Stirred by Old Bike Mart’s request for bike shop memories, Tony Proctor recalls his own early motorcycling days, which grew from mimicking his scrambling heroes.

Emulating the scrambling we watched on TV, my friends and I built ‘dirt track’ bicycles from all sorts of bits and pieces, and spent many an evening charging about in the local spinney or racing along muddy river banks.

We’d build jumps and clear pathways to provide fast trackways, but there would always be some slower parts where balance was more important than speed.

To make things more ‘off-roadish’, we’d strip a bike to the bare frame and wheels, and fit the cut-off tread from a worn-out tyre inside our proper tyres before inserting the inner tubes in a bid to stop punctures from thorns and other sharp objects.

Preferring cable to rod operation, we’d normally fit only one brake – normally the rear for broadsliding – and with no mudguards we’d get seriously plastered in mud.

To prevent trouble at home we’d use the river to wash the bikes and ourselves cleanish, and all this pretend scrambling and trials (and even speedway if the grass was wet) inevitably led to motorcycles replacing the push bikes.

The seed was sown after Doug, a mechanic friend of my father, gave me an old sack of motorcycle parts to play about with.

The council flat we rented had a brick-built, useful-sized shed where I ‘worked on my bikes’, and it was there that I pulled the bits out of the sack, not really understanding that in my hands I had an Ariel crankcase, cylinder barrel, piston and crankshaft, with a gearbox and other parts right at the bottom, and my memory keeps seeing the letters ‘HTT’.

My father told me about a bike that could be bought from a gamekeeper he knew. Two friends and I clubbed together to raise £5, and dad borrowed an Army lorry (long story) to bring home my first motorbike at the ripe old age of 14, a 500cc BSA A7!

We kept it in the alleyway between the council flats because it was too heavy for us to put into the shed. The gamekeeper had used the machine (on road tyres) to chase poachers off the land he protected. The bike had no headlight, but a table tennis bat was screwed in its place (something only the previous owner could explain!).

As we hadn’t reached our full growing potential, the handlebars were far too much of a stretch, and trying to hang on to the A7 was a challenge, so we needed proper bars. I lived in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, and the nearest motorcycle dealer selling any pretence of competition machinery was Val-U Motorcycles in Luton, Bedfordshire.

We rode our dirt bikes to Luton along the main road. This included Offley Hill, a very steep gradient that made even the buses and lorries struggle, so we had to get off and push – quite a scary activity – before coasting down towards Luton and arriving at the shop.

On one side of Val-U Motorcycles’ double-fronted premises a Greeves trials bike, Dot scrambler and road-going BSA sidecar outfit were on display, and at the other was a short counter and doorway though which you could see the workshop and, further on, the back yard.

The place was dark and smelled of oil, rubber and cigarette smoke, but hanging on the wall, suspended by a piece of wire, was the object of our journey – some scrambles-style braced handlebars. Buying them cost every penny we had, but we rode home with the heartening thought that we could tear down Offley Hill and get home much more quickly.

Once the bars were fitted, we couldn’t wait to try the A7 on the plot of undeveloped building land that had become ‘our’ field test track, but after seeing us riding the BSA, an older lad from the old Westmill council estate came over to look at the machine. “I’ll give you £10 for the bike and the bars,” he said, and after a short discussion the deal was done and we’d made a little money. I saved my share and started to think about my next purchase.

A few weeks later a friend’s brother, Ronnie, who was bike mad and rode a BSA C15SS, said he had a mate with a bike to sell, and £7 15s got me a Francis-Barnett something-or-other that had a 197cc Villiers engine and alloy panelling around the air filter and toolbox area that made it look very special.

The front forks were scrawny-looking things with about two inches of travel, but the bike had a 21in front wheel with a trials-pattern tyre and the 18in rear was fitted with a scrambles knobbly – the business in my eyes! It even had a big rear sprocket and a serious off-road-attitude high-level exhaust, but this was a bodge if ever I saw one.

The front pipe had been cut close to the exhaust port, literally reversed and welded back up so that the exhaust could take a 180-degree turn before going into the baffle-less silencer. I rode it on the fields and tracks for some time, but to avoid attracting too much attention I used a round oil can stuffed with wire wool as a makeshift silencer.

One morning, one of our neighbours, Pat, a gas fitter who always had plenty of tools handy, was knocked off his 250cc James Captain by a car, luckily suffering only bruising. The bike was written off, but when he gave it to me I took out the engine and fitted it to my Fanny-B. The front engine mount needed repositioning, and a new exhaust system had to be fitted, both jobs requiring welding skills.

I ordered a new front pipe from Pride & Clarke, and had to pay for it with postal orders. In contrast to today’s ‘order now and we’ll be knocking seven bells out of the front door tomorrow’, it arrived about 10 days later in a British Railways parcels vehicle.

The new pipe was immediately cut into four sections, positioned on the Francis-Barnett rolling chassis by adhesive tape, and the lot was pushed three miles to the premises of a local garage engineer, Burt Wells, who gas-welded the pipe and mounting and gave me some tips on how to mark any future welding areas with adhesive tape. He was an ace welder who proved his alloy gas-welding expertise by welding a central oil tank for another lad, Spout.

You always had to be on the look-out for the near-silent police LE Velocettes, whose two-way radios made more noise than the bikes, and it didn’t take long to fall foul of the law. The LEs were used off-road (it must have taken nerves of steel!) for keeping an eye on the farm buildings, and in the end there were so many of us ‘schoolboys’ racing around on the common, in the spinney, along farm tracks and fields that the police had to get involved.

Foolishly, one Saturday morning we rode along an access track to the Lister Hospital where a policeman on an LE caught one of us who, in his haste to turn around and roar away on his 98cc Moto Guzzi, fell off and was caught. He gave all our names and addresses, which culminated in five young schoolboys in court receiving fines and endorsements to licences we were too young to hold!

To keep me out of any further bother with the boys in blue, my father made arrangements with a landowner in Meppershall, a Mr Haley, to not only let me make a discreet track in the field next to his cottage, but also keep the Francis-Barnett in his double garage, provided I didn’t scare any cows in the field next door.

After leaving school at almost 16 and starting a garage apprenticeship, I soon realised that, even in the 1960s, cycling to work and back along main roads with poor lights could be downright dangerous, so I started looking for a suitable motorcycle. Dad and I visited the Earls Court Motorcycle Show in 1967, and with me being all for the off-road stuff, we met Frank Hipkin of Sprite Motorcycles and ordered a kit-form 250cc Sprite Trials with a Villiers 37A engine, telescopic forks and a red glass fibre tank for about £167 10s.

I soon realised, though, that trials bikes were not the ideal form of road transport unless you lived very close to home, and it was time to think about something else.

Hitchin had two motorcycle dealers, Morgan’s and Jimmy Lane’s. At Morgan’s I part-exchanged the Sprite for a Honda Benly 125, which was much more suited to road work. It was fitted with Dunstall reverse-cone megaphone silencers which made the little engine sound fantastic.

Morgan’s was the proverbial dark, dingy open-fronted shop with a workshop on the side, complete with a petrol pump that swung out over the pavement. The deal was more of a straight swap, as no cash changed hands, and as soon as I had the logbook I went round to the previous owner’s house to check on the Benly’s history.

I used it for a time and passed my bike test on it, and the only fault I can remember was a blown fuse – not bad for six months’ hard use! Now, though, armed with my motorcycle licence, I waded through Motor Cycle News, Motor Cycling and Motor Cycle Mechanics in search of my next bike.

Jimmy Lane’s was across the town almost next to the Hermitage cinema, and the shop front was very posh and well-kept, with no peeling paint or gaudy signs. Jimmy always shut up shop for two weeks when the Isle of Man races were on, and took some of his staff with him, so if you wanted anything, you had to wait until they came back.

One Saturday afternoon after work, I found myself sitting at one side of Jimmy’s uncluttered desk while he sat on the other puffing a cigar. “Honda Benly 125 with three owners and you want hire purchase,” he said. “OK, it’s a deal!” I was about to become the proud owner of what was, in 1968, one of the best bikes to own – a T120 Triumph Bonneville, registration KAR 83G.

The Bonnie duly arrived at my parents’ home a few weeks later, not in a van but strapped inside the enormous box sidecar of a 500cc Triumph combination. Three or four days later, the engine went down on one cylinder (the workshop foreman’s explanation was that the advance/retard mechanism had seized). About a week after that, the oil pressure relief valve cap cracked, leaking oil everywhere, so back it went and they fixed it again.

The Bonnie ended up in a serious accident at Corey’s Mill roundabout, near Stevenage, when a driver cut the corner and my right footrest was forced into his left front wheel arch, flipping me and the Bonnie into the path of an oncoming Hillman Imp. I spent some weeks in hospital and more time at home convalescing.

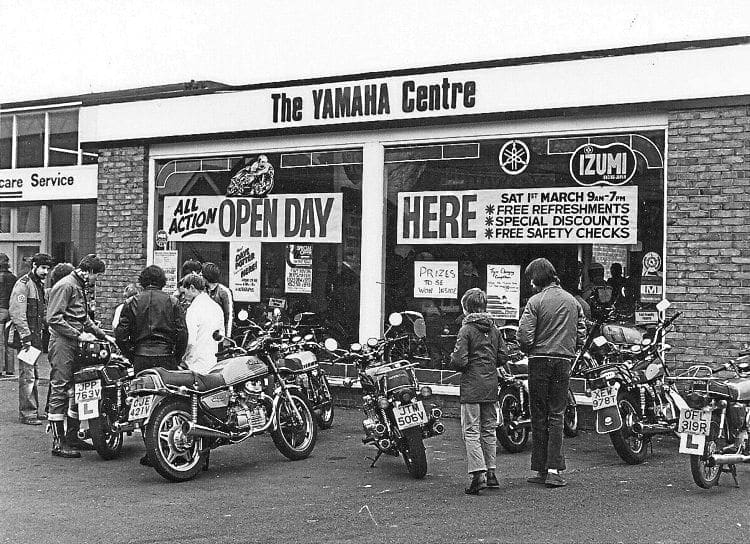

Although the Bonnie was rebuilt by Lane’s, I sold it to a bike trader and vowed never to ride again – but a few years later I’d bought a 1972 ex-Comerford’s 325cc Bultaco Sherpa, and by 1978 I was the manager of a Yamaha Centre in St Neot’s – but all that can wait until next time!

Read more News and Features at www.oldbikemart.co.uk and in the April 2020 issue of Old Bike Mart – on sale now!