Today the name of Cecil – or CT – Ashby is unknown to most, but John Milton takes a look at the man who could have been a contender.

[Images: Mortons Archive]

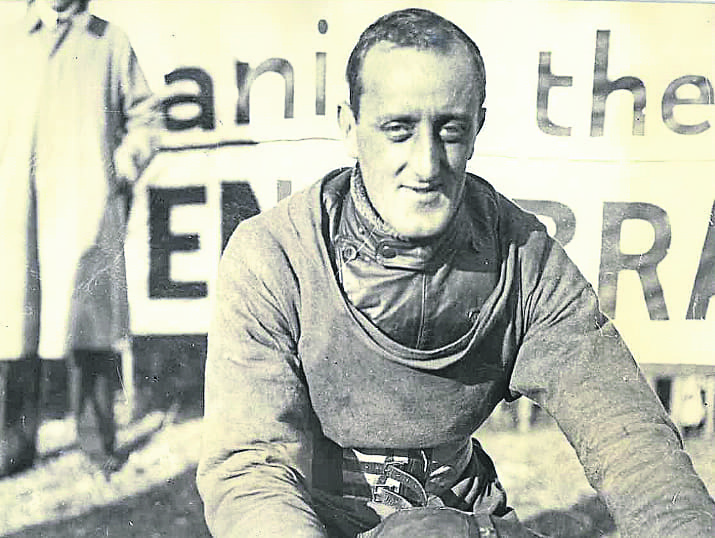

Cecil Thomas Ashby was born in Stoke Newington in 1896, the son of a commercial clerk, and was educated at Grays College in Essex. His background rather decreed that he would follow in his father’s footsteps and live a worthy if somewhat humdrum life. But, for Cecil and thousands of his contemporaries, the expectations of that existence were shattered by one thing: the First World War.

Enjoy more Old Bike Mart reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

While it was among the most appalling four years of the 20th century, wartime did give young men a number of new experiences and, at least in the early months, enlisting was just about the most exciting thing a youth could do. Some 1,342,647 people joined up in the first six months of the war – almost three-quarters of a million in the first eight weeks alone – and that was just the numbers who joined the army. Young Ashby, his education completed, had his eyes set on higher things and he joined the Royal Flying Corps. At first, he was employed as an aircraft mechanic in the transport division but, after two years, he transferred to the flying division and took part in what he termed many “cloud scraps”, first as an observer and later as a pilot. This was in 1917 when the life expectancy of a new pilot in the RFC was often less than two weeks.

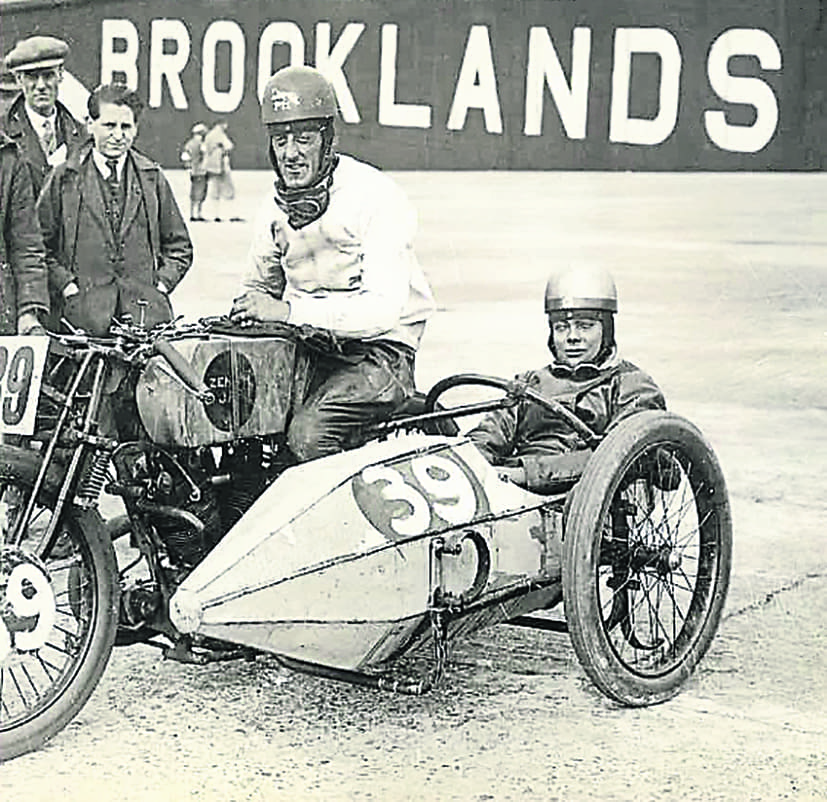

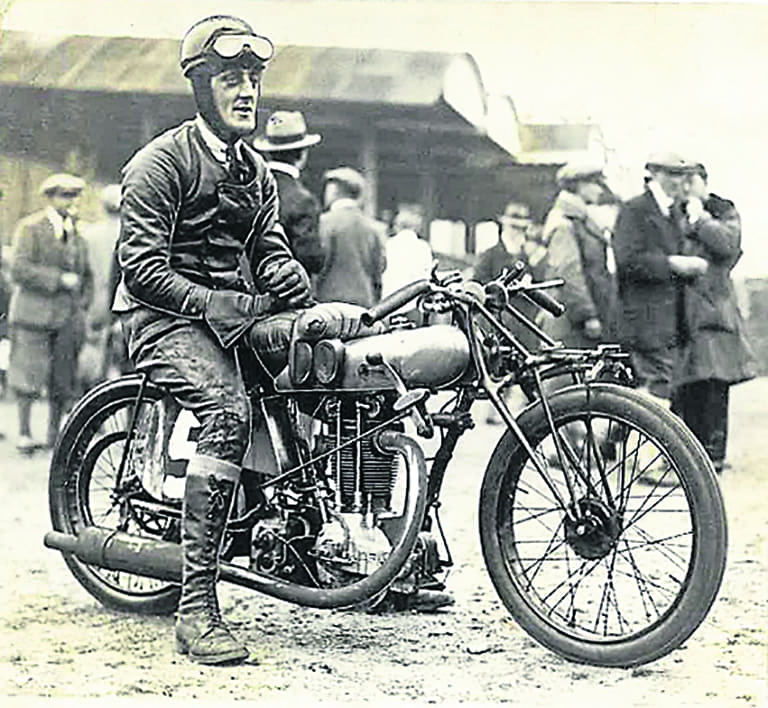

But, despite a few crashes, Cecil survived virtually unscathed to return to civilian life where he took up a position as an import and export merchant in the City of London. Now, note that no mention has been made thus far of motorcycles. Young Ashby wasn’t a dispatch rider during the war, nor did he, as far as can be ascertained, have any interest in motorcycles. In fact, when he purchased an Indian and sidecar in 1921 it was purely as a means of getting around. But he must have enjoyed riding the combination for he soon went on to buy a Rudge Multi and then a 500cc NUT. It was on the latter machine that he first competed in a competition, taking part in the Surbiton Club’s Sopwith Club Trial in 1922. He then entered the NUT in a race meeting although the day ended sooner than expected with a seized engine due to Cecil’s inexperience with operating the oil pump.

The ‘Flying Banana’ really flies

But he was clearly bitten by the two-wheeled bug. He set about equipping himself with more technical knowledge and then joined the Wooler Engineering Company as its new sales manager. Naturally, it would be cynical to surmise that the 26-year-old Ashby only joined said firm because it might give him a chance to ride motorcycles and, after all, the flat twin-engined Woolers were not race machines. That’s what the handicappers at a November 1923 meeting at Brooklands had naturally assumed, for, when Cecil entered one of the company’s machines – possibly to barely disguised sniggers and guffaws – they based their calculations on a lap speed of around 55mph for the Wooler (and there would have been those who considered that generous).

Everyone was astounded when, aboard one of the ‘Flying Bananas’, Cecil Ashby managed a lap of 67mph – from a standing start. Alas, the Wooler then stopped working, as sadly they were wont to do, contributing to the demise of the company by 1930, although it appears that Cecil actually left Wooler shortly after that Brooklands meet. He joined Coventry Eagle as the company’s southern sales and competition representative, a position which allowed him to take part in many reliability trials to showcase the firm’s 500cc sidevalve JAP-engined machine. On this model he won a number of medals but his stay at Coventry Eagle was as brief as his tenure at Wooler had been.

The beginning of 1924 found him taking up a similar position with WJ Montgomery and it was on a Montgomery that he first took part in the TT, campaigning a 350cc racer in the Junior TT. He finished in fourth place, despite breaking all his valve springs. In spite of his relative lack of experience and success, Cecil persuaded Bert le Vack, then competition manager at JAP, to build him a new 500cc overhead valve engine using one cylinder from the new JAP KTOR V-twin which was fitted in the 350cc Montgomery chassis and which won him the 1924 BMCRC racing championship.

“The big twin cure for nerves”

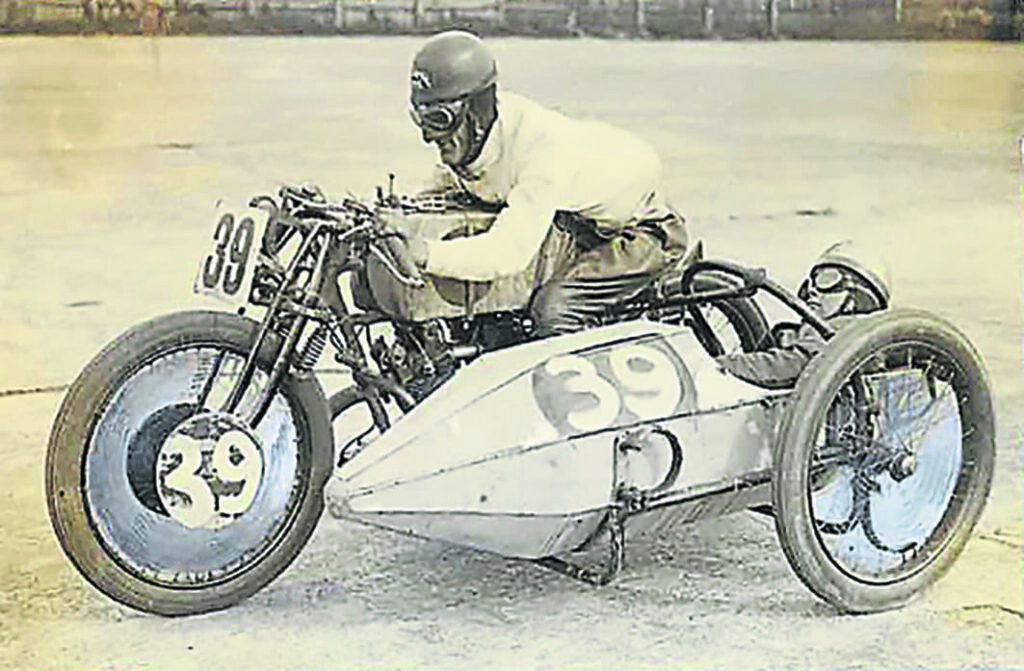

But, while he had enjoyed success with Montgomery, Cecil moved employers yet again, joining Phelon & Moore at the end of 1924 to cover trade sales in London and competition business throughout the south. He would stay with P&M for three years, helped perhaps by the contract he had negotiated which allowed him to ride his own private machines as well as race a P&M. The ink was barely dry on that agreement when he bought a Zenith 976cc, one of the fastest motorcycles in the world at the time. In an interview with Motor Sport magazine in 1926, he declared that he was a great believer in “the big twin cure for nerves”, stating that his theory was that “if one is used to holding a machine capable of over 100mph, by contrast the 500cc machine used for road racing feels ridiculously easy to manage.” He also added in that interview that he was sorry to see the Isle of Man TT course being gradually straightened out for “in its twisty form it provides a far finer test of man and machine than any racetrack.” Those would be prophetic words.

Cecil was successful with P&M, winning a number of trials, an ISDT Gold Medal and collecting podium Grands Prix finishes, while winning the 250cc race at the first German Grand Prix on a Zenith. But in 1927 and newly married to Florence, he left P&M for OK Supreme, perhaps in search of the TT win that had, till this point, evaded him (it would appear that he had stipulated the same clause in his contract that allowed him to campaign other makes). That year he placed third in the Lightweight TT, although he did win the 250cc FICM European Championship, a title he would take again in 1928. It seemed that it would be only a matter of time before Cecil Ashby, now 32 and riding better than he had ever done, would win his first TT victory.

Perhaps the 1929 Junior TT would be the race, perhaps his New Imperial would claim that so far elusive crown…

It was not to be. During the Junior TT he crashed heavily at Ballacraine, sustaining massive head injuries. Cecil Ashby, First World War fighter pilot, Brooklands Gold Star holder, a man for whom motorcycles held no fear, died that evening.

The machines that Cecil rode

Cecil Ashby must have been either very persuasive or such a good salesman that he could dictate the terms of his employment contract (or possibly both) for, as has been mentioned, he managed to convince Phelon & Moore to allow him to compete on machines produced by other manufacturers, no small feat at a time when most marques relied upon competition results and speed records to publicise their products and generate sales. But throughout his relatively short racing career, Cecil rode a number of the leading makes of the day and we take a look at half a dozen of those names.

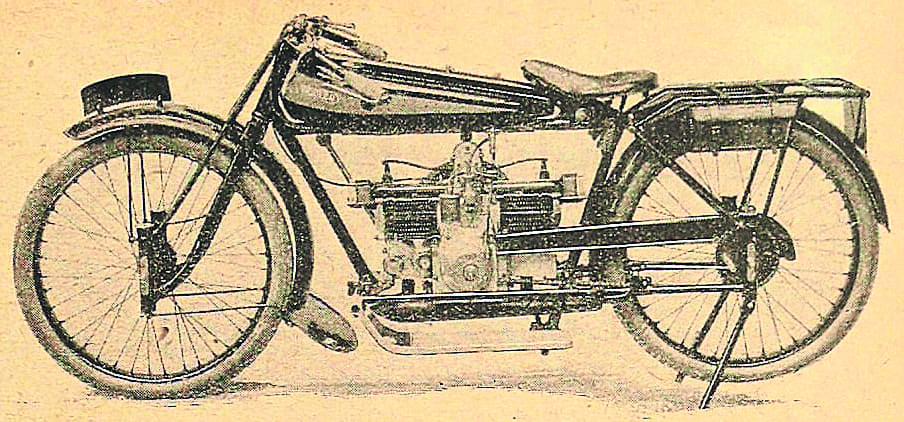

NUT

Although his 500cc NUT V-twin was not Cecil’s first motorcycle, it appears to be the first that he raced. It seems quite likely that this would have been a 1914 model; NUT only made a 500cc twin before the war. The NUT Engine and Cycle Co had been started in 1911 by Hugh Mason and the first NUT motorcycle rolled out of the factory on St Thomas Street in Newcastle in 1912. Just a year later Hugh Mason won the Junior TT on the Isle of Man on a NUT (despite having crashed and broken his jaw a few days earlier), cementing its reputation as a real racer. Whether Cecil chose the NUT because of its pre-war racing heritage is unknown, but it would be the machine which kindled in him a love for going fast on two wheels.

WOOLER

Throughout its life – or should we say lives, for this is a name that would rise again, Phoenix-like – Wooler was markedly unconventional, even during the early days of motorcycling when innovations were commonplace. The company was founded by John Wooler in Alperton, Middlesex, in 1911, and the first model was a 223cc two-stroke which was actually manufactured by the Wilkinson Sword factory. That was followed by a 344cc machine which was recorded as capable of 311 miles on a single gallon of petrol. Motorcycle production resumed in 1919, although by 1920 the company had been re-formed as The Wooler Motor Cycle Company (1919) Ltd. A Wooler was entered in the 1921 Junior TT where Graham Walker, father of legendary commentator Murray, instantly nicknamed it the ‘Flying Banana’, a name that would stick forever. If the young Ashby was besotted by the idea of motorcycles and speed, then Wooler was perhaps not the company for him. Despite his remarkable achievement at Brooklands, it seems that he wished to move to a company whose machines would make him more competitive on the track. As Wooler did not close its doors until 1930 – by which time that would, sadly, have been of no consequence to Cecil – it appears that his move to Coventry Eagle was based upon the lure of that company’s motorcycles. Wooler would re-emerge in 1945 with the first of two radical engine designs, of which we will hear more in a future A-Z of British Motorcycles.

COVENTRY-EAGLE

At the time that Cecil Ashby joined Coventry-Eagle it was at the peak of its success. Having started as a bicycle manufacturer in 1890 and later diversified into motorcycles, the launch of the Flying Eight in 1923 cemented the company’s growing reputation as a luxury manufacturer in such rarified company as Brough Superior (only a Brough was dearer than a Flying Eight). Later it featured a JAP/KTOR 980cc overhead-valve ‘racing twin’ engine – the same motor that Cecil persuaded Bert le Vack to modify for a Montgomery chassis – making it a successful racing machine. That’s why it’s all the more puzzling why Cecil barely had time to lay his pens out on his desk before he left Coventry-Eagle’s employ. Although this was an exciting time in the early fledgling industry where people often moved between companies, the fact that Cecil worked for four companies within little more than 18 months is highly intriguing.

MONTGOMERY

With precision planning (it’s almost like we do this on purpose!), you can find a concise history of Montgomery on page 40 of this issue, but it’s clear that Cecil was fond of the company’s machines, even if his work history with Montgomery was impressively short – although possibly not quite as brief as that with Coventry Eagle. A 350cc Montgomery would give him a fourth place in the Junior TT in 1924, while he clearly had a sufficiently cordial working relationship with JAP’s Bert le Vack in order to persuade le Vack to build him that special engine which would be used in Montgomery’s TT Replica model in 1925.

P&M

While we perhaps today associate Phelon & Moore with the big plodding single cylinder slopers that hauled thousands of sidecars, P&M had been a competitive marque from its earliest days. In 1913, P&Ms took part in the very first International Six Days Trial and entered three machines in the following year’s event. It provided the Women’s Royal Air Force and the Royal Flying Corps with motorcycles during the First World War (and, after the war, contracts to the Royal Armoured Corps to provide outfits). In 1924, the company unveiled the Panther TT Entrant which immediately proved itself in competition and was entered in the TT of that year; it was also the first machine to be called a Panther, although the company was still known as Phelon & Moore during Cecil’s employment. But, while the P&M machines were quick, they were dogged by reliability problems and it may be because of this that, after three years – the longest Cecil would stay with one company – he left for OK Supreme.

ZENITH

Cecil’s own Zenith Championship 976cc was the machine that he rode when not required to campaign the motorcycles of whichever company employed him at the time. It’s not difficult to see why Cecil chose to purchase this machine. From its earliest days Zenith had lived up to its name. Zenith’s chief engineer Fred ‘Freddie’ Barnes patented his Gradua Gear system in 1907 which gave riders such an advantage in hillclimbs that some clubs banned Zeniths from their events – Zenith seized on the publicity and added the word ‘BARRED’ to its trademark. In the 1920s, Freddie Barnes became fanatical about competition Zeniths and soon racing Zeniths held more Brooklands Gold Stars than any other marque. Joseph S Wright, the factory works rider, held the lap record at Brooklands from 1925 to 1935, as well as setting the motorcycle world speed record in 1928 and 1929. As well as Cecil, noted riders of the era such as ‘Ted’ Baragwanath and Bert le Vack (who was responsible for one of those world speed records) competed on Zeniths.