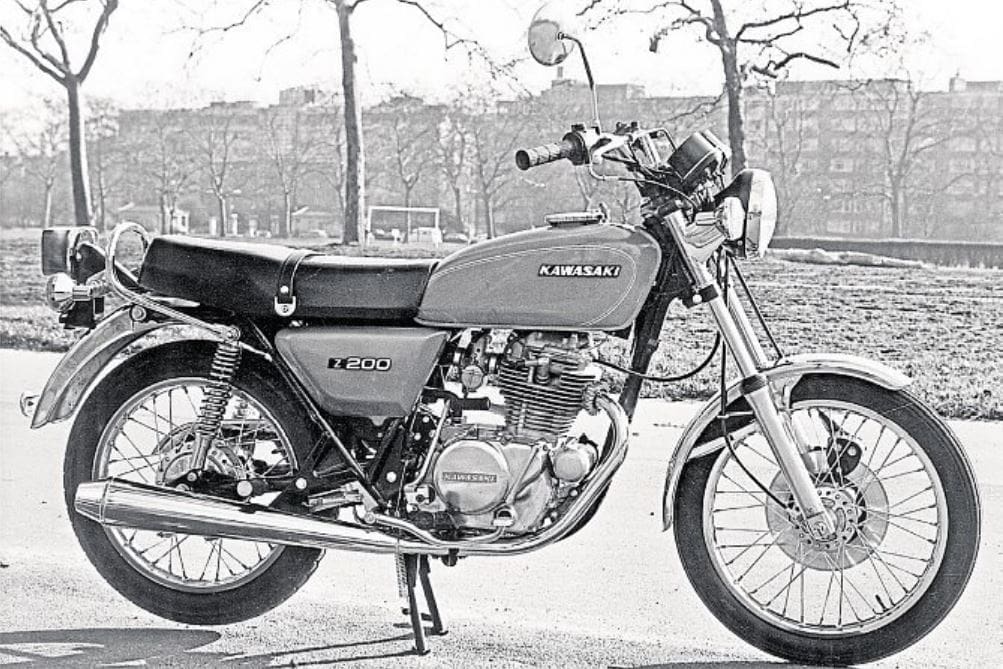

The second to market four-stroke Kawasaki was the infamous Z400 of 1976 which few found either inspiring or reliable, but the firm was on a roll now and committed to a new way… for the moment at least. The 1977 model year saw the launch of a pair of four-stroke singles that were aimed at both learners and commuters. The KL250 was focused on riders who might otherwise be tempted by Honda’s XL250 or were two-stroke averse–Yamaha and Suzuki would both happily take your money with the DT250 and TS250. The Z200 was targeted directly at commuters who wanted honest-to-goodness daily transport. Both bikes featured all-new engines centred around a two-valve overhead cam motor utilising chain drive.

In essence the two motors were very similar, with the Z200 running a 66 x 58mm bore and stroke while the KL250 ran 70 x 64mm. Both motors were effectively off the same drawing board and period journos of the day would imply that the KL was effectively a bored and stroked 200, with both sharing a similar transmission.

The trail bike was relatively well specified and unquestionably well styled. The gauges mimicked the outgoing triples, the rear guard aped the duck’s tail that had become a signature design and the wheelrims were high-end DID alloy. Unfortunately, it all went a little wrong when it came down to the ill-considered exhaust system. Mild steel painted satin black, it was always corrosion prone but its real Achilles heel was its routing under the engine and then twisted around the right-hand rear shock absorber.

In overall terms the bike was okay but in no way a serious threat to the, by then, five-year-old Honda XL250. It was down on power and up on mass.

The Z200 was a no-frills daily rider that, fortunately, ran 12v electrics – unlike the KL, which struggled somewhat with just 6v. Gifted an electric start, the baby Zed was scheduled to be all things to all riders and to a point it managed it… well, almost.

It became rapidly apparent that there was a quality issue with the gear lever or, more particularly, with the splines on the gear change shaft. Used as a regular commuter, there was soon a long line of angry customers awaiting replacement parts and warranty-backed engine rebuilds. Another quirk of the 200 was its strange front brake which was a cable-operated disc. Very much a triumph of ambition over ability, the design rapidly seized in use and the rebuild kits supplied by dealers became infamous in the number of strange parts they contained. Last but not least, the Z200 soon earned a reputation for consuming silencers. Lots of short runs where the unit never reached full temperature allied to a relatively poor build quality soon had owners looking for viable aftermarket alternatives.

And yet such quirks from either machine were nothing when compared to the elephant in the room. Both motors ran their camshafts directly in the alloy cylinder head and, predictably, the reciprocating steel was soon munching its way into its bearing surfaces. That Kawasaki’s prototypes and test bikes hadn’t done this is a given but the sterile environment of product design and testing is often leagues away from the reality of the real world. Infrequent oil changes and the use of inappropriate grades only exacerbated an already parlous situation.

Jock Kerr Motorcycle Developments Limited rapidly became the recognised experts for repairing KL250 and Z200 cylinder heads using a rolling bearing conversion and some serious machining of various parts. Eventually Kawasaki had to acknowledge the problem existed, and later iterations of the motor featured a top end equipped with a roller bearing cam.

The original Z200 lasted just two model years before being substantially revised in 1979 and latterly had its points and coil ignition swapped for CDI. Circa 1980 the bike became the Z250 using the KL250’s motor in revised format. In this guise the bike would run for some eight years as the Z250C along with a factory custom version badged as the Z250G. The KL250 struggled on in mildly updated form into the early 1980s before being dropped with the advent of 125cc learner laws.

Other than the Z1 and Z650, Kawasaki’s first generation of four-strokes met with limited success, prompting the company to return to two-strokes such as the KMX, AR and KDX water-cooled models. It would be the late 1980s before the firm would revisit four-stroke singles with any enthusiasm.