The evocative sight and sound of a Manx Norton thundering along the roads of a small island are the stuff of motorcycle legend, after all, isn’t that how the ‘Manx’ got its name? Except in this case it would be a ‘Jersey’ Norton as the island in question is just off the coast of France rather than mid way between the Ireland and England. Now Jersey isn’t exactly known for its road racing history but there is a thriving trials and hill climb ‘scene.’ It was the latter discipline that Jersey man Graham du Feu was interested in having a go at. Graham already rides a 500cc single but one originating from Selly Oak rather than Bracebridge, he is the organiser of the Port of Jersey backed classic two day trial, so the desire for a classic ohc racer was a bit of a departure from the norm for him. Quite a departure as he admitted to always having had trials bikes and apart from a brief ride on a modern Japanese machine, had never been involved with the roadster scene.

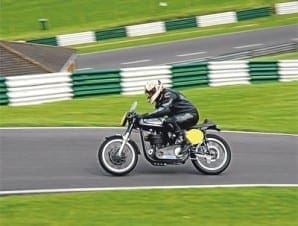

Anyway, fast forward a few months and Graham phoned to say he had got a 1962 30M 500cc Manx Norton. “Wow, great Graham, I’ll have to have a look at it when I’m over for the trial next,” says I. “Why not have a look now, we’re up at Cadwell and Mick Grant is teaching me to ride it.” Too good an opportunity to miss, so to Cadwell I went. Once up there it was soon apparent that rather than just the riding to learn, it was the whole Manx experience that Graham needed and Granty was just the lad to help.

First stages

Graham’s new bike is an ex-Harry Whitehouse machine that Stuart Tonge had been racing. The Norton is eligible for the Lansdowne period race series so isn’t as radical a bike as it could be. Stuart’s a more than capable engineer and the bike was well set up though Graham did say it felt totally alien when he first cast a leg over the saddle. “Not just the riding position but the whole leathers and full face helmet thing too,” he said as he lined up the rear wheel on the starter rollers. It all went a bit noisy then as the engine burst into life and Graham set off to the paddock holding area to await his first run around the track. To my untutored eye he didn’t seem too bad but Mr Grant has more of a critical eye and as we watched from the paddock wall it was obvious he was making mental notes for his post-session chat with Graham.

Learning curve

With pen poised I readied myself for Graham’s return to the paddock. “How did that feel?” asked Mick, when Graham took off his helmet and removed his ear plugs. “Awesome,” grins Graham, “and really confidence inspiring, it felt as if I was leaning right over in the bends yet it didn’t feel as though I was on the edge.” He goes on to say the riding position felt right for him, no need to stretch to the bars or hitch up his knees to get his feet on the footrests. “it’s actually comfortable and a lot less vibration than I expected.” Mick listens then suggests a few ways in which Graham could go faster. “Don’t bother too much about late braking, it’s more important to get the power on as soon as you can than to outbrake the other riders,” he says. “sort out where the apex of the bend is, then once you hit that have the power on and you’ll easily pass the late brakers.” Mick passes on more tips for going quicker and in his next track session Graham showed he’d been paying attention as he was getting close to the limit of the Avon AM22s. At the end of this track session there was more of a chance to talk basics with Graham and find out a bit more about the bike and what it’s doing. “Once it’s warm,” Graham says, “it’ll go to 8000rpm on the Shell V Power pump fuel, though I put octane booster in too just to be safe. I’ve found it revs cleanly all the way up the range and doesn’t bog down if I change up too early.” Graham goes on to say the brakes were, from a trials rider’s point of view, very sharp once they heated up but still safe. “The whole experience is pretty amazing y’know,” he tells me, “I guess it’s good that Mick has experience of all types of bikes and I’ve learnt a lot today from listening to his advice…” he was about to continue when Granty – clad in racing leathers – came over and said “you’ll learn a whole lot more in a few moments when you follow me round the track.” And so it proved as Graham upped the pace lap after lap until the end of the session. It was difficult to say who was most pleased over his improvement – teacher or pupil – as they both had big grins.

The bike

Though Lansdowne eligible machines have to look like they were in the period, there’s room for hidden mods and this particular bike has a five-speed box with a Newby belt primary drive and clutch. It’s running on a Lucas SR magneto, has Morris MLR30 circulating through the oil ways and “… starts easily… usually,” grins Mr du Feu, after pushing the Manx up and down the paddock. The chassis is standard Manx featherbed, though the dampers are Koni rather than Girling and he’s thinking about a lighter oil in the Roadholder forks. “Mick says that will help them come back up faster.” Are you pleased with the bike Graham? “Oh definitely.” Any conclusions from the day? “The gearing will need to be lowered for hill climbing, but by how much will be a matter for experimentation, I’m just pleased to have been given a good grounding on riding the bike and now I can go on and learn more about it.”

Down and dirty

It is true to say most Manx models were used for road racing, either on the short circuits or the real roads courses… most but not all. The odd one or two made their way off the roads and onto the dirt, not as a result of over cooking it on a fast bend but as an intentional decision. Aldershot based scrambler Les Archer lifted the final European MX crown in 1956 using a superbly modified 500cc model that was a little long in the tooth compared to the BSA Goldies of the day. Archer mainly used the early long stroke engine – though in the mid 60s when noted Manx tuner Ray Petty got involved, a dohc unit was tried – however that’s not to say his engine was old and outdated as it had been constantly developed in the light of experience.

For instance after problems with high bore wear the Mahle company in Germany produced a light alloy barrel, devoid of a liner but with a chrome plating direct onto the bore that solved the problem in one fell swoop. With a Standard Manx tipping the scales at 313lb – check this – it wasn’t exactly a heavy machine in roadster terms but to fling one around the MX circuits, less weight would be better. Archer’s team carved, pared and cut as much of the surplus off as they could by waisting and drilling bolts but it remained a big machine. Luckily Les Archer was, and is, a big bloke and the bike suited him with it’s spread of power, carefully chosen gear ratios and pinpoint handling from the special frame based on the Featherbed. The machine is in the National Motorcycle Museum and was the subject of a feature in Classic Dirt Bike issue nine.