As the eco movement gains more credence and applies pressure to the motorsports world perhaps there is room for change.

Words: Tim Britton Archive pics: Mortons Archive

The archive at Mortons is a vast repository of incredible motorcycling history – from the dawn of motorised transport, when it was all new and no idea was deemed unworthy of exploration, to the more modern times when it seemed everything had been tried.

A trip through the boxes and files in the archive reveals all manner of weird and wonderful things from those days when the inventive world had shown there were other ways of producing transport which didn’t rely on either human or animal power or shovelling coal into a furnace to heat water.

Carl Benz’s early experiments with the hitherto discarded by-products of oil production culminated in a single cylinder two-stroke engine bursting into life in 1879.

From these modest beginnings he developed and patented what would be the world’s first petrol engine vehicle in 1885 and set the world on the road to owning personal automotive transport. It wasn’t long before such engines were adapted for use in bicycles and the birth of the motorcycle happened.

Since those far-off days just about everything else had been tried as a power source for motorcycles – from sail to steam and even jet propulsion – and in the early days it seemed no idea was too outlandish. The problem such ideas had was they were not as convenient as petrol, the substance was already being produced as a by-product of kerosene distilling and was discarded as being of little or no use until Benz showed otherwise.

Even though the poisonous nature of exhaust fumes from petrol engines was known about very early in their life, it was glibly dismissed as being unimportant as they just blew away. While not exactly compatible with today’s environmental concerns over emissions, it was less of a problem when petrol-powered vehicles were few and very far between.

What can’t be ignored is the mistaken belief the world was fresh and healthy before the invention of the petrol engine. There were environmental concerns over pollution and gasses in the atmosphere long before today’s environmental lobby decided to tell everyone about the nasty pollution in the atmosphere… at the tail end of the Victorian era, for instance, the concerns were piles of horse sh… errr… ‘organic fertiliser’ piling up in major cities. There are even scientific studies where scientists have proved the air still contains pollutants thrown out by fledgling industry in the middle of the 1700s.

So, pollution isn’t a new thing nor is the clamour for something to be done about it. The demands have been growing at a rapid rate as vehicle ownership rocketed and the combination of too many vehicles trying to operate on a road system in towns produced stationary vehicles which in turn produced clouds of poisonous gasses. Then, along came this new idea…in the same way gas lights and coal fires were ousted by electricity, the idea of powering vehicles by this wonder took off so… cue lights, bangs, flashes, drum-rolls and trumpeting as the world goes electric!

First though an apology to the new generation – though they may not be reading such a magazine as this – who have the light of the zealot in their eyes and are determined to tell us of this new idea… sorry, not new at all and in fact it didn’t take very long nor was it difficult to find in the archive references to working electrically powered vehicles. Perhaps this should be ‘battery powered’ vehicles, as arguably all petrol engines are electrically powered through their ignition systems.

Within a space of 20minutes or so the pictures accompanying this piece were sourced from the folders, files and boxes within the archive and they show the idea of creating a motorcycle around a battery has been around a long time.

Without very much effort the earliest report I could find of such a vehicle was printed in The MotorCycle of 1919; there may be earlier instances and I’d be more surprised to find there weren’t than to find there were. From this early example, while looking for something else – about North East Centre trials in case you were wondering – up popped a feature circa 1927 questioning why there were so few electric-powered vehicles when one had just successfully ascended Porlock Hill in Somerset. A brief side-track here, in those far off days when road surfaces were poor and vehicles were more basic there were a number of hills around the country which, if successfully climbed by a vehicle, would mark out this vehicle as exceptional; Porlock Hill in Somerset was one.

The description of the vehicle and its line drawing perhaps went some way to explaining why there were so few vehicles of the type in use. Basically the vehicle was a battery with wheels and weighed around 600lb or 272-and-a-bit kg, with an acceleration which suggested it may be quicker to wait for the continental drift to bring your destination closer.

Fast forward a few years to 1946 when Europe was still in turmoil after the war and petrol for private use was in short supply. Alternatives had to be found and such was the surge in electric vehicles the chancellor of the exchequer decreed they would be taxed at the same rate as autocycles and motorcycles under 150cc, thus gaining important revenue for the country at 17/6d a pop… or a whopping 88p in new money.

Around this time The MotorCycle learned of an exciting development in Belgium and reported on such in April 1946. Manufactured by Socovel – SOciété pour l’étude et la COnstruction de Vehicules ELectriques – this electric motorcycle was a genuine production machine already into four figures. In the same way a petrol vehicle has differed little in the basics since its conception (wheel at either end, engine in the middle) so the Socovel was remarkably modern in make-up as it had a wheel at either end, and a battery to store power and drive a small electric motor to provide forward motion.

It did impress the magazine staff of the day and they did a comprehensive test of the machine, praising its qualities and didn’t hide its faults. The big thing they suggested in its favour was ease and simplicity of use with the added advantage of next to no noise. The downside was an incredible weight of 400lb and a non-stop distance of 27 miles. They did find switching the motor off and leaving it for 15 minutes would revive the battery to gain an extra half mile.

Their next angle was to pose the question of how much those 27 miles cost to travel, and they reasoned the electric motorcycle would be more popular to those who might look at an autocycle rather than a motorcycle.

There were a lot of words written on the cost of charging balanced against the lack of need to buy lubrication and they reckoned the battery pack would cost 5d (2p) and the distance per penny was five miles. An autocycle would be 4d for the same five miles but had other advantages which made it more viable. So it seemed the electric motorcycle was to be a novelty and further developments seemed to bear the novelty aspect out.

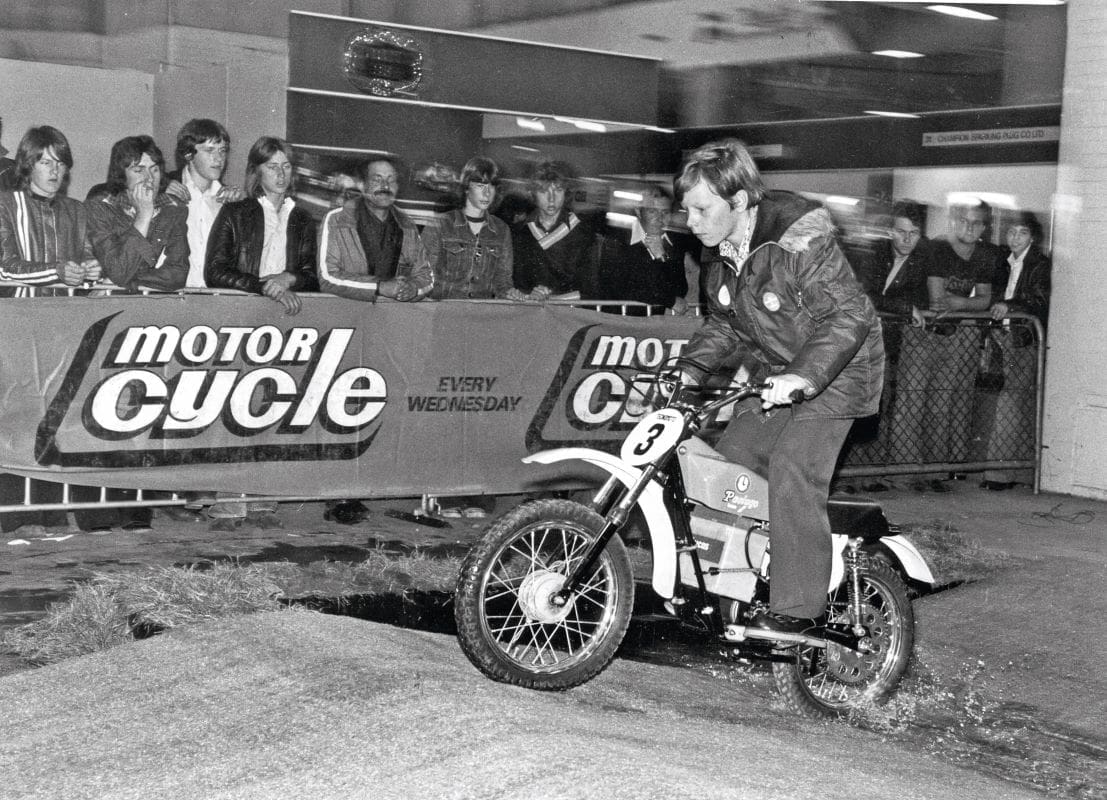

There will be people reading this who will remember the motorcycle shows of the Sixties and Seventies when the idea of running a trials section as a visitor attraction required a non-polluting motorcycle to be made.

Filtrate Oils stepped up to the mark to fund it, Lucas provided the motive power in the form of a wagon battery and the drive was by a SIBA starter motor. A BSA C15T and Francis-Barnett Trials 85 were two machines so converted and the attraction proved popular with showgoers and celebrities.

There was nothing too taxing about the section created, nor was it over-long, but it provided an interesting glimpse into a possible future. What it did do was introduce showgoers to the sport of trials; okay, as it was at a motorcycle show then it is possible the public would already know what a trial was but not every motorcyclist would have been to one. It also provided a clean, dry and quiet opportunity to try the sport and there were always long queues waiting to try their hand at feet-up.

Having seen the display myself at Earls Court in the Seventies I seem to recall the machine doing a few runs then having to be charged, but it served its purpose. I don’t recall the demo after the Seventies but the idea of electric trials bikes didn’t go away.

One of the big problems electric bikes of any sort have is battery life. The ones mentioned so far had limited speed and limited distance capacity, and the more of one attribute meant the lack of the other – basically go faster for shorter distance or longer distance at a slower speed. The batteries of the day were not really up to the job of driving the bike.

To digress a little, those in the construction industry and who are my age or close may recall the early experiments with battery screwdrivers and drills – they’d be able to put a few screws in and then be on charge for almost a day… ‘they’ll never replace our spiral ratchet screwdrivers’… Oh we were wrong, there was a need so battery power tools were improved to the point where they had the durability. No doubt as the need increases then battery development for electric bikes will improve to the point where they will be light years ahead of the old ones. They will become smaller, lighter and have the capacity combined with output which older batteries can only look on with envy.

Modern view

Looking at the older pics with this feature, it is clear the concept of the electric motorcycle has been around for almost as long as the petrol one. Although this is a classic magazine we do acknowledge the modern world, and when CDB was invited to a test day with the latest Electric Motion bikes at Inch Perfect in Lancashire it was an opportunity not to be missed.

Though having ridden electric trials bikes in the past – indeed Electric Motion provided a test bike for the International Dirt Bike show one year – the newer generation of bikes have clutches and as such are ridden in the same way as petrol bikes. There are some differences of course –there’s no noise for a start – but a bigger bonus is no choking clouds of exhaust fumes as you sit in a section queue and you get an opportunity to talk to the rider next to you.

We’ve all heard the jokes about electric bikes as someone thinks they’re the first one to come out with “how long’s the cable with it?” or “do you carry some U2s as reserve?” and there are many more along those lines. There are more sensible concerns though, and the current generation of machines are addressing these and several of the people on the open day were riding their own electric bikes and provided and interesting insight into ownership of them.

The first two quotes came from a long time electric bike owner who went electric from petrol and admitted he’d had reservations and has heard all of the jokes. From his point of view he can go practising and not be regarded as a hooligan, in fact non-motorcycling people approach the electric bike with interest rather than revulsion. Perhaps this is because the world is used to electric-assisted bicycles so the leap from them to an electric motorcycle isn’t too great, whereas learning to go petrol is whole new ball game. I asked my fellow rider if he’d had any problems with his bike, and the answer was few and minor. The modern trials world requires riders to have a lanyard cut-out switch on the handlebar in case a rider and machine part company. A faulty switch kept shorting out but the switch could have been fitted to any make of machine, be it petrol or electric, in the same way a puncture can happen to any machine.

My other concern was distance between charges, and knowing the EM UK team had used its bikes in the SSDT this seemed to bear out the fact the batteries would last the distance. Yes, there were grumbles of “well, they changed batteries…” but the battery is just the fuel source and no one expects a petrol bike to do the SSDT on the tankful in at scrutineering. The charge in the battery will last easily between fuel stops and the battery swap takes seconds. So, concerns addressed I set out to ride the latest EM Trials bike.

It is slightly different in operation to a petrol machine in as much as blipping the throttle will send you into the rider in front, and it took a section or two to adjust my riding for this. On the EM there are three settings for power and these correspond to a 125, 250 and 300cc machine – I kept to the 125 setting and found it would do everything required for me. Once I’d settled in to the riding style and got used to the lack of gears, the whole experience was very enjoyable and to be honest from the classic rider point of view it was harder to come to terms with having brakes than it was for any other aspect of this modern machine.

I perhaps can’t convert you, but I do suggest you take an opportunity to try an electric machine. As lots of people use electric-assisted bicycles it stands to reason a few will convert towards the idea of trials riding and this can only be good for the sport… now in true CDB style, are any of those Sixties demo bikes in a shed somewhere…?