Inspiring, viceless and utterly reliable – Honda’s CB500 four made so much more sense than its larger-capacity brethren that those same virtues still hold true today, writes Steve Cooper.

No review of classic 1970s middleweights would be complete without due coverage of the Honda CB500.

Today the bike is overlooked and, amazingly, regularly ignored and even marginalised. To perpetrate any of these actions is near heresy — but why should this be the case?

The reason is as simple as it is obvious. This was one of Japan’s first machines that truly punched above its weight and foretold the cult of the powerful middleweight sports bike.

Thus the Yamaha R6, Kawasaki ZRX600, Suzuki GSX-R 600 and, indeed, Honda’s own CBR600.

All of these machines offer ballistic performance in smaller chassis than their one-litre brethren while bestowing lightning handling in easy-to-use packages.

Even if the performance is light years away from the CB500, the concept remains the same — big power in a smaller motorcycle.

The Honda CB750/4 had stunned the world at its 1969 launch.

Here, apparently was a race bike on the road and one that was capable of riding as far and as fast as the rider was capable. The reality was somewhat different.

The 750 was in a low state of tune and therefore not especially stressed; careful design allied to ultra-high quality control ensured the bike was unlikely to fall apart in short order.

If there was one fault that could be pinned on the world’s first superbike it was its sheer weight and mass. For many potential riders it was simply too unwieldly.

This criticism got back to The Big Aitch fairly quickly and its response was both concise and devastatingly effective. Enter the Honda CB500.

Launched globally in April 1971, the new middleweight shared little of import with its older brother.

The 750’s dry sump lubrication was abandoned in favour of what would soon be the industry-standard wet sump. Despite popular opinion stating the engine oil would be thrashed to hell and back by the transmission, the predicted disasters never happened.

Japan had never been above looking at what other manufactures did, and Morris/BMC had been using a similar set-up in the hugely-successful Mini since 1959.

The top end of the CB500 ran an overhead cam controlled by chain as per the 750, but primary drive was via a Hy-Vo chain for quieter operation.

Physically the machine was significantly smaller and lighter, which made four-cylinder motorcycling substantially more accessible to the masses in terms of size and cost.

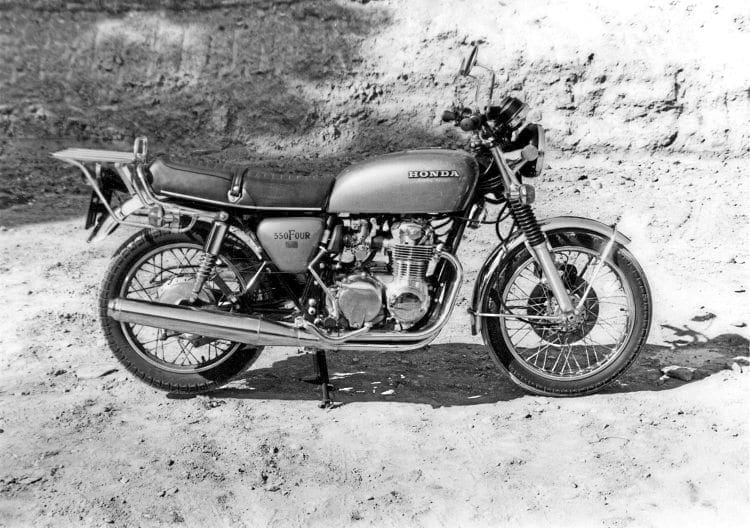

By 1972, Honda had effectively completed the set with the CB350 four, and it wasn’t long before an American motorcycle magazine ran the trio of single- overhead-camshaft, air-cooled fours alongside each other.

The unanimous decision by all concerned was that the CB500 was the pick of the litter. It provided four- cylinder luxury at sensible money with a turn of speed to satisfy all but the hardest rider.

Handling from the half-litre Honda outclassed the bigger bike, while its pulling power and ease of use eclipsed that of the 350.

Today the word ‘compromise’ is generally regarded as something rather less than ideal, but back in the early 1970s, what Honda had achieved was little short of remarkable.

Perhaps the only minor negative was the fact that the 500 needed to be revved hard in order to extract maximum performance, but then again the bike didn’t protest at such use.

This was as close to a racer on the road as you were likely to get in 1971, and as if verification were needed, it’s worth recollecting that Bill Smith won the 1973 Production 500cc TT on a CB500/4 at just over 88 mph, and eight seconds ahead of the second place rider on a Suzuki T500.

Hindsight is a singularly useless gift, but it does make you wonder what might have been if Honda had had the ability to launch both the 750 and 500 at the same time.

The bigger machine enjoyed a profoundly longer life span even if it was well past its sell-by date when it was pensioned off.

By comparison, the 500 was produced for only three years model years (1971-1973) before undergoing a makeover.

One of the few genuine criticisms levelled at the bike was its relative lack of torque, which Honda addressed with an overbore, taking the engine to 544 cc.

This apparently minor change raised torque by 10% and revived the bike’s fortunes massively to the point where it was still going strong as late as 1978 in some markets — and, with major revisions, the basic architecture hung on until 1985 in the guise of the CB650.

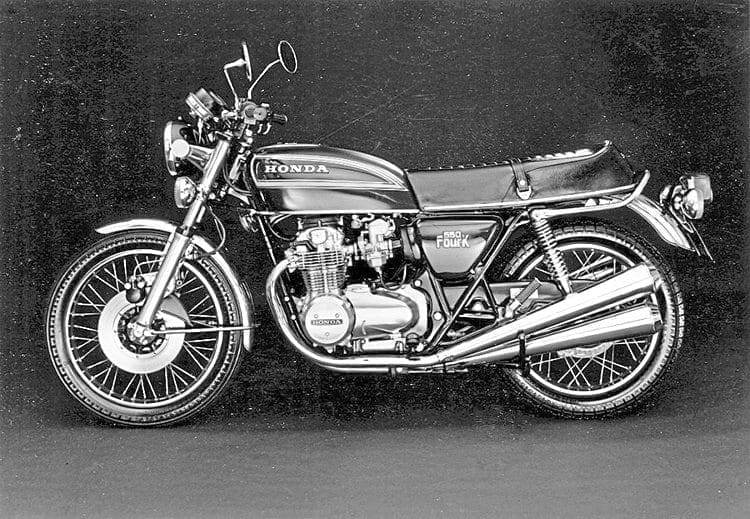

As for styling, the original concept was sold in three guises — the original CB500 with four tulip shaped silencers, the CB500F series with a four-into-one exhaust aping the CB400/4, and finally the CB550K series running four chromed megaphones and reserved conservative paint schemes.

Purists will generally argue the initial 500 is the bike to choose, and its lines are unarguably classic and correct. The F series polarised opinions from the outset, and has continued to do so.

Some argue the bike plagiarises the styling of the seminal 400/4, but does so in a less-than-acceptable manner. Certainly Honda could have made a better fist of getting the correct curves into the exhaust system’s header pipes.

The later CB550 K series, with the megaphone 4-4 exhausts, sold to a generally older clientele who wanted the look of the early 750s but were unable to afford them at the time.

Market values have begun to climb, but as might be expected it’s the earliest four- pipers that make top dollar.

Many CB550Fs were treated as hacks, and few seem to have survived unmolested. Perhaps the best of the lot is the CB550K2 with the iconic tulip exhausts but running the bigger engine. In the Candy Lime Green colour, little of the period comes close.

Clinically assessing a CB500F today, you might genuinely wonder what all the fuss was about back in the day, but if you consider and appraise what was being offered when the bike was released, the picture changes dramatically.

Here is a half-litre motorcycle running an overhead cam, fitted with a disc brake, running four cylinders and four carburettors, an electric start… this is a level of sophistication previously unheard of.

Now fire one up and listen to the refined rustle of that engine. It’s totally unlike anything else of the time. Sit in the sumptuous saddle, snick into gear and pull away.

Instantly the inherent ease of use is evident. Now work the engine and delight in the auditory delights of both the inlet roar and those four exquisitely-styled silencers — pure magic!

Open the throttle and rag the bike towards the nine thousand red line — go on, you won’t break it. And that, my friend, is the miracle of the CB500/4. A desire to rev, a will to perform, an ability to do this and more all day long until you can ride no more.

Cynics argue that Honda made bland, soulless machines. The converts know differently. Bikes such as the world’s first road-going 500cc four are inspiring, viceless, mega-mileage motorcycles. No more needs to be said!

Read more News and Features in the November 2019 issue of Old Bike Mart – on sale now!