Pete Kelly turns to the Mortons Motorcycle Archive once again to see how the reporters of the day saw three entirely different kinds of motorcycles named after famous race circuits.

Just one look at the new Triumph Daytona 765 triple – or the Thruxton R on page 22 – suggests razor-sharp handling, searing acceleration and stoppers that those who remember the twin-cylinder Daytona of just over 50 years ago could only have dreamed about.

Naming road-going motorcycles after famous race circuits is nothing new, of course, but the launch of the new Triumph got me looking through the Mortons Motorcycle Archive to learn what the late David Dixon of Motor Cycle and, eight years later, John Nutting of the same title, thought about the original 490cc parallel twin Daytona, the 844cc Moto Guzzi Le Mans, and the 350cc Ducati Monza.

Both were superb riders, and some years earlier Dublin-born David, whose famous shamrock helmet is still fondly remembered, had even been allowed to ride a 250cc Honda four racer (if I remember correctly, the headline read something like: “Light the blue touch paper…”).

John, one of the finest guys I ever had the privilege of working with during my three-year editorship of Motor Cycle in the mid-1970s, went one better as far as racing machines were concerned, with a memorable scoop test ride on one of the original fearsome two-stroke, four-cylinder 750cc Yamahas!

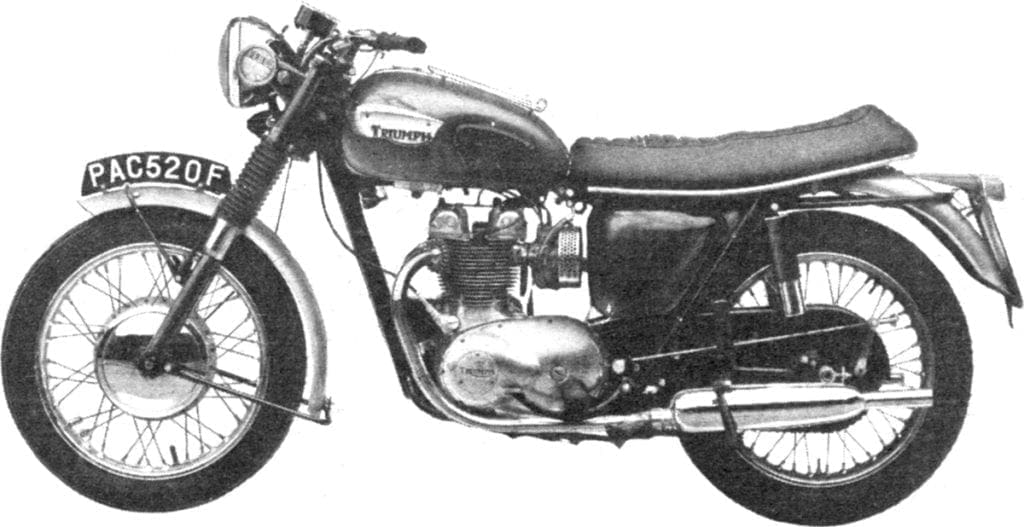

Trad Twin – Daytona

The 490cc T100T TriumphDaytona road test began: “Our tastes are often fickle. Way back, the five-hundred twin reigned supreme in the larger-capacity classes. Then the demand was for bigger cylinders and the six-fifty became more popular; now the seven-fifty is on the up-and-up.

“Yet many owners would find that a top-rate five-hundred such as the Triumph Daytona, a super-sports roadster with twin carburettors, would provide all the performance they can use. In addition, it would offer advantages of saving in purchase price and running costs, and in handleability.”

Indeed the Daytona, which replaced the T100SS, was so named because of Triumph’s winning performances at the famous Florida race track in 1966, and again in 1967.

With a mean top speed of 104mph and a very presentable acceleration curve, on give-and-take roads the Daytona was up with the best six-fifties, but whereas the bigger bikes gave more bottom-end power, the Daytona needed higher revs, and more frequent gear-changing, to give of its best.

The Daytona’s gearing was lowish, and its four gear ratios closely spaced, to provide optimum acceleration, and at the unrestricted MIRA proving ground, the machine proved capable of an effortless 80mph cruising gait, with ample power in reserve to exceed 90mph.

Before the first start of the day, the clutch required unsticking by sharply depressing the kickstart with the handlebar lever in, but the starting itself was easy. Just close the air lever, lightly flood both Amal Concentric carburettors (the outward-facing ticklers were easily accessible) and one prod would do the trick, hot or cold.

The test rider found the riding position a good compromise for riders of widely varying builds, with the relationship between the footrests, handlebar and seat providing a slight forward lean to both combat air pressure and remain comfortable at town speeds. The rear of the petrol tank was sensibly narrow for knee grip, and the positioning of hand and foot controls were ideal, but the twist grip, even though well-greased and the cable well-oiled, was slightly heavy in operation.

“Wide, well-padded and with cross ribs to prevent the rider from sliding around, the seat was a boon and proved completely comfortable on day trips in excess of 350 miles,” wrote the tester, but the Daytona’s greatest asset was its sheer manoeuvrability.

“Feeling no heavier than some two-fifties, it could be ridden zestfully yet safely,” the report continued. “The light, sensitive steering was reassuringly positive on fast main-road bends, and the steering damper seemed quite superfluous. Slick cornering was encouraged, as the bike could be leaned well over without fear of anything grounding.”

Much of the test mileage was on wet roads, so the Daytona had ample opportunity to show any vices, but the reporter was happy to conclude: “It had none.”

For a bike with such sporting potential, its suspension both front and rear was on the firm side, but while the well-damped front fork was an excellent example of its type, working smoothly on all surfaces and with no suggestion of clashing on even the sharpest of bumps, the rear units were perhaps a little too hard.

“Though set at minimum pre-load, they failed to iron out major road shocks,” the reporter observed, “and for riders of average weight, perhaps the comfort level would be improved by lower-poundage springs.”

The light-to-operate 8in-diameter front and 7in-diameter rear drum brakes, with floating shoes and finger adjusters, performed well, providing powerful retardation from top speeds yet remaining ideally controllable on wet city streets.

When applied really fiercely in crash stops at MIRA, the front brake squealed the tyre on the emery-like surface without locking the front wheel, and during prolonged riding on rain-soaked roads, neither brake suffered from water on the linings.

Motorcycles of the day were rarely brilliant (excuse the pun) when it came to lighting, and I know from experience how difficult it always seemed to be to write positively about the lights and – even more so – the horns of the era.

On lighting, the Triumph Daytona seemed much better than average, and the road tester wrote: “Main-beam lighting was good enough to allow daytime speeds after dark, and the dip-beam prevented dazzle. A worthwhile detail is the use of a three-position toggle switch on top of the headlamp shell, which proved easier to operate than rotary-type switches,” but the comment about the horn was entirely predictable – “Totally inadequate for the performance of the machine!”

Lubrication of the rear chain was set by means of a valve inside the oil-tank filler neck, and after adjustment, the system worked well (in normal use, the chain required re-setting at 500-mile intervals).

Unlike the “superb” description that was usually applied to the tool rolls of Japanese machines, the Daytona’s tool roll was described as “of good-quality and adequate for routine maintenance.”

Finished in an attractive combination of green and matt silver, with the usual parts chromium-plated, the Daytona was what it looked – a highly developed, purposeful, practical sportster for the enthusiast.

The MIRA performance charts showed speeds through the gears at a maximum-power 8000rpm to be 42, 63, 84 and 103mph – not bad by any means for a 500cc roadster of half a century ago – and a standing-start quarter-mile covered in 15.5 seconds with a terminal speed of 88mph.

The best mean maximum speed, achieved with a 13-stone rider wearing one-piece racing leathers, was 104mph, and the best one-way speed, with a moderate following wind, 107mph.

The best braking distance from 30mph to rest on dry Tarmac was 28ft 6in, and the minimum non-snatch speed in top was 23mph.

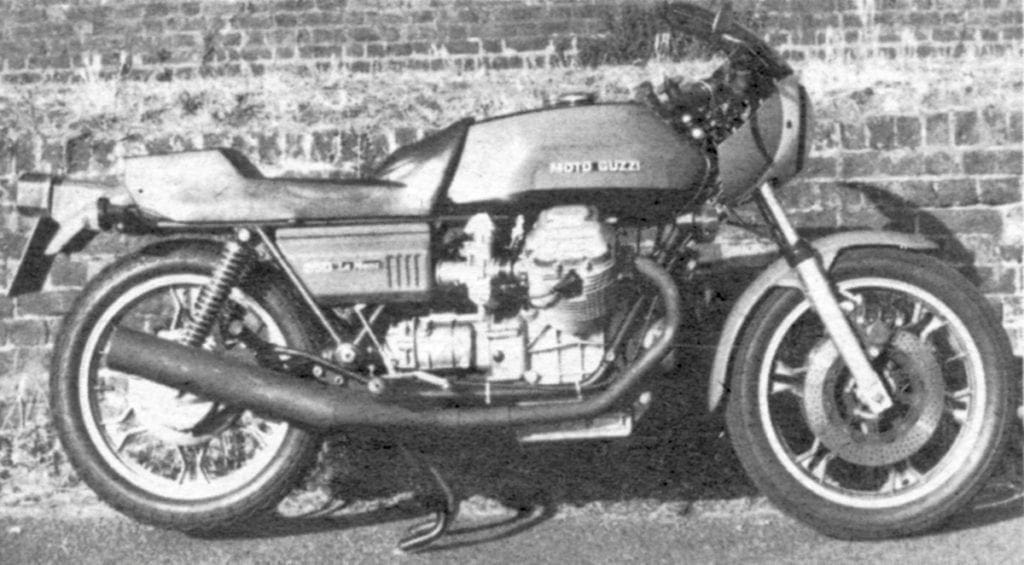

Talking Italian – Le Mans

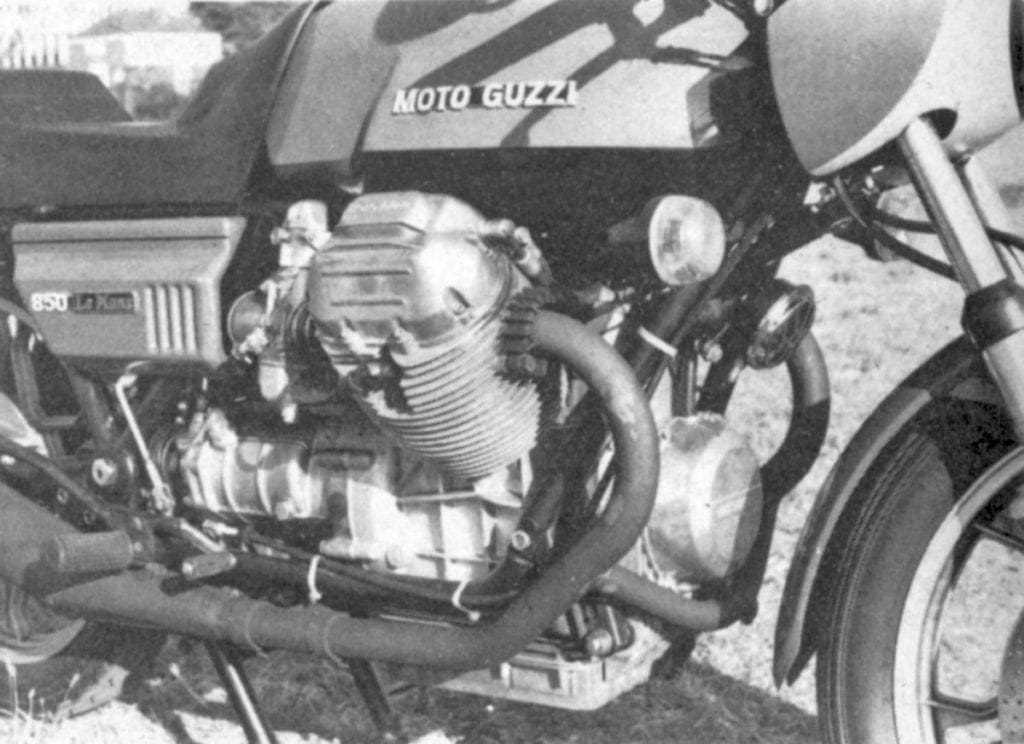

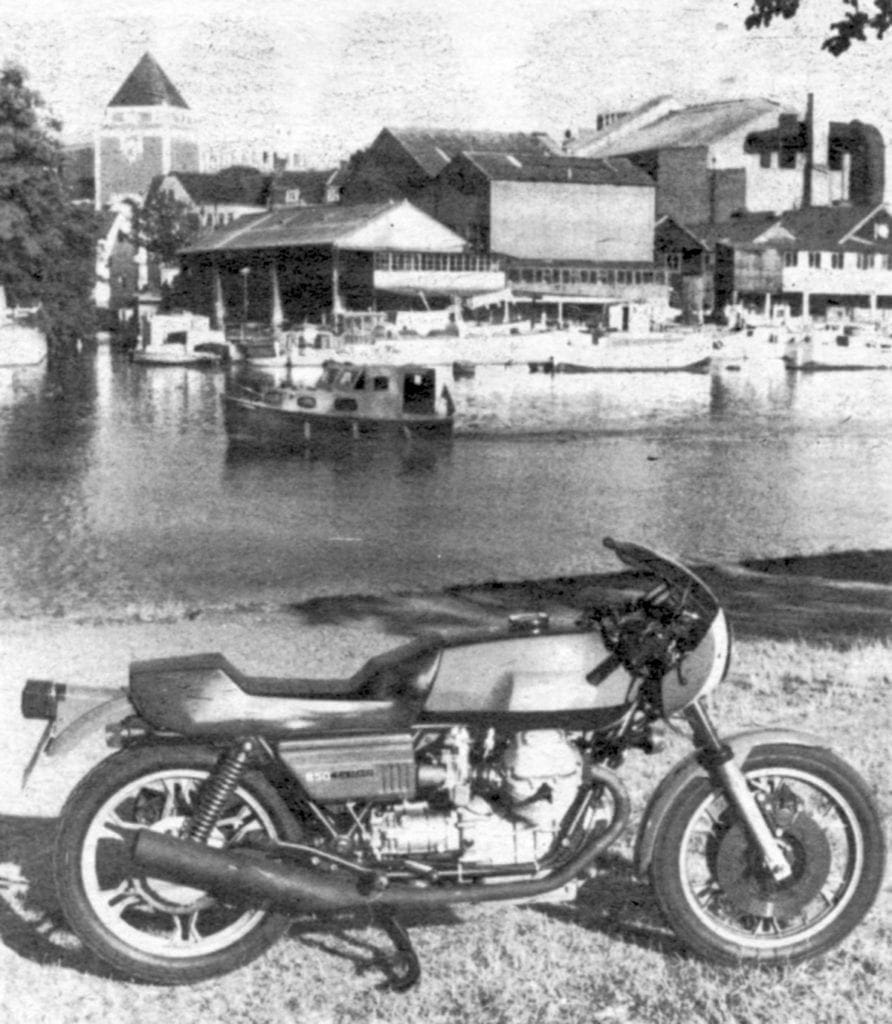

I don’t know who first coined the word ‘superbike’ – I suspect it was Motor Cycle News – but eight years after Motor Cycle’s road-test of the Triumph Daytona the so-called superbike age was well and truly with us, and John Nutting found himself putting the £2000 top bike of the Moto Guzzi range – the legendary 844cc V-twin Le Mans – through its paces.

First manufactured in 1976, and named after the 24-hour endurance race at the famous French circuit, the Le Mans was developed from a V7 prototype that was unveiled late in 1972, and during its 16-year production span, the engine capacity grew from 850cc to 1000cc.

You could always rely on John to come up with an imaginative storyline, and I cannot resist re-playing his introduction of 43 years ago: “Fancy yourself as a fly killer? Well, you can forget those sprays. Just grab yourself a big, bad Moto Guzzi and blast off.

“After just a few high-speed heatwave miles, the Guzzi’s little dayglow fairing had picked up enough debris that it was almost unrecognisable – and then the trouble started, for that fairing had proved to be a godsend, though not for its deflective qualities.

“The Le Mans is so fearfully quick that drivers needed ultra-quick reactions to keep out of its path – and that fairing was just as effective as a headlamp for spreading those crawlers. Not when it was plastered, though.”

That was the flies sorted, then! However, as John rightly pointed out, the Le Mans was more than just a fly-catcher, and given free rein, the big V-twin would gallop deceptively to almost 130mph and handle true as a die to that speed as well.

“It’s a thoroughbred Italian sports machine with race-bred suspension, braking and that classic feel born of the Italians’ enthusiasm for building truly exotic equipment,” John continued. “At two grand, you might imagine the Le Mans is a luxury motorcycle as much as a sportster, and enhancing that luxury look is a pair of the new FPS cast-alloy wheels made by a company in the same group as Brembo, which makes the disc brakes used on all the big Guzzis with the unique compensating system.

“So too is the clever styling. This boils down to the neat moulded foam seat that stretches over the rear of the massive fuel tank and the classic Italian red paint finish.”

Sadly, though, those looks faded with use, and no sooner had the tank been filled for the first time than the cap leaked and promptly peeled off the tank lining. It got worse, for after a short two-up spin the seat, which is unsupported where it covers the rear of the tank, split open in two places.

And there was more: it proved impossible to adjust the preload on the long rear suspension units without removing the two matt black silencers, and closer scrutiny of the detail work revealed a clutch cable cover melting where it touched the exhaust pipe, and it was the same with one of the throttle cables where it touched the cylinder.

Back then, Italian speedometers were notoriously vague, so when the speedo cable finally broke – well, what did it matter really?

The way John put it was: “When you’re ambling down the motorway at an indicated 90mph and 850 Minis whizz past like you’re standing still, you begin to doubt the instruments and realise why Moto Guzzis have acquired such a reputation for monster performance. Getting 140mph on the clock is no problem at all, but bears no connection to reality.”

Back in the day, we thought the way to spell the instruments’ maker, Veglia, was ‘Vaguelia’, and the tester wrote: “Why they should be so inaccurate on a machine of this cost is crazy, particularly as they can be so far out (about 16mph) as to be illegal.”

Despite all this, that first Le Mans really was a performance machine, with the true ability to cruise at well over 110mph – just right for keeping cool in the 90-degree heat that was experienced during the testing.

Gearing was spot-on, with the bike revving to the 7300rpm maximum in top with the rider flat on the tank to achieve a two-way mean speed of over 123mph.

As for the handling, the frame and home-brewed suspension made the Le Mans one of the best-handling machines that Motor Cycle had tested, with a low centre of gravity and superb steering geometry that made it equally suitable for sensitive control at low speeds and “train-like rigidity combined with manoeuvrability at three-figure speeds.”

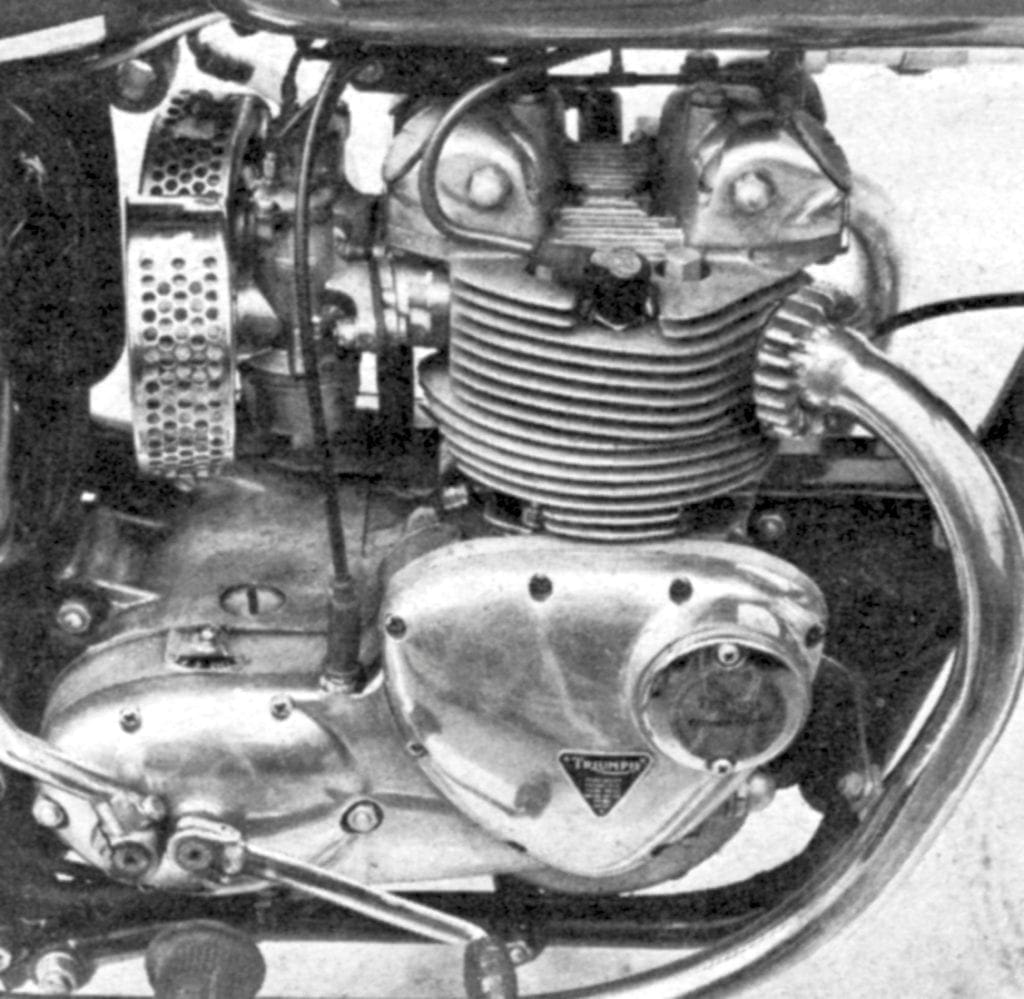

The road tester loved the rhythmical and pleasantly soothing rocking from side to side at low revs, as well as the Guzzi’s unique sound. No air filters were used, and gunning the bike at low revs produced a thrilling roar from the twin 36mm Dell’ Orto carburettors.

The engine is in a fairly high state of tune, with a compression ratio of 10.2 to 1, and with the fairly lumpy cams, the Le Mans didn’t really come on song until beyond 4000rpm. The engine was smooth apart from a slight high-frequency shaking on the handlebars.

“The massive flywheel calms the power strokes at low revs, but does result in the need for patience in gear-changing,” wrote John.

“The car-type, five-speed gearbox has straight-cut instead of helical gears, whines more and is inherently slow in changing, and a definite pause is needed, particularly in the lower gears.”

As for the handling, the frame and home-brewed suspension made the Le Mans one of the best-handling machines that Motor Cycle had tested, with a low centre of gravity and superb steering geometry that made it equally suitable for sensitive control at low speeds and “train-like rigidity combined with manoeuvrability at three-figure speeds.”

Stopping distances with the 11¾in-diameter, hydraulically operated perforated Brembo cast-iron discs at the front and 9 ½in-diameter rear (the foot pedal controlled the front left and rear brake together, with load-limiting on the rear) might have been improved had the standard Pirelli tyres been used, but the test machine had non-standard tyres – a ribbed Metzeler front and Avon rear.

The power of the front stoppers was more than the worn front tyre could really handle, so the best stopping distance from 30mph was a below-par 30ft 4in – not even as good as the Triumph Daytona’s 28ft 6in on drums!

Speeds in the gears at maximum-power revs were 47mph in first, 68mph in second, 89mph in third, 107mph in fourth and 125mph in top.

Fuel consumption was fairly heavy at an average of 39.6mpg on four-star fuel, and a best figure of 43mpg. Oil consumption, too, was quite high at 350 miles per pint.

The tester’s final words were: “Hopefully next year, Moto Guzzi’s production engineers will be able to tie up the loose ends created by the stylists – but I can only say that even by the time my own 1000cc Mk. 4 Le Mans came out, they hadn’t – and reducing the diameter of the front wheel to suit the fashion fads of the day only served to make that long wheelbase even longer!”

The price of the 1976 844cc Moto Guzzi Le Mans was £1999, and for comparison, the Ducati 860 GTS cost £1499, the Norton 850 Mk III £1020, the BMW R90/S £2189 and the Kawasaki Z900 £1369.

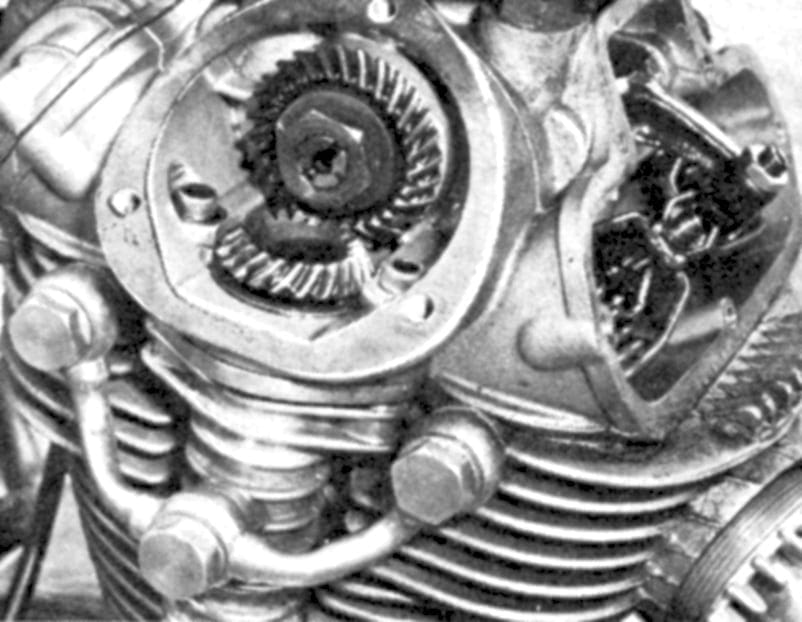

RIGHT: Drive to the single overhead-camshaft was by shaft with helical bevel gears, and the valves were of the hairpin type.

Small Talk – Monza

When pulling out these old Motor Cycle road tests, we thought it might be a good idea to recall one of the small Ducatis named after a race circuit – the 249cc overhead-camshaft Monza – but unlike the fine-looking originals that had shown such great promise in endurance racing, the weekly newspaper chose a later restyled example fitted bizarrely with American-style upswept handlebars that did nothing for its looks, or even its performance!

If it had been mine (and I did once own and restore an example of the Monza’s bigger brother, the three-fifty Sebring, yet another machine named after a race track!) those ape-hangers would have been whipped off straight away to make it look like a proper lightweight Ducati again.

The road test reporter began his appraisal: “Bearing the name of Italy’s most famous race circuit and hailing from a country where small four-stroke singles are very much in vogue, the 249cc Ducati Monza offers, especially, a brisk performance, excellent handling and a miserly thirst for fuel.

“It is a touring model and, like others in the range imported by Bill Hannah in Liverpool, is equipped with an American-style high handlebar. Basically, though, the robust overhead-camshaft power unit is similar to that fitted to the high-performance Ducati two-fifties that are widely respected for their showing in endurance races and similar events.”

As expected, the engine started easily even in freezing conditions and gave plenty of punch right through the range. Pulling away in the rather high (15.8:1) first gear was smooth and slick, thanks in no small measure to a first-rate, light-to-operate clutch.

The five ratios, especially fourth and top, were closely spaced and chosen ideally for the engine’s characteristics, engaging so easily that at times the clutch seemed unnecessary.

The only point at issue was that, although the gear pedal had a short, positive travel, it was mounted slightly too high to operate without taking the foot off the rest.

As for performance, the writer observed: “Though by no means a fast machine, the Monza is tireless. It would cruise effortlessly and, it seemed, indefinitely, at only a few mph below its maximum speed, and with fourth gear so close to top, it was easier to counter slight headwinds and gradients than with the average two-fifty.”

The silencer was nothing like as noisy as might have been expected, keeping the decibel level down at all speeds, and surprisingly the reporter found the chunky, narrow dual seat comfortable rather than hard, but it was in the handling, suspension and braking that the little Ducati really shone, being light in heavy traffic and rock-steady at speed irrespective of road surfaces.

The suspension was well damped and both drum brakes (7in-diameter front and 6 ½-diameter rear) were light and progressive, giving a good stopping distance of 30ft from 30mph in complete safety.

At MIRA, the Monza in high-bar form achieved a mean top speed of 71mph with an 11½-stone rider wearing a two-piece trials suit, and a highest one-way speed of just 72mph.

In 1968 the Monza cost £275 17s including purchase tax.