Before Royal Enfield’s sensationally-styled Continental GT made its debut, the 250cc Crusader line had already evolved into two variations on a very agreeable five-speed theme – the leading link front fork Super 5 and the sporty-looking Continental. This is how the road testers of the day saw them.

When Royal Enfield launched the unit-construction 250cc Crusader in 1956, followed by the tasty Crusader Sports a couple of years later, the Redditch concern was onto a winner.

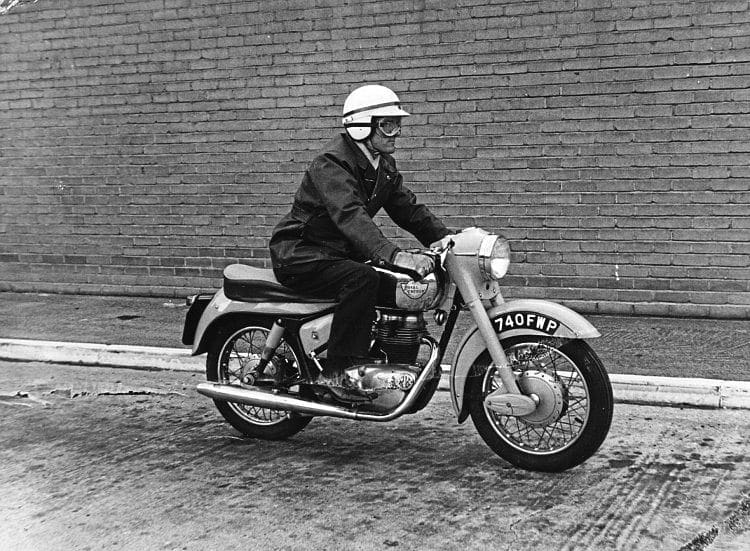

By 1963 a five-speed, close-ratio gearbox had become the icing on the cake as two very different-looking models were launched – the Super Five and the Continental.

In The MotorCycle of July 12, 1962, the tester certainly seemed impressed by the Super 5.

“Had there been a London Show last year,” he wrote, “it’s a pretty safe bet that the Royal Enfield Super Five would have had the crowds fighting to get near it.

“Already the Crusader Sports had built up a strong following among those with an eye for a nifty two-fifty. Now the Crusader unit had been pepped up still more, and there was an entirely new leading-link front fork; but above all a five-speed gear assembly, the first production job of its type in Britain, was incorporated.

“Altogether it was a tempting dish by any standard,” went the report, “but the proof of any dish is in the eating. So now that we’ve had the chance to taste the Super 5, what’s the verdict? Highly digestible!

“It’s a little honey, a truly delightful model, lively as any cricket but with never a trace of harshness in its make-up.

“With a compression ratio as high as 9.75 to 1 and a top-gear ratio of 6.02 to 1, some lumpy running at runabout speeds might have been expected – but the surprise is that the engine is as tractable and docile as that of a typical tourer.

“There’s speed in plenty when you want it, yet also the facility to tonk along in top around the 20mph mark – and even accelerate from there.”

The tester found carburation clean throughout the range, and commented on the fact that, while the use of 17in diameter wheels permitted a seat height of only 29½in, allowing the rider to plant his feet firmly on the ground when at a standstill, the footrests were fairly high set and the centrestand tucked well away to allow the Super 5 to zip into a bend without any odd bits scraping the ground.

Losing count?

“As for the gearbox,” he wrote, “there is the inevitable fatuous question: ‘Don’t you lose count?’ No, of course you don’t; not if you have any soul for the music of a well-tuned engine. You play by ear, and by the motorcyclist’s instinctive feeling for his machine.

“If, for instance, there is a headwind and the model seems happier in fourth than top, then use fourth – it’s as simple as that.

“On a diet of 100-octane fuel (yes, it will run on premium grade, but don’t expect the last ounce of performance) the little Enfield could potter along in town traffic, top gear engaged, with never a hint of protest.

However the engine has a dual personality. Up at the top end of the rpm band there is a surging bonus of power, and to make the most of it the close-ratio box must be used to the full.

“On a clear stretch of highway, it paid to hold third until the upper fifties, and fourth until past the 70 mark on the speedo dial. Then cog up once again and let the needle soar round into the eighties. Glorious!”

In typical 250cc Royal Enfield tradition, however, the speedometer was five or six miles an hour optimistic in the upper reaches.

The Motor Cycle report praised the cush-drive rear hub, long a feature of Royal Enfield products, observing that it really did smooth out the transmission, and the test rider was mightily impressed by the leading-link front fork.

“Navigation is right out of the top drawer,” he wrote, “so much so that, until you peek down to see the leading links bobbing merrily, it is hard to believe that the fork is working.

“Steering lock is somewhat restricted, but that’s a small price to pay for such superb handling.”

The brakes were excellent by the standards of the day, pulling the bike up from 30mph in 30ft, but the fuel consumption was a trifle disappointing at 58mpg overall.

The highest true one-way speed achieved at MIRA was 83mph, and the Super 5 cost £240 10s including purchase tax.

“A two-fifty it may be,” the report concluded, “but the Royal Enfield can give the average five-hundred a run for its money.”

As an aside, when Charlie Deane tried out a Super 5 in the May 1963 issue of Motorcycle, Scooter and Three-Wheeler Mechanics, it was one that had been ‘breathed upon’ by Twickenham’s ace tuner Geoff Monty and, fitted with a sports dolphin fairing, it achieved a top speed of well over 90mph. Strangely, too, the magazine claimed an overall fuel consumption of 74mpg – 16 more than The Motor Cycle’s figure!

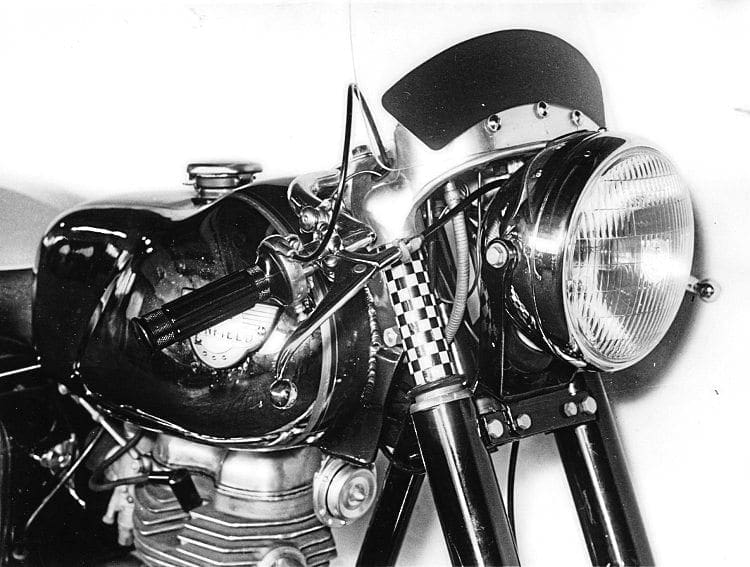

In contrast to the Super 5, the Continerntal was aimed at a different market altogether – the young, sporty riders who wanted above all else to emulate their heroes on the race circuits.

The road test we have chosen comes from the March 6, 1963 issue of Motor Cycling.

“For well under £250,” the report began, “the Enfield Cycle Co markets a traditionally-designed 250 single that has five speeds in the box and can top 80mph – indeed the Continental under test bettered this by several mph.

“For a young man’s market, the Redditch factory has given the motor 20bhp and armed the gearbox with five excellent ratios. The handlebars are of the dummy clip-on type, the tank slimmed for the knees and fitted with a racing filler, and the footrests are as high as they’ll go.”

With an out-and-out sports specification, the Continental differed from its stablemates by including exposed rear unit springs anda racing-type flyscreen, abbreviated chromed mudguards, an air-scooped front brake to combat fade under heavy braking, built-in rev-counter, telescopic front forks instead of leading-link, and altogethera more jazzy decor.

On test it recorded a top speed of 82-83mph without wind assistance, and the report went: “With the rider normally seated, it could be punched regularly to 70-72mph, the best power being produced between 6000 and 7500 rpm.

“The Continental is a logical development of the basic Crusader, itself the first postwar 250 built from scratch and not a rehash of a 1939 design,” continued Motor Cycling’s report.

An overall mpg figure of 72 was recorded, and the oil consumption, at first quite obvious, steadily improved as the miles mounted and the rings bedded in.

So there we have it – two Enfield five-speeders with quite different characters. If any Old Bike Mart readers still own either of these models, we’d be interested to hear of their experiences.

Read more News and Features at www.oldbikemart.co.uk and in the April 2020 issue of Old Bike Mart – on sale now!